Article begins

A street in the busy Parisian neighbourhood of La Chapelle echoes with the cracking of wooden sticks and clapping of palms on sabar drums. The vibrating sound escapes from the ground floor of a sports hall where 40 women and one or two men are watching Yama Wade with extreme concentration, executing the dance moves she demonstrates. Tall, slim, and dressed in a light colourful boubou that flows with her steps, Wade walks around the group of students, holding a sabar stick in her hand, scrutinizing each dancer with careful attention to correct a mistake, poor posture, or hesitant arm gesture. Half a dozen musicians sit behind a line of sabar drums in the corner of the room, accompanying the class with their polyrhythmic phrases, dissecting some sabar phrases to ease the students’ understanding—attentive to Wade’s indications, following her instructions.

Wade, who has lived in Paris since 1992, is a highly respected master of the Senegalese music and dance performance, sabar. Dozens of students from all over Europe flock to learn its steps and rhythms by attending dance classes or travelling to Senegal for intensive workshops. On this day of her annual workshop in Paris, Wade teaches a complex dance rhythm called mbabass, that has now faded a bit in Dakar sabar ceremonies, but that sabar enthusiasts in Europe appreciate for its roots in the old sabar traditions. She explains that in recent years, she has reconsidered the way she teaches this step and stopped marking the beginning of the dance move by tapping the right foot twice on the floor: “We [sabar instructors] used to say that to teach white people, we will mark the time with two taps on the floor like in dagañ, because Western people need to have the rhythm on the floor. But mbabass is not like that, that is dagañ.” She then shows the subtle difference between mbabass and dagañ, which are often confused and presented as similar in dance classes, but that should, in her opinion, remain differentiated.

Wade is committed to maintaining what she calls the “original tradition” of sabar as it was back in the days before she left Senegal. She aims at transforming the pedagogy and visions of African dances that have been built to fit the expectations of Western audiences in France, and she defends the need to teach the real rules of this improvised circle dance. Standing against the consumption of sabar and other African dances as a way to let off steam or as a choreographic form, she tries to teach her students the language and vocabulary of the dance that will allow them to improvise, develop their own style, and experience the freedom of creating their own conversation with musicians, as the dance is danced in Dakar sabar ceremonies.

From the 1970s onward, several African dancers settled in Paris and other French or European cities, where they participated in the development of a market for “African dance” classes (then spoken of in the singular). The majority of attendees were white middle-class women, and those classes aimed at transmitting moves, gestures, and musical and cultural knowledge stemming from a wide range of dances from Western and Central Africa. This market is often criticized for the exoticism and stereotyped representations of Africa that it conveys, or for disrespecting the aesthetics and meanings of those dances.

Yet, this dance world also cultivated, from its inception, the development of pedagogy, discourses, and ideologies that criticized exoticization and attempted to valorize the aesthetics, meanings, and specificities of some dances gathered under the label “African dances.” Before Wade, several dancers moved both across this transoceanic cultural matrix that Paul Gilroy seminally conceptualized in 1993 as the Black Atlantic, and a more precise route that several current scholars describe as a Black Mediterranean. Through their moves, they took part in reforming the images of African dances and their transmission abroad through dialogues with global Black and African political struggles, former Senegalese President and poet Léopold Sédar Senghor’s ideology of Négritude, Katherine Dunham’s dance anthropology, or, more recently, through projects of de-Westernization of movements and pedagogies.

Replacing Africa at the heart of the Black Atlantic in the 1970s

The emergence of African dance classes in Paris on the cusp of the 1970s, arose in connection with the post-1968 era of bodily liberation and with a particular moment of reconfiguration in Franco-African relationships, which led to a renewed interest in Africa. This was perceptible politically and economically with the establishment of the political construct that Jean-Pierre Dozon described as “Franco-African state capitalism”―the paradoxical reinforcement of a reciprocal political and economic integration between France and its former colonies, for example, through the attribution of big markets and influential positions to French companies in African independent states or by the exponential growth in African workers called to work in French industries―and by a considerable increase in mobility between France and its former colonies.

