Article begins

I arrived for the second data analysis session with my research collaborator Henry Cabrera, with me carrying two cups of hot coffee, dressed in my signature jeans, sweatshirt, flip-flops, and face mask. Henry was already sitting at our usual concrete bench neatly dressed in pressed slacks and a button-down tailored shirt, listening to morning meditation chimes on his iPhone. He outclassed me. That day, the parking lot beside a usually secluded section of Balboa Park was filled with police, fire, lifeguard, and park ranger vehicles and personnel: the municipal gym behind us had been turned into a vaccination site for first responders.

Henry and I shared a conspiratorial smile over our masks as I set the coffee down and returned to my car for my camera and tripod. Our mismatched attire, the video camera recording our conversation, and Henry’s wire frame “granny cart” with his clothing, art supplies, and bedding neatly folded inside confounded the first responders who walked past our bench. Most people returned my polite “Good morning.” Ten yards away, one officer leaned against his car, arms crossed, casting a menacing stare in our direction. Perhaps we disturbed his perceptions of what homelessness is supposed to look like. We were living the very data we were analyzing.

Whose story is being told by whom?

The events of the summer of 2020 turned American social, academic, and media attention toward narratives of identity and the institutional harms created by the entrenched, colonized perspectives that oversee our political, educational, and financial systems. Meanwhile, the ubiquity of digital visual tools has generated a proliferation of visual storytelling and participatory methods. Methodologies like photovoice, for example, facilitate participants’ photographing significant areas in their lives for reflection and democratic engagement within their community. But engaging in responsible anthropology requires a clear-eyed assessment of how anthropologists use visual research methods. At this intersection of visual modalities and truth-telling through stories is the question, Whose story is being told by whom and to what end?

The growing acceptance among anthropologists, ethnographers, and sociologists for employing visual tools requires constant reflection on researcher/photographer positionality. Such reflection raises essential questions about the control and validity of information, the language used, and what medium is appropriate for producing the narrative.

Henry and I felt the best way to have complex homeless issues elevated to the level of public and policy discourse was to create a visual critical negotiated narrative, what visual sociologist Luc Pauwells calls a “shared anthropology,” using visual methods. Henry self-describes as a “senior, gay, Latino, chronically homeless man.” He has a felony conviction, which means Henry does not qualify for federally funded housing assistance. The last 23 years of my 40-year career as a visual journalist includes closely documenting San Diego’s homeless community. Many local homeless individuals call me regularly to let me know how they are doing. I created a website, www.talesofthestreet.com, where people could relate their narratives of homelessness in their own way. While my familiarity with, and acceptance in, the homeless community gives me a certain knowledge base, I am not currently homeless. Rather than repeat the inherent power dynamic of researcher over the observed “Other,” we sought to generate an impactful scholarly project involving the expertise of researchers and the unique knowledge of field representatives (Henry) woven into a “well-balanced combination of etic and emic views [that] may prove much more valuable than either on its own.”

Storytelling as activism

Our goal was to share Henry’s complex story with a purposefully selected audience of service providers and policymakers who have the power to change policies that obstruct access to resources and make daily life difficult for the homeless. Responsible fieldwork, Pauwels argues, needs to “benefit those who are subjected to it,” by improving the quality of life for the entire community. To that end, anthropologist Sarah Pink posits combining social anthropology with the tenets of design thinking. She envisions coproduced visual documentaries serving as “cultural brokerage” in leveraging influence with policymakers and civic and business leaders.

The cultural brokerage Henry and I produced was a 14-minute video documentary. Henry identified issues of concern in his life and those of his close associates. I then interviewed Henry on camera so his narrative could serve to make those issues and concerns explicit for the audience. I also filmed scenes that reflected the circumstances Henry described. The footage showed him sleeping on a freeway bridge, gathering cans from trash bins, checking in with friends at their clandestine campsites, accessing food and a shower, using his insulin, and hiding his belongings for the day. One scene shows him walking through a crowded public park shouting his frustration over the lack of affordable housing. We undertook the editing process together over my laptop at an outdoor café.

To recruit audience participants, I reached out to the mayor’s homeless task force, staff working with city councilmembers, a state senator’s office, a federal housing agency, and several nonprofit and government-funded homeless service agencies. Ultimately, 17 policymakers from five institutions and 18 service providers from four organizations participated. My previous research projects and relationships developed from my years as a photojournalist helped in recruiting participants. Most policymaker participants, however, were staff members for recently elected city officials—people I had never met, who were new to their roles. Because of the pandemic, the viewing and discussion sessions transpired through Zoom. After each viewing session and discussion, Henry and I identified emergent themes.

The empathetic connection to another human being’s physical and emotional experiences created through visual storytelling can motivate policymakers and service providers to examine their own behaviors and perceptions.

Visual storytelling evoked powerful emotions in all participants, including Henry, that varied from empathy and compassion to derision and resentment. This range of responses revealed different individual and institutional dispositions toward homelessness, exposing the role of perception as a major disconnect in the homeless services system. For instance, the city’s Homeless Outreach Team (HOT) were extremely uncomfortable with the scene in which Henry walks through the park shouting about housing being a human right. HOT officers—uniformed police officers in marked vans assigned to connect willing individuals with recovery programs or shelters when space is available—said if the purpose of the video is to stimulate compassion, then the person in the video needs to fit a profile that the public is conditioned to care about: that is, a mother with children.

