Article begins

Frances Kvietok Dueñas is the recipient of the 2019 Council on Anthropology and Education Frederick Erickson Outstanding Dissertation Award. Here, she recounts findings from the ethnographic study that is the basis of her award-winning dissertation, “Youth bilingualism, identity and Quechua language planning and policy in the urban Peruvian Andes.”

Diana walked around her rowdy Quechua classroom, trying to encourage her high school students to perform a Quechua song, a graded assignment. More than half the class had yet to participate. Today was not an uncommon day in class. Somewhat frustrated at the lack of participation, Diana told the group “Ustedes llegando a secundaria les ha dado amnesia … ya no quieren hablar” (“now that you’ve arrived to high school you’ve gotten amnesia … you don’t want to speak [Quechua]”).

During 2016 and 2017, I was in Urubamba, a provincial capital of the region of Cusco, Peru, conducting my dissertation research on the prospects of Indigenous language education policy, with a focus on Quechua, the most widely spoken Indigenous language in the Andes. Even though Quechua language education in Peru has long been relegated to rural areas, regional policy had opened an opportunity for Quechua to be taught in urban high schools as a subject area. Quechua education was now available to a wider group of students—high school youth in urban areas, with a range of bilingual abilities and language socialization experiences.

Image description: A photograph of a large urban settlement in a valley surrounded by mountains and a blue sky with some clouds. The urban settlement is composed of several rows of buildings and roads, with green fields and trees on its outskirt, and flanked by a river.

Caption: Photograph of the town of Urubamba located in the Peruvian Andes mountains taken from a nearby mountainside. Frances Kvietok Dueñas

Diana’s high school, Sembrar School, was one of the two schools where I conducted observations and participated as a teaching aide and volunteer. Early on, I learned about the challenging conditions under which the 45-minutes a week Quechua course took place, including teachers without adequate preparation and a lack of curriculum and teaching materials. These conditions often resulted in Quechua classes characterized by grammar-centered pedagogies, a strong focus on teaching Quechua writing, and teacher control of classroom participation. While classes were lively with student chatter, most often student exchanges were not course-related and frequently not in Quechua, as class activities had a very limited focus on developing oral Quechua abilities. As I spent more time in school hallways, cafeteria, and classrooms, I increasingly heard comments like Diana’s opening statement. Observations on students’ participation and lack of participation in Quechua class became evaluations of language proficiency and personal traits. Among these evaluations, teachers identified youth they believed could speak Quechua but didn’t want to as language deniers. Being a Quechua denier was linked to individuals’ lack of cultural identity, shame, and uninterest in the Quechua language and Quechua course.