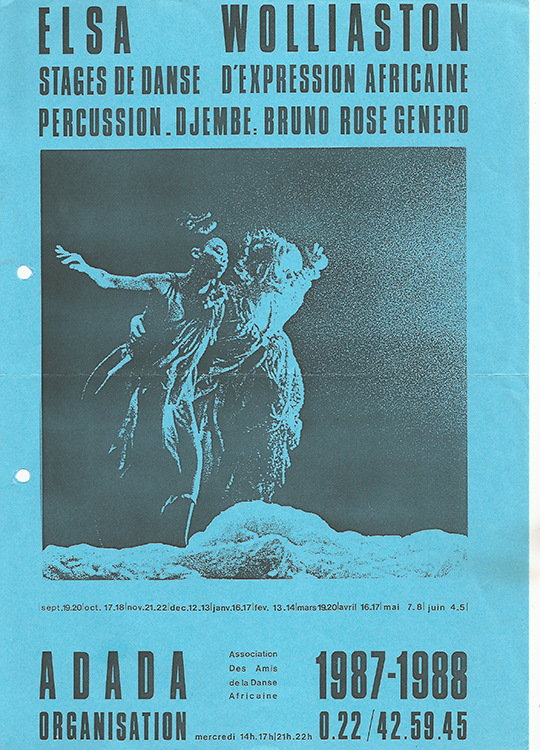

African music, moves, and aesthetics were introduced and appropriated as part of a growing enthusiasm for non-Western bodily experiences. This market first developed in richer areas of cities, in venues such as the Maison des Jeunes Saint-Michel, the Cité Internationale, and above all the American Center on Boulevard Raspail. It is there, apparently, in 1968, that Elsa Wolliaston organized parties where artists from Europe, the Americas, and Africa improvised jam sessions, and where she was invited to give the first African dance classes in Paris.

Born in Jamaica and raised between Kenya and the United States, Wolliaston first trained in piano, ballet, and contemporary dance, notably with Merce Cunningham and the dance anthropologist Katherine Dunham. Influenced by Dunham’s interest in African repertoires, she decided to move to Paris in 1968, when she was 22 years old, to develop her career. During an interview in a Parisian café next to her dance studio, she recounted to me how this move to Paris represented above all a way to get “closer to Africa.” She felt distant from the roots of African dance while in the United States, and she saw Paris as a platform for her personal research project. Speaking about this arrival in France with the historian Nelcya Delanoé as part of their conversation about the American Center, she talks of how she met the “black world” gathered in Paris:

I am a black American and yet I knew nothing of the jazz world or the black world, I discovered them at the [American] Centre―for example Leroy Bibbs, who read his poems to music by Archie Shepp. The Haitian Herns Duplan and the American Suzan Buirge started giving dance lessons, and I started too, with Congolese musicians, with Lucky Zebila, with Guem. I shuttled between Paris and Africa, because I wanted to teach not steps, but peoples, ethnic groups, spaces; I wanted to show that African dance, with its rituals and ceremonies, can meet contemporary dance and vice versa.

This wish to teach African dances in relation to their social and ritual context led Wolliaston to make frequent trips back and forth to Africa, to the villages that she considered to be the source of her knowledge. In parallel with her performances on institutional stages, she quickly made a name for herself through her classes (and she teaches up to this day). She taught a dance called African Expression (in French: Danse d’expression africaine), which aimed at reflecting on the power of innovation and cultural dialogue contained in traditional dance forms. Inspired by the undertakings of African American intellectual and political figures such as Dunham, but also by her family and personal history with Africa, Wolliaston’s classes and performances contributed to a gradual placing of Africa and African dances at the centre of a transatlantic current of reflections and collaborations about the Black world.

At the same period, other artists from the African continent developed classes and performances through which to assert alternative pedagogical outlooks and influences to Wolliaston’s approach―artists like Lucky Zebyla from the Congolese National Ballet or Ahmed Tidjani Cissé who created the Grands ballets d’Afrique Noire in Paris. These dancers were influenced by African national ballets and built new circuits, following the migratory routes between France and its former colonies. Gradually, dancers and choreographers wove routes between specific localities and dance repertoires, reflecting the issues at stake in the construction of national cultures and heritage in independent African nation-states. This would be particularly clear in the pathway of the dancer who created the first sabar classes in Paris and in the route he threaded between Dakar and Paris.

