Article begins

Cancerous Heat in the Body

In the embodied experience of a person with cancer, heat plays a critical role.

Hot flashes and night sweats afflict many patients. Sudden-onset surges of intense warmth followed by profuse sweating can be triggered by chemotherapy, radiotherapy (or radiation), hormone therapy, steroid use, or surgery to the reproductive organs that prompt hormonal changes. Both men and women report hot flashes resulting from disease and treatment; in addition, young female patients may also experience hot flashes due to premature, medically induced menopause to protect ovarian reserves from iatrogenic infertility.

But the effects of heat on cancer patients aren’t confined to discomfort. Neutropenic fever, a condition where body temperature rises dangerously high as patients’ white blood cell counts plummet during treatment intervals, is one of the riskiest complications of cancer treatment. Neutrophils are a type of white blood cell that attack bacteria; because chemo and radiation can destroy neutrophils or bone marrow (which produces neutrophils) as a side effect, patients with cancer are often left with immune systems that lack the ammunition to fight everyday bacteria which would otherwise be harmless. Without enough white blood cells, immunosuppressed patients have deficient capacity to jump-start the inflammatory response necessary to fight infection. Therefore, neutropenic fever in a cancer patient is an emergency and can swiftly escalate to life-threating or life-ending illness.

Certain cancers and their treatments also cause peripheral neuropathy, a nerve-damaging side effect that produces a burning sensation in the limbs, hands, and feet. Not only does peripheral neuropathy create a fiery feeling in the extremities, but it also reduces the ability to sense changes in temperature, making those affected vulnerable to burns and injuries. Another side effect known as hand-foot syndrome (palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia) can cause redness, burning, inflammation, and blistering, resembling a sunburn, on the palms and soles of the feet.

The inability of patients with cancer to thermoregulate (control their body temperatures), the steady risk of becoming febrile, and bodily sensations of burning deeply affect both their comfort and their safety, no matter the climate in which they live. But increasing global temperatures due to the current climate crisis compound the problem, posing further risk of dehydration, heat stroke, and sunburn. Patients who travel to medical appointments and those without access to air-conditioning at home or in hospitals are especially vulnerable.

Cancer and its chemical treatments brings uncomfortable, inevitable, and even dangerous heat.

Cancerous Heat in the World

Not only do smoldering temperatures from the climate crisis worsen conditions for existing cancer patients, but malignant heat also renders well bodies more susceptible to disease. Cancer is already a major public health problem, with over 19 million incident cases and nearly 10 million deaths globally in 2020, and higher rates of cancer (especially lung, skin, and gastrointestinal) are projected to accompany extreme global temperatures.

Outdoor pollution (arising, in part, from burning fossil fuels, coal-fired power plants, oil and gas extraction, and fracking) was classified in 2015 by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a group 1 carcinogen, meaning sufficient evidence exists to conclude that hazardous ambient air particle matter causes cancer in humans. Several other cancers, such as head and neck, oral, liver, bladder, and kidney cancers, have been shown to be associated with polluted air exposure as well. Particle matter resulting from destabilized, overheated natural sources—such as dust, volcanoes, sea spray, and wildfires—also contributes to new cancer diagnoses. An estimated 410 megatons of carbon were released into the atmosphere in 2023 by Canadian wildfires alone; record-breaking wildfires sweeping boreal forests in recent years exposed those residing within 50 km of the fires to carcinogen soot, as well as contributed to greenhouse gas emissions globally.

Prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun’s rays is also a major risk factor for melanoma (skin cancer). The depletion of the ozone layer from greenhouse gas effects intensifies the potency of ambient UV and accelerates the dangers of exposure. Furthermore, regions that have been historically limited in their sun exposure during the cold winter months have now warmed, and those living in these changing climates spend more time outside throughout the year. While many high-income countries have implemented prevention efforts against malignant melanoma, such as educational campaigns like the World Health Organization’s INTERSUN program initiative, individuals living in low- and middle-income nations, especially near the equator or in higher altitudes, remain at increased risk for UV damage. These nations also usually have less medical infrastructure to detect and treat skin cancer.