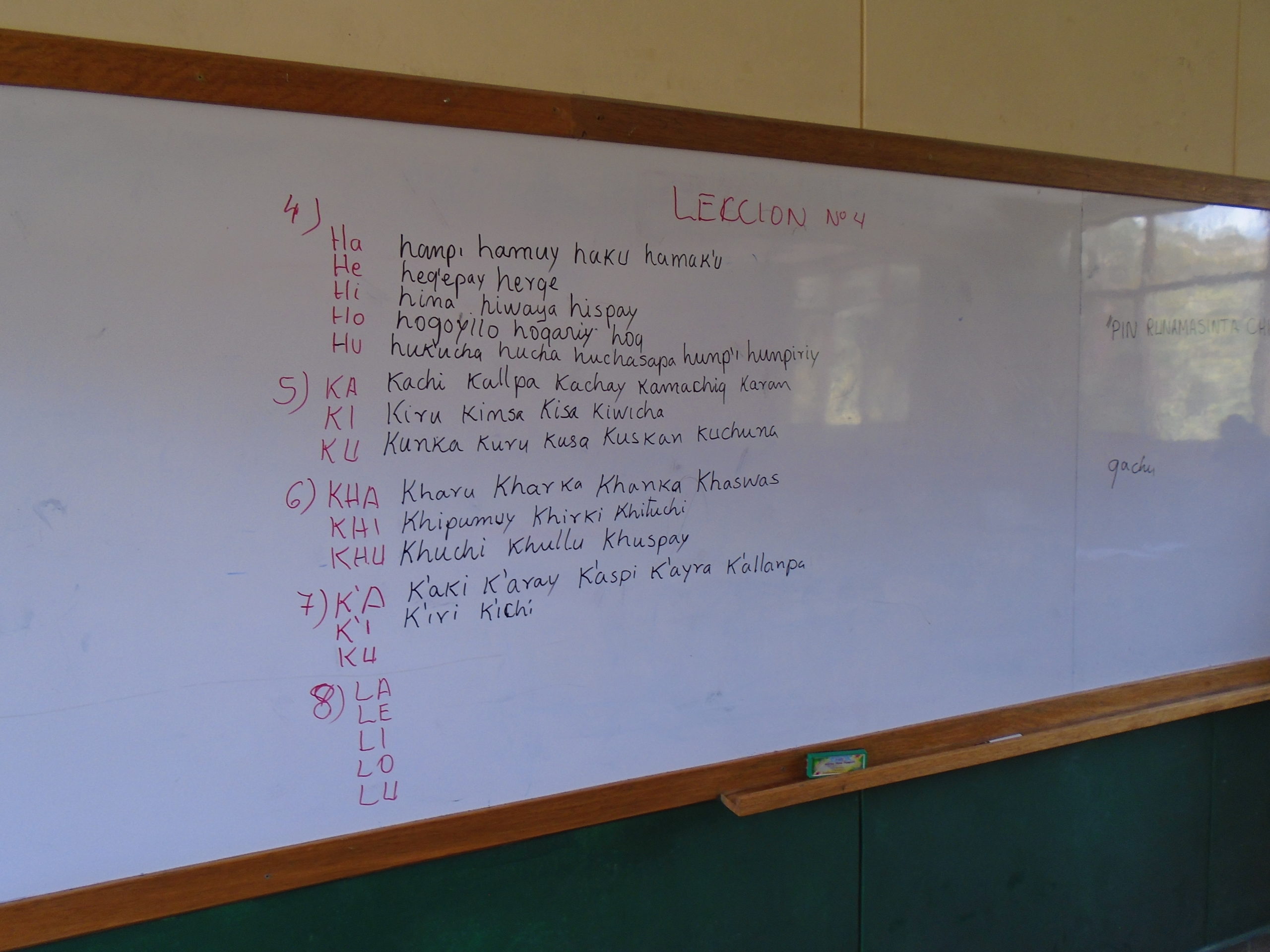

Image description: A photograph of a classroom white board in a Quechua classroom with text written in Quechua syllables, consisting of a title in red coloring and four blocks of text in red and black coloring, listed one after the other.

Caption: Photograph of a whiteboard in a typical Quechua class with sample words written with Quechua syllables. Frances Kvietok Dueñas

If schools were sites where Quechua learning was to be promoted, why were schools also sites where discourses about youth indifference and disloyalty to Quechua abounded? And with what consequences? Learning about 12-year-old T’ika’s Quechua classroom experience helped me explore these questions. T’ika stood out because of her energetic personality and status as a peer leader. During visits to her home, she shared how she had learned Quechua from her great-grandparents as a young child, using it to playfully tease her elementary school friends, but at the moment felt she had lost much of it. At the start of the school year, I noticed how T’ika didn’t stand out in Quechua class, but throughout the course of the year, she became identified by Diana as a Quechua denier: someone who knew the language but did not care to speak it nor learn it. How exactly had that happened?

The student body of Sembrar School was largely composed of youth from the countryside. The longstanding student stereotype was that of rural youth who could understand and speak Quechua, supposedly transmitted across generations. This understanding underlined Diana’s opening statement as well as other teacher commentaries. For example, at a school fair, T’ika and her classmates were evaluated by a group of jurors, who asked them to describe in Quechua what they had learned in class. As the students remained hesitant to participate, one jury member told them “imayna wasipi rimanchis aqnatayá rimankichis” (“tell us just like you speak at home”). Yet, in Tika’s case, her everyday home interactions didn’t involve her using Quechua orally with her bilingual parents and grandparents, not even with her Quechua-dominant great-grandmother, though she could understand very well what her relatives expressed in this language.

Image description: A photograph of a school classroom with green and light-yellow walls, windows on top of one of the walls, and a projector hanging from the center of the ceiling. Student desks are arranged in three columns, with two desks per column. Students write on their notebooks.

