Article begins

Rites of passage involve challenges. Since American culture does not provide a traditional challenge for those entering retirement, I decided to craft my own. As a boy I heard stories about my maternal and paternal great grandfathers crossing the continent to reach California in the late 1840s and early 1850s. Finding walking relaxing, and having attended a one room country school (three if you count the two outhouses), I learned to always walk facing and be aware of traffic, so I decided my challenge would be to walk across the nation. Once a bicyclist who had been drinking brushed me with her handlebars, a no harm-no-foul event, but I had no close calls with motor vehicles. Likely it was easier to walk west to east than east to west as my ancestors did. Prevailing winds across the nation are from the west so generally wind was at my back rather than in my face, as it would have been in theirs.

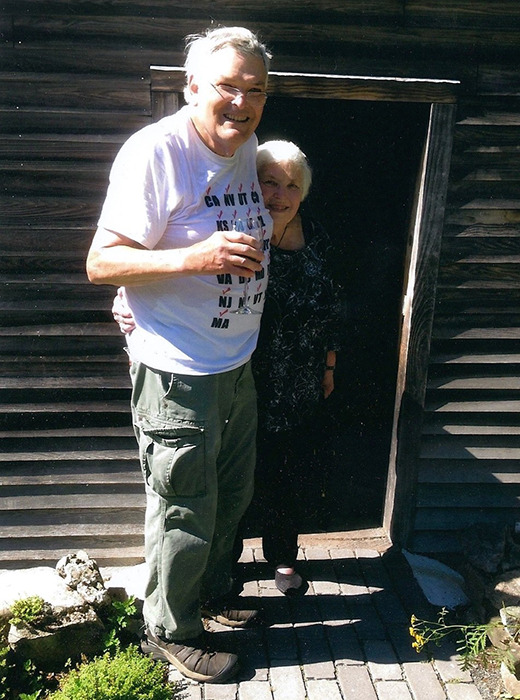

My wife, Carole, and I decided on an indirect route, hitting places that had meaning for us. Some were associated with memories and family legends. Some reflected the way the nation has changed. We decided to end the walk at the Fairbanks Family House in Dedham, Massachusetts. Built in 1636, anyone with a Fairbanks in their ancestry can trace their descent to it. We concluded by walking through the front door of the house that one of my ancestors, centuries ago, walked out of.

As a cultural anthropologist, I decided to study the nation impressionistically as I went. When asked what cause I was walking for, I answered, “None. Many are worthy, but Americans are burdened with causes, making it difficult to work together for the common good.” Some were startled, but no one disagreed. Most were probably being polite, intending to donate if I stated a cause they didn’t disapprove of. Occasionally people gave me money ($48 cash), plus gifts in kind, totaling a great deal more than $48, frequently bottles of water but other things, including a Christmas tree ornament and meals, all greatly appreciated. Many were touching and memorable experiences.

Preparations drove me crazy. Finally, Carole said, “Start walking, we’ll figure it out as we go.” So, on July 3, 2009, I walked out of our front door and 12 miles later reached our son’s house in San Luis Obispo. It worked!

People frequently asked how many pairs of shoes I wore out. Eight. What kind of shoes did I wear? Various types. My advice is, find shoes that are comfortable and wear DryMax socks, which prevent blisters. I didn’t discover them until 2012 when I returned to Los Osos for the holiday season. One evening, as I was getting out of our spa, part of the wood deck collapsed. I fell a couple of feet and got a deep gash under the toes of my right foot which required surgery. When he cleared me to resume my walk, I commented to my podiatrist that I would have to go through the blister stage again to rebuild callus. He advised me to wear DryMax socks to avoid blisters altogether. That year I began walking from Cane Ridge, Kentucky, with the Appalachian Mountains dead ahead and got nary a blister crossing them. (Full disclosure: I don’t own stock in DryMax, nor am I employed by them as a public relations agent.)

Often I was questioned about the roads and trails I walked. Pedestrians can’t use freeways so, with one exception, I didn’t. (People I talked with agree it is safer, at least in rural areas, to walk on freeways since shoulders are wider.) Sometimes I walked on county roads, but usually US and state highways. Carole didn’t follow me, but dropped me off in the morning where I stopped the day before and picked me up in the late afternoon. She knew my route, and when she was looking for me, she could follow the highway signs since highways change from street to street as they weave through towns. Trails I avoided unless I knew where they led and how I could get back to the road in time to get picked up. During the day Carole returned to the motel where we were staying and quilted. Although frequently she quilted at a quilt store, shopped, or visited local sights. During my walk, she completed 38 quilts.