Gastrointestinal cancers resulting from consuming polluted food and water are also emerging alongside warming climates. As the surface temperature of Earth rises and increased humidity causes excessive rainfall and flooding, the risk of carcinogenic pollutants passing into irrigation and agriculture systems has become a steady threat. After Hurricane Harvey hit the Gulf Coast of Texas in 2017, for example, more than 500 industrial chemical plants, oil refineries, and hazardous waste sites were flooded, and carcinogenic toxins were circulated among residential and commercial irrigation infrastructures throughout the Houston region.

Worsening air quality, broadened UV radiation exposure, and higher rates of environmental toxins are all ways in which the heat of our world is already impacting cancer rates, as well as the comfort and safety of cancer patients.

Metastatic Supply Chains

While scorching global temperatures produce downstream effects that cause higher rates of cancer, healthcare and treatment options for people with cancer are also structurally vulnerable to climate-related disturbances.

Extreme weather events cause power outages that threaten or derail clinic and laboratory operations, medical equipment use and production, and communication systems—not to mention patient transportation—which negatively impact the availability and effectiveness of the infrastructure patients depend on for diagnosis and treatment. Major weather events and the subsequently destabilized or depressed economies in the areas they affect may drive specialized healthcare personnel away, while the residents left behind are already vulnerable and sometimes unable to travel for treatment. Patients with fast-growing cancers are especially disadvantaged, since adherence to a scheduled treatment regimen can mean the difference between life and death, and delayed therapy can devastate prognostic outcomes. A growing body of evidence suggests epidemiological trends toward poorer survival outcomes among populations living in or receiving certain types of therapies (e.g., lung cancer treatment) near regions prone to hurricanes.

At times, it isn’t just nature’s heat that affects treatment “supply chains”; heated geopolitical struggle can have a devastating effect on the ongoing delivery of healthcare, too. One example is the recent Israeli airstrikes in Gaza, which damaged facilities and depleted fuel supply at Gaza’s only cancer hospital, Turkish-Palestinian Friendship Hospital, forcing its closure. Combustible conflict arising from natural resource shortages and land wars is prone to impact healthcare infrastructure as well.

The supply chains that constitute the global medical-industrial complex are highly vulnerable to climate-related disruptions. As such, our healthcare supply chain can be viewed as a human body. Some portions closer to the primary site (where the cancer, or the problem, first occurs) get overwhelmed by the “tumor burden” (the measure of the problem within the system), as when a hurricane causes power outages to a hospital that delivers chemotherapy to patients, while others suffer delayed, downstream effects of “metastasis” (the spread of the problem), as when patients suffer because specialized healthcare personnel no longer live where they are most needed.

