Article begins

Urine matters at the opioid treatment clinic. It matters not just to the patients and the clinicians, but also to a multimillion dollar urinalysis industry that is inexorably entangled with the biomedical complex and the carceral justice system.

If it weren’t for the angled mirrors where the wall meets the ceiling, the toilets would be like any other. Depending on their gender, a male or female clinician will accompany the patient into the toilet, the mirror serving as a kind of periscope to that most everyday of bodily functions: urinating. “The mirrors are there to stop any funny business,” says Sarah. She pauses, cracking a thin smile that sits somewhere between impressed and exhausted. “But that sure don’t stop people trying.”

Sarah is a urinalysis technician working at Rally, an opioid treatment clinic in Eastern Tennessee, in the heart of the Appalachia. And Sarah isn’t kidding when she says that patients try to cheat their urine drug screens. Each device discovered is catalogued in a digital photo album. Sometimes it’s as simple as a condom taped to the inside of the thigh, swollen with clean urine bought on the black market. Other devices are more complicated: travel-sized hand sanitizer bottles placed inside condoms and inserted vaginally; plastic tubes adhered to the underside of penises and connected to urine-filled Ziploc bags tucked away inside pockets. Prosthetic sex organs are also not unheard of. The point is that urine matters. A lot. It matters not just to the patients and the clinicians—whose daily game of cat and mouse can evoke frustration and amusement in equal measure—but also to a multimillion dollar urinalysis industry that is inexorably entangled with the biomedical complex and the carceral justice system.

