Article begins

Black cowboys prepare to take control as they go about their daily lives, in ways that are skilled and sometimes subtle. Their bodies and the reins are their tools for control. The checklist of assurances the Black cowboy runs through as if it were second nature: securing the bit in the horse’s mouth for comfort and safety, fastening the flank cinch, setting the saddle on the horse’s back, checking the evenness of the stirrups. The rhythm he develops to gather momentum to mount his horse before resuming his checklist by inspecting the evenness of his reins. All is in preparation for leading and guiding a once wild, now gentle, animal to rope, herd, or ride.

The cowboy has traditionally served as a border guard between rural and urban America. To do this, he asserted masculine control over his social and natural environments. Black men in the United States have had limited control over their movement and mobility, but their willingness or pride in preparing to be in control has never fallen short. From 2012 to 2014, I researched Black-owned ranches and rodeos and spent time with Black cowboys to learn how they understand the role of Black men, masculinity, and manhood in country-western culture.

The pride in a Black cowboy’s posture when he is secure in the saddle and in command of his ranch’s operation is undeniable. He enlists the help of his friends to herd cows and calves into the round pen, a ritual process for controlling the animals’ freedom to roam and preparing to castrate the young bulls. The look of control can also take the form of attentiveness and care. I see the subtle shifts in the Black cowboy’s ability to get, be, and maintain control of his environment in a way that is beautifully methodical. When the job calls for reuniting a lamb with its nursing mother and twin by gently walking it on horseback. When the job involves taming a wild horse by making the animal gentle enough to be ridden by a novice or small child.

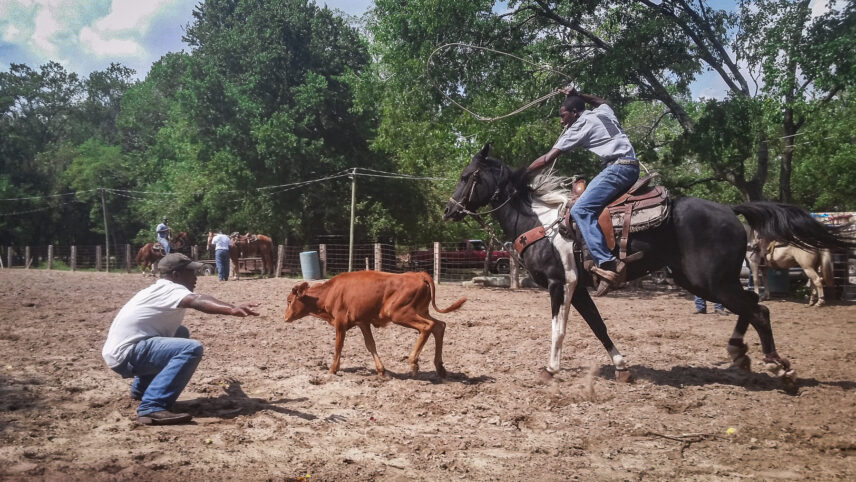

In the rodeo, Black cowboys pay the same attention to their preparation and execution of control as they do when roping calves on a farm or ranch. The goal of this timed rodeo event is to rope and immobilize a steer. A cowboy at a feed store in Houston invited me to watch him and his buddies practice calf roping at a barn across the street. When one cowboy releases a calf into the area where he is caught between two cowboys, it then takes meticulous teamwork, coordination, and cooperation to control which way it runs. One cowboy is on the ground, directly in front of a baby calf weighing at least 215 pounds and running from another cowboy who is chasing it on horseback. They must work together for the mounted cowboy to rope the steer, dismount from the horse, and tie the steer by its hooves. But there is no cowboy on the ground in the rodeo; the magic lies in the partnership between a man and his horse.

On a trial ride, a Black cowboy takes the reins of a covered wagon, pulled by one horse or a team of horses. On either side of the wagon an American flag and a Texas state flag are displayed with pride. This Black cowboy is a vision of dignity for Black American masculinity. He has traditionally commanded the vehicle used by rural Black people moving to urban areas during the Great Migration with his family and culture of Black western folklife in tow. Of course, today, this can be read as a reenactment, but I see elements of this Black western past riding alongside representations of what this new Black cowboy looks like when he is cultivated in the city.

Black aesthetic creativity would have us consider a makeshift two-seater wagon on two wheels with a large white cooler in tow, hitched to a horse controlled by a Black cowboy wearing blue jean shorts, a white tank top, baseball cap, and sunglasses, holding a cigar―not the traditional cowboy uniform worn for the practical purposes of work on the farm or ranch. Yet there is a similar posture of confidence in his control over the wagon, his horse, and his ability to dictate his direction on the road.

To talk with, rope with, and ride with Black cowboys is to experience immense skill and see an expression of Black masculinity at work. The images I took convey this gender performance and a care, playfulness, creativity, and artful control that bind traditional and modern practices.