Caption: Photograph of a high school classroom in Urubamba showing students completing their classwork. Frances Kvietok Dueñas

Teacher knowledge of students’ lives outside of school is often seen as helpful information to organize meaningful learning opportunities. In the case of T’ika, however, Diana’s knowledge of T’ika’s past language abilities played to her disadvantage. For instance, after T’ika explained she had difficulties participating in an oral grammar-based activity, Diana seemed a bit unconvinced by this explanation, sharing how she recalled hearing T’ika speak Quechua as a child: “sí te sale mami, si tú hablas bonito… te he escuchado hablar bonito” (“yes you can honey, you speak nicely… I have heard you speak nicely”). Diana also told T’ika she did not care about the course, even though she was willing to give her a good grade. In this case, T’ika’s childhood repertoire remained as an indicator, and even an expectation, of what she ought to be able to do several years later. In this way, teacher evaluations disregarded the fluidity of youth’s trajectories. While in the case of some youth, their language trajectories moved toward Quechua across time, in many other cases youth trajectories moved away from Quechua in a context of ongoing language shift.

Even though T’ika was hesitant to participate in some whole-class, public, and graded classroom events, she did participate in several classroom activities. For example, she helped peers achieve tasks and translated and interpreted peer responses for her teacher. Yet, as her identity as a Quechua denier solidified, these practices were less and less recognized by her teacher. In addition, language practices which did not fit the ideal of “school Quechua”—grammar-specific language and school vocabulary—went unnoticed. In other cases, T’ika’s bilingual participation, mixing Quechua and Spanish, was looked down upon, even though it was a fairly common practice among teachers and students.

Being identified as an unruly student in an already rowdy class did not play out in T’ika’s favor either. Arriving late to class repeatedly, speaking back to the teacher, and being the only girl to sit with a group of boys in the back of class, positioned her far away from being a “good student.” Teacher assessment of her classroom behavior brought along negative evaluations of T’ika’s character and conduct, which seem to color teacher perceptions of her language learning abilities. Urban Quechua language education faces many challenges, one of which is pushing away the population it intends to serve.

The experiences of T’ika, and of her teacher, were not unique; I met many Quechua teachers and youth who experienced similar mis-encounters and frustrations in interactions where teachers over-assessed students’ Quechua abilities and undermined youth’s language learning interests and needs. On the one hand, youth described feeling “very bad,” “unmotivated” and “powerless” in many of these encounters. While they sometimes spoke back or tried to clarify their interest in language learning and disillusionment with the course, many times they kept quiet, signaling resignation, distancing from the situation, and respect for teacher authority.

On the other hand, making sense of students’ Quechua language abilities within exacting teaching conditions such as the ones encountered at Sembrar School caused strains on educators like Diana. Addressing the gap between teachers’ assumptions and youth’s communicative practices was an ongoing challenge for Quechua educators. Without teacher education, which provided opportunities for teachers to learn about changing sociolinguistic ecologies and teaching strategies that could best respond to learners’ profiles and needs, teachers found it hard to question and transform some of the teaching practices and ideologies that lay the ground for identifying youth as Quechua deniers.

Urban Quechua language education faces many challenges, one of which is pushing away the population it intends to serve. We know that schools often ignore or misrecognize minority students’ language practices. In the case of urban Quechua language education institutions, we see how educators’ recognition of students’ language abilities is not necessarily empowering, especially if this recognition is accompanied by discouraging evaluations of learners’ characters and ignores their language learning trajectories, needs, and interests as well as contemporary sociolinguistic ecologies. While schools can create language deniers, my research also documents how youth resisted this identification, how youth and teachers created new spaces where youth’s Quechua abilities and interests were uncloaked, and the many hopes and dilemmas of those who participate in the day-to-day project of Quechua language education.

Frances Kvietok Dueñas is a lecturer at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and obtained her PhD in educational linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania. She teaches, researches, and consults on bilingual education and language policy using ethnographic and collaborative methodologies.

Cathy Amanti and Patricia D. López are contributing editors for the Council on Anthropology and Education’s section column. If you would like to contribute, contact us at [email protected] and/or [email protected].

Cite as: Kvietok Dueñas, Frances. 2020. “Creating Language Deniers in Quechua Education.” Anthropology News website, June 17, 2020. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1416