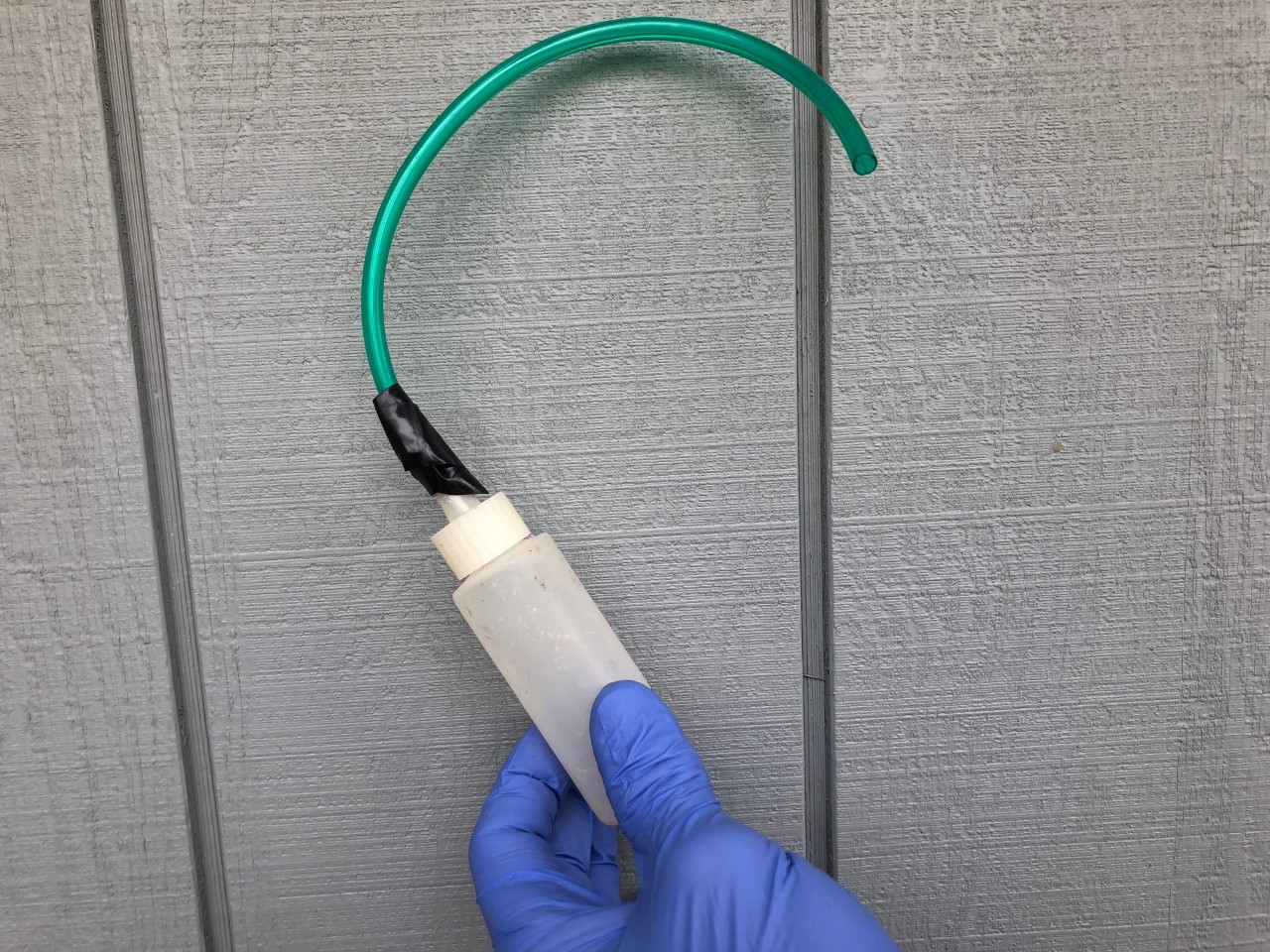

Image description: A hand in a blue medical glove holds a plastic bottle with a green tube taped to it.

Caption: Example of a urine drug screen “cheat” technology, which was uncovered and confiscated by clinical staff, 2020. Clinic director

As a discipline, medical anthropology is no stranger to bodily fluids. Across a broad range of contexts, ethnographers have explored the way in which the exchange and flow of bodily fluids—notably blood and breast milk—work to establish the moral parameters of personhood, interpersonal care, and relatedness. Urine, perhaps because it is typically excreted rather than shared (as in breast milk) or inherited (as in blood), has enjoyed little anthropological airtime. Instead, anthropologists have—with a few notable exceptions— tended to leave the question of excretion to psychoanalysts, who have mostly approached it through Freudian models of psychosexual development. Even these models, though, pay more attention to defecation than to urination. Urine, then, emerges as something of a forgotten fluid. For those who are caught up in the messy world of addiction recovery though, urine is not so easily forgotten. On the contrary, it is rarely off their minds.

The first test the clinic runs is called a “quick cup.” Performed on site, it lets the clinicians know, at a glance, what substances the patient has recently ingested. Ultimately, they’re not looking for clean urine, but rather the “right kind of dirty,” as one of the technicians puts it. Given that all patients at Rally are prescribed suboxone—a synthetic opioid replacement containing a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone—they want to see evidence that the patients are taking their medicine, just their medicine, and nothing else. Urine, in its passage through urinalysis technology, holds a double-edged potentiality, either cementing trust in the therapeutic relationship or else imploding it.

Image description: Photograph of a variety of small, plastic bottles altered with tubing, tape, aluminum foil, and other materials.

Caption: Examples of urine drug screen “cheat” technologies, which were uncovered and confiscated by clinical staff, 2020. Clinic director

For the clinical staff, the two-step test is used in a number of important ways. First, for a patient to have their prescription renewed, they need to successfully pass urine each time they attend the clinic. Otherwise, a doctor won’t see them, and they’ll go home empty handed (a terrifying prospect for anyone with long-term opioid dependence). “No pee, no prescription,” as Sarah puts it. Second, the results of each test will determine the type of prescription patients are offered. When someone fails a test—because of unacceptable levels or the presence of illicit substances—that person runs the risk of being disciplined, by having their dosage cut down and, depending on what prescription cycle they are on, being made to return to the clinic more frequently for refilling. Failing too often can mean expulsion. That said, not all failures are equal. As Jim, a nurse practitioner and director of the clinic says: “Just because you fail a drug screen, doesn’t mean that you and I need to fail.”