Cancer as Pollution

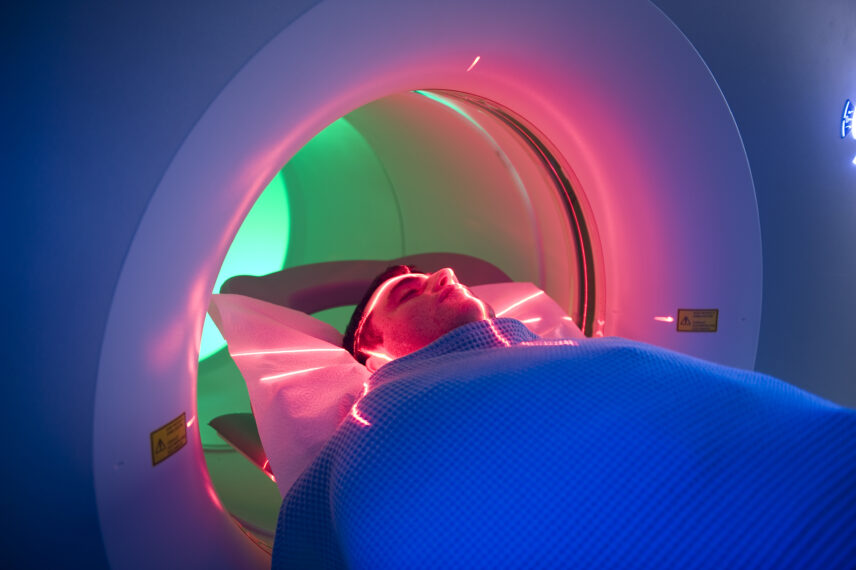

Cancer treatment itself contributes to increasing global temperatures. The US healthcare system is the second-most energy-intensive industry in the United States. The pharmaceutical industry has been found to be significantly more carbon-intensive than the automotive industry, through manufacturing, packaging, transport, and disposal of cytotoxic agents as well as prolific waste from single-use products. Hospitals are consumptive infrastructures, with cancer care relying on some of the most energy-intensive medical procedures, including radiology services, daily fractionated radiotherapy with associated patient travel, radiologic tools and radiotherapy machines, and surgical suites that include greenhouse-gas-producing anesthetic agents. (Not to mention swelling rates of burnout among healthcare personnel, which diminishes the oncology workforce). To date, no known studies have estimated the total carbon footprint of the global cancer-industrial complex. However, given that the rates of cancer are expected to rise along with global temperatures, it’s vital that we move toward more energy-efficient treatment options.

Bodies as Polluted Worlds

Like the human body, Earth overheats in response to both external factors (like chemical pollutants) and in response to internal-systems failures. Both the human body and the planet body are organic entities, pillaged and poisoned and boiling over. While toxification of natural resources caused by humans means there is a tenable link between pollution and disease, there is also a less literal, more transcendent metaphor to be drawn: the cancerous body is an allegory for a planet with advanced-stage hyperthermia.

To tell the story of global warming in the language of cancer is to speak of the body as a mirror for the world, with “embodiment” as a framework for understanding the manifestation of disease. Embodiment is a broad concept, and it carries different meanings in different academic disciplines. In anthropology, embodiment is a way of “describing porous, visceral, felt, enlivened bodily experience, in and with inhabited worlds.” In essence, the “world” and the “body” are intersubjective entities. The world acts upon the body, and vice versa.

This is not a new concept; playwright and activist V (formerly Eve Ensler) tackled the notion of cancer as the bypass between the human body and “the body of the world” in her 2010 memoir In the Body of the World: A Memoir of Cancer and Connection. V authored the subversive feminist play The Vagina Monologues in 1994 and was diagnosed with uterine cancer in 2010. She stated bluntly in In the Body of the World that after having become famous for undercutting stigma around women’s sexuality, “the idea of dying from cancer in my vagina was just too [f––] ironic and weird.” The memoir encapsulates V’s constant meditation on concentric bodies, from her own “cut and lumpy” cancer-ridden body to the planet at large, which she describes as burning down in the face of “a monstrous vision of global disassociation and greed . . . in pursuit of minerals and wealth.” V’s use of metaphor for concentrically situated bodies is so deft that there are passages where scale disappears completely and her discourse on bodies collapses into one—“body and world as mutual metaphor.” Whether she is discussing the planet or her own organs becomes difficult to decipher—and this is her point. As V underwent resection to treat her cancerous fistula, she became obsessed by holes. Her body materialized the singed state of the world; became the blistered, perforated ozone. Life and death, reproduction and waste collided through her broken lower organs, mirroring the state of the polluted world around her. In V’s words, she “somatize[d]” the state of world into her flesh.

To think of the inflamed body as a “somatized” response to a burning planet is to grapple with the boundaries and entanglements. In the article “What Gets Inside,” published in Cultural Anthropology, Elizabeth F. S. Roberts argued that, in a chronically polluted environment, outside and inside are relational fields, and that “maintaining an inside and managing what enters it constitutes a crucial survival response within the continued violent capitalist interpenetration of all the earth’s biota.” Bodily-environmental entanglements in Robert’s case show the way that “insides and outsides” co-occur across different lifeworlds (scales and domains of experience)—whether the cancerous body within or the toxified world around.

To be clear, many Indigenous worldviews uphold the Earth as a spiritually embodied entity. Therefore, the current call to envision our individual bodies as organic refractions of the planet body—with cancer for both at stake—is a distinctly Western revelation. To frame cancer as a direct consequence of the climate crisis is to understand that the cancerous body and the body of the world are both burning from the outside in. To see our flesh in porous relation with the planet enables a conceptual shift toward the intersubjectivity of our anthropogenic actions and reactions, making global warming fundamentally a health emergency. Cancer-affected bodies, already an autoclave of noxious chemicals, are vulnerable subjects in a hyperthermic world around them, around us. The path forward toward survivorship where cooler bodies may prevail demands an integrative view of the climate crisis as a cancer crisis—both literal and metaphorical.