Bringing sabar to Paris in the 1980s

Born the thirteenth in a family of 38 children, Doudou Ndiaye Rose Junior is the son of the famous percussionist Doudou Ndiaye Rose. Early in his childhood, he distinguished himself from his siblings by rejecting the practice of sabar, preferring school to the musical training that his brothers and sisters pursued. Even though he had no real passion for dance, he nevertheless ended up joining the famous school Mudra Afrique in 1980, attracted by the bursaries it offered. As the African branch of choreographer Maurice Béjart’s Centre de Recherche et de Perfectionnement de l’Interprète, Mudra Afrique had been created by Senghor in 1977 in Dakar. As described by Annie Bourdié in her research about this institution, Mudra Afrique responded to the Senghorian project of “modernizing” Black African traditions and promoting Négritude, a notion that the “president-poet” defined as a set of cultural, economic, and political values shared among Black peoples of the African continent and the diaspora, and that was meant to be proudly assumed, updated, and shared with the world. For five years, dancers from all over the continent would be trained at Mudra under the supervision of its famous directress Germaine Acogny, before becoming directors of national ballets in their own countries or instructors of African dances in Europe.

At Mudra, Rose Junior soon discovered his skills in ballet and contemporary dance. After leaving the school, he eventually joined his father’s sabar band as a dancer and musician, which allowed him to travel and perform during big concerts. He decided to stay in Paris after a tour in 1988, and he was soon asked to give African dance classes at the Cité universitaire. Eager to learn more about this repertoire, his students asked him to teach elements of sabar, which was barely spoken of in Paris dance classes at the time. Talking with me about this first experience of teaching sabar, he described his total disappointment:

It was so mediocre… To the point that I almost yelled at my students. […] Because I thought it was innate, that you are born with it. I put something together [choreography], and I couldn’t remember what I had put together. When I changed the steps, people said “no!”. It was a class that went wrong. I went home and called my father. I just understood that being a good dancer is not only about dancing in sabar dance circles, when the whole Medina [Dakar district] and everyone else are cheering for you, that girls think you are handsome. In fact, I’ve just understood that it’s as technical as ballet, or as complex.

From then on, Rose Junior decided to learn more about the different dances of the sabar repertoire, their origins, and ways of performing the movements, under the guidance of an elderly aunt. While gradually focusing on sabar, his teachings remained framed by the pedagogy acquired at Mudra Afrique. In later explanations he recounts advocating the purification and embellishment of these dances, which he intended to present in their most refined version. Denouncing the overpopularization of other African dances and music, his pedagogy aimed both to preserve the traditional “purity” of sabar and to enhance it through Western creative techniques. His emphasis on choreography and the decomposition of movements remained in line with Acogny’s and Senghor’s ideologies of modernizing traditional arts through the use of classical and modern Western choreographic techniques.

Like Rose Junior, some of the artists who arrived in Europe in the 1980s were still strongly influenced by the knowledge and ideologies conveyed by post-independence African choreographic formations, such as Mudra Afrique and its adaptations of the theories of Négritude. Their distinction between a cultivated and a degrading way of approaching African dances, and their wish to differentiate themselves from exotic visions denying the technicality of these dances, would be renewed by generations of sabar instructors who settled in Paris and other European cities in the following decades. Indeed, the 2000s saw the diversification of the field of African dances and the rise of a sector devoted to sabar. It was at this time that Wade became famous and developed her project of de-Westernizing dance pedagogy by criticizing the choreographic approach of these dances and teaching her students the unrestrained way to dance sabar and interact with musicians.

The transmission of African dance repertoires is a complex and much debated product of histories of mobility, relationships, and cross-fertilizations between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. These classes for African dances, although partly reproducing an exoticizing fascination for Black bodies, cultures, and traditions, also and paradoxically fostered many attempts at creating visibility for Black and African artists in French and other European cities. Counter-exotic practices emerged from conversations between travelling artists, Black political leaders and intellectuals, and ordinary dancers and enthusiasts who moved throughout the Atlantic and, increasingly, Mediterranean worlds. These transoceanic movements still infuse neighbourhoods like La Chapelle with sabar moves, and link Paris and Dakar within a common translocal sonic and kinaesthetic landscape.