To demonstrate what he means by this, Jim gets out a piece of paper and writes the acronym SOAP lengthwise down the page. Subjective. Objective. Assessment. Plan. He explains:

So, subjectively, as you know, is what people say. If someone’s like: “Hey Jim, I’m doing good, I’m staying away from them. Just taking my medicine. House is happy.” So, I’m getting all the subjective—he’s staying clean, no benzos, says he hasn’t used meth in two months. So, I gotta take the subjective stuff he says. And then I gotta take the objective information, which is the stuff you don’t say but what I observe. I haven’t done anything yet, but this guy looks fucked up today—his pupils are big as hell. Oh, his UDS is positive, for cocaine, benzos, meth. Now what he’s saying doesn’t jive with what I’m seeing. So, the perfect visit for me is when what somebody says matches what I see, which then can support a diagnosis. So, if somebody subjectively says, “Look man I’ve been smoking meth for three weeks” and objectively I witness it on the urine drug screen—now we’re jiving, subjective and objective. They have to come to come together to build trust. It creates accountability.

Image description: A hand in a blue medical glove holds a bottle with aluminum foil wrapped around one end.

Caption: Example of a urine drug screen “cheat” technology, which was uncovered and confiscated by clinical staff, 2020. Clinic director

In such an encounter, the patient’s urine—reinscribed through the drug screening process—becomes not just a measure of clinical compliance but, once taken in concert with their own subjective accounts of their drug use, also a mediator in the moral affordances between patient and clinician. Urine, in its passage through urinalysis technology, holds a double-edged potentiality—either cementing trust in the therapeutic relationship or else imploding it. Simultaneously, that same urine sample is also being fed through a complicated matrix of institutional and technological networks that operate both inside and outside of the clinical environment. External lab agencies analyze the urine, often through exclusive contracts with insurance companies. Lab representatives visit clinics and try to push clinicians to sign up to their facilities. Doctors and other care providers seek new ways to use urine testing to bill insurance companies for reimbursement, even when it isn’t in the patient’s interests. Additionally, these testing facilities become de facto arms of the criminal justice system, with failed drug tests being one of the primary causes of violating parole or bail. As Jim puts it, “The lab industry is a whole other cultural phenomenon of greed, people going to jail, kickbacks, corruption, over billing.”

While honesty may be the best policy in terms of building Jim’s “perfect” therapeutic relationship, for those whose continued substance use means potentially going back to prison, prosthetic genitals and a reprimand from one of Rally’s clinicians can seem like a small price to pay. In this respect, the “funny business” that ensues when people try to cheat drug tests cannot help but exceed the therapeutic encounter, as each drop of urine is simultaneously absorbed into the “big business” of what might legitimately be described as the urine-industrial complex. Social scientists who study addiction might well be familiar with the notion of neuroeconomics, a term coined to describe the wide range of economic and political systems that interact as psychoactive chemicals make their way around the social world, being absorbed by human brains, corporate networks, and governmental policymakers alike. Perhaps, then, it is about time for a uroeconomics—one that can account for the way intimate therapeutic relationships, and more specifically the urine samples underpinning them, are always already intermeshed with vast networks of biomedical commerce, carceral governance, and corporate avarice.

Joshua Burraway is a medical anthropologist and research fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia. He researches how historical and structural forces shape different modes of subjectivity, in particular with regards to altered states of consciousness induced by psychoactive chemicals.

Please send your comments and ideas for SMA section news columns to contributing editors Dori Beeler ([email protected]) and Laura Meek ([email protected]).

Cite as: Burraway, Joshua. 2020. “Contemplating the Urine-Industrial Complex.” Anthropology News website, September 16, 2020. DOI: 10.14506/AN.1500