It was difficult to calculate how far I walked each day until, in 2012, our son Bill advised me to install Map My Walk on my cell phone which allowed me to determine distances with greater accuracy. Bill calculated I walked 486 days, covered 5,605.75 miles and averaged 11.53 miles on days I walked. My longest day was 22 miles.

Biographies and autobiographies by people who had done this in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—men, women, old, and young—and I agree: there is a lot of time to think and you are in better health when you finish than when you start. Even when I took breaks and returned to Los Osos for the holidays, I felt invulnerable to germs. In retrospect I am not sure why I bother getting annual flu shots. In the evening, when oncoming traffic was heavy and the shoulder narrow, thinking was focused on walking safely; otherwise, there was a lot of time to contemplate what Carole and I were seeing and experiencing and how the nation and its various regions have changed. Clifford Geertz referred to this approach as using “convergent data,” defined as “descriptions, measures, observations, what you will, which are at once rather miscellaneous, both as to type and degree of precision and generality, unstandardized facts, opportunistically collected and variously portrayed, which yet turn out to shed light on one another.”

In the evening I wrote up the experiences of the day, together with my thoughts about them, and emailed Daily Updates to people requesting them. Falling behind in this I occasionally took days off to get caught up, though rarely did I ever get completely caught up. People receiving Daily Updates frequently commented on them and posed new questions. Many indicated what they liked: accounts of casual encounters I had with people, meetings I attended, descriptions of areas I walked through, and my anthropological perspectives. If everyone liked the same thing, writing up the experience would be much easier. Utilizing convergent data added to the difficulty as experiences at different times and places connect, something anthropologists know. Organizing and weaving these diverse experiences and thoughts together has proven a great deal more difficult than the walk. While editing my material, I read Jane Smiley’s article about the artist Grant Wood which spoke of “the mystery of complexity.” Wood found that every square mile of southeast Iowa on which his art focused invited contemplation. As a pedestrian, I would adjust this to lineal miles, although looking to either side of the highway perhaps it approached lineal square miles. Smiley felt no artist could unravel all the complexities. I would add nor can any anthropologist, nor for that matter anyone. However, if you want a deeper understanding of complex mysteries, you must follow Senator Heidi Heitkamp’s advice and “check your ideology at the door.”

Reflecting on my experience, I read Simon Winchester’s article “The long, sweet road to Santiago de Compostela,” describing a traditional pilgrimage from Paris, France to Santiago de Compostela, Spain. My walk, like the Spanish pilgrims’ journey, had an unintended transcendental aspect. Pilgrims found “the deepest pleasure in one aspect that is measured on a more human scale: it allows each of them to experience the simple kindness of their fellows—a kindness and a caring that, one might think, has almost vanished from the modern world.” Dorothy King, a British pilgrim, expressed it this way: “[it] put me in touch with ordinary Spanish people. And…even put me in touch with myself…testing myself, thinking about things, getting to know my limits.” When asked if it had “fulfilled its promise,” she replied, “no doubt at all.”

Fear in America is palpable. I was warned to avoid cities and neighborhoods considered dangerous, but when walking through them, I was frequently told, “The nation is governed by fear, you are ignoring it and just walking through it, you must be blessed!” They then usually blessed and wished me well. My walk was secular, but as I interacted with fellow Americans, the pilgrims’ interactions with Spaniards resonated with me.

Palpable too was the decline and hopelessness of the middle and working classes. Frequently working two or more jobs, they are ignored by both major political parties and academics. Early in 2016, speaking to a Rotary Club I mentioned, based on what I had seen, Donald Trump had a real shot to win the Republican nomination. At the time, media political commentators saw him as a sideshow; the Rotarians were incredulous; however, after hearing what I said many did a volte-face.

Many felt my walk was crazy, others awesome. Kristen Conner interviewed Carole and me for television station WVVA for the 6 and 11 o’clock news, and listeners were invited to call in to vote: was I awesome or crazy? It was nip-and-tuck, with crazy running a bit ahead last I heard. An alert 99-year-old woman Carole and I met in Maryland said most people “exist,” but you two “really live.”

People I talked with insisted I write up my experiences, which I am attempting, as a series of themed pieces, organized chronologically and hence also more or less geographically. Using convergent data, a piece centered in one state and year might incorporate information from other times and places. Being themed, readers can pick and choose, skipping topics that don’t interest them. They can be read from several perspectives—as an adventure story, as history, regional variety, cultural change, or as national character.

British historian Edward Carr believed people should study historians as carefully as they study the histories they write, a principle with broader applications. Politicians, clergy, teachers, news commentators, and social media should all be scrutinized in this way. A great deal about my background is revealed in the themed pieces, so readers can judge where I am coming from.

As anthropologist, what do you think? “Existing” or “living?” “Awesome” or “crazy?”