Furthermore, the officers confessed that because Henry had a felony conviction, given their law enforcement lens, they viewed him as an infraction rather than an individual in need. This confession reveals a profound contradiction that results in a broken system. The officers dehumanize the very people they are assigned to serve. One officer joked that homeless stories are good entertainment at parties.

Other service providers and the majority of policymakers were horrified to hear how the HOT officers reacted to Henry’s story. Of the scene in the park, the executive director of a nonprofit agency said, “We all have the privilege of when we’re having a bad day, we can isolate ourselves, we’re not exposed to the elements, to people, and having to act according to social standards. People experiencing homelessness don’t have the luxury.”

Several policymakers, including the mayor’s new homeless task force, said they had already questioned the city’s rationale in assigning police officers to perform outreach with a population that typically avoids contact with law enforcement. Policymakers acknowledged their responsibility as government agents for removing laws and other obstacles that make life difficult for the homeless. Several commented on the importance of engaging with more storytelling from individuals like Henry. One policymaker stated, “There’s consensus that we lack a clear path or enough paths for individuals with lived experience to provide feedback on the city’s policies and programs.” One month after sharing Henry’s story with the mayor’s homeless task force, the mayor announced the addition of clinical psychologists to the outreach teams. He told the press this new approach will be “person-centered, neighborhood-based, trauma-informed, housing-focused.”

Truth and consequences

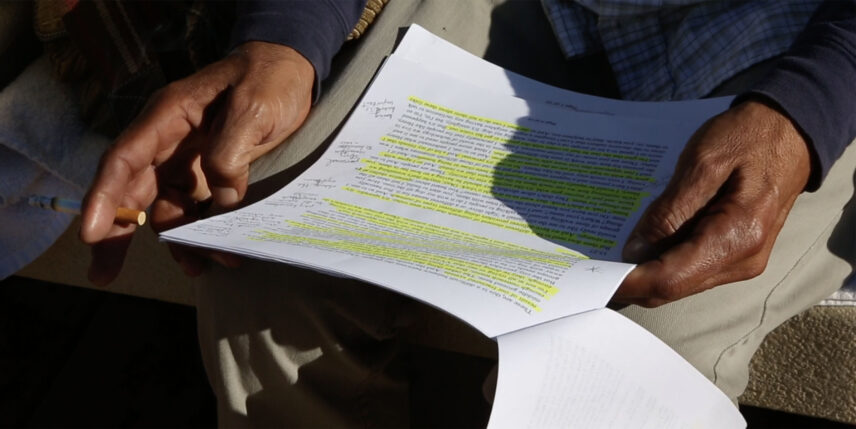

For Henry, sharing his life through the visual critical negotiated narrative resulted in many empowering, uplifting moments. That day on the park bench, Henry reveled in reading aloud the study participants’ praise for his ability to find peace in his watercolors and drawings. They were humbled by his self-awareness—that he needs to make amends if his emotional outbursts offended anyone. Participants agreed with his suggestion that people going into housing after years on the street need a mentor, someone to remind them to wash their clothes and eat fresh food. Henry would be a good candidate for that role, they said. “I may run for mayor,” Henry proclaimed, proud that sharing his story was able to influence policy. “Having a voice gives me that agency,” he said. “I know I’m worth it.”

But this collaborative storytelling also resulted in equally intense moments of rage and despair. At our third meeting to code transcripts, Henry showed me newspaper articles disclosing a bedbug infestation at the single room occupancy (SRO) hotels where homeless individuals were being placed during the pandemic. One of our friends was so badly bitten he went to the hospital. Refusing to return to the SRO, he stayed on the street where he caught pneumonia. Henry’s voice grew louder as he talked about this injustice. He said policymakers and service providers need to spend a week in these SROs in order to experience the realities of homelessness. This set of transcripts contained the aforementioned HOT officers’ comments. Several officers suggested that Henry lied about being diabetic in order to acquire syringes for intravenous drug use. This triggered Henry’s rage. He walked off. When I caught up with him two blocks away, he was tearing up his artwork and tossing the pieces into traffic.

Seeing through the camera’s lens

The empathetic connection to another human being’s physical and emotional experiences created through visual storytelling can motivate policymakers and service providers to examine their own behaviors and perceptions, even to transform existing policies and programs that are ineffective and in some cases harmful. But visual methods can also reinforce individuals’ and institutions’ entrenched narratives about homeless individuals as undeserving.

In a reflection on researching a book on urban policing in France and its reception by the various audiences, Didier Fassin reminds us that social science fieldwork illuminates the unknown and interrogates the obvious, but in order to have impact it must be “simultaneously critical and public.” Pursuing meaningful change challenges us to do the work that motivates people to step out of comfort zones and to have difficult but honest conversations. The visual critical negotiated narrative methodology that centered a homeless individual’s lived experience illuminated what for many people is unknown. This visual critical pedagogy can be used in other areas of social science research involving vulnerable populations. Researchers who are poised to do this work, however, need to be ready to answer the question of whose story is being told, by whom, and to what end.

Author’s note: Coproducer Henry Cabrera requested that his real name be used for this article, as well as any other publication or discussion relating to this project. He is comfortable with the details of his life, including his felony conviction, being disclosed to the public. The video at the heart of this study, Call Me Henry, can be viewed on YouTube.