Article begins

My cousin Klára had heard it on the radio, read all about it in emails circulating among her friends. She had seen the evidence in newspapers and magazines and talked it over with patrons in her shop for years. They all knew there were Soros agents in Hungary. It was by no means a secret. Even Figyelő, one of the major Hungarian periodicals, had released a list with the names of actual Soros “mercenaries” (as the prime minister called them). These hired agents had infiltrated Hungary to help assist the “Soros Plan,” a plot by billionaire George Soros to alter the ethnic composition of all the countries in Europe by paying immigrants to move there from the Middle East and Africa. He even encouraged gender confusion, wanting the trans community to grow among “ethnic Europeans” so that they—Klára and her friends, the real, Christian Europeans—would eventually die out.

Klára had heard that Soros agents work undercover, as politicians, businessmen, and especially academics. She had read that the agents write reports every day and send them to Soros every night. She knew that Soros financed them with fellowships from his Open Society Foundation and from the Central European University (CEU). She wanted nothing more than to stop this madness, to preserve her homeland, and to help Prime Minister Orbán tell people what was really going on. Klára knew she would have to start by confronting me.

“I know what you do. What your real job is.”

I was in the kitchen, making a coffee to take back to my desk while Klára cared for my two-year-old son. Her tone caught me off guard. “Come again?”

“I know you’re egy Soros-bérenc [a Soros agent]. You send him the reports you write every night. You meet the others in CEU.”

Klára had accused me before of befriending Soros agents, but this was the first time she had accused me of being one myself. I let out a sigh, saddened at the accusation. “I’m not a Soros agent. I’m an anthropologist. Every night I write notes about what I saw and did that day so that I don’t forget. And I only go to CEU for language lessons.”

“Please don’t lie. I know you work for him. I know that your money comes from Soros.”

“It doesn’t. It’s from the United States government!” I exclaimed, feeling immediately as though I had somehow dug myself deeper into this misapprehension.

This conversation continued for five or so minutes. I failed to convince Klára of my innocence. Eventually, she shook her head and walked away, distraught and disappointed. “I know what you’re doing. I know.”

Klára, a member of my longtime and trusted kin network, told me she knew I was a spy for Soros. She knew that I was somehow trying to destroy the Hungarian nation; the party in power, Fidesz; and Viktor Orbán. To be clear, I was not, nor am I now, a Soros agent. I could not be one if I wanted to. Soros agents, Soros mercenaries, and his vast network of spies do not exist. Szilárd Németh, a Fidesz party member, was the first to animate Klára’s personal truth with remarks at a press conference held to clarify comments made by the prime minister a few days earlier. Her truth was then strengthened and confirmed in her numerous networks, via conversations with select friends and family.

Political reality in Orbán’s Hungary

This myth and collection of lies built around George Soros is one example of Prime Minister Orbán’s daily practice of producing political “truths” for distribution to citizens in contemporary Hungary. As Fidesz controls the majority of Hungarian-language news outlets and public advertising spots, Orbán can counter any truth he does not approve of with his own, via public “informational campaigns.” These unproven claims and conspiracy theories turned prime-time news have become mainstream in Hungary. The Soros-terv (Soros Plan), a supposed plot that threatens the Hungarian state—illustrated above in Klára’s narrative—has spun many similar myths since it entered popular circulation in 2017.

While Orbán spends public dollars to promote and write policy for personal gain, threatening those who report facts to the public, he actively obscures political and social reality. Ironically, he has long cried “fake news” to his supporters when faced with accusations of authoritarian-style leadership and cronyism. In 2020, parliament granted Orbán emergency powers without temporal limit to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Although those powers have since been rescinded, among the laws Fidesz hastily crafted to “protect Hungarians” from contracting the virus was one that promised prison time for the distribution of “any untrue fact or any misrepresented true fact.” In writing about the overuse of executive power, scholars of law and politics David E. Pozen and Kim Lane Scheppele claim Orbán’s law, which prompted immediate protests from institutions promoting free democracy, was the most obvious instance of executive overreach in the time of COVID-19. In the meantime, parliament ended legal recognition of the trans community and classified documents related to the national railway, all while Hungarian citizens began dying of COVID in hospitals that were in desperate need of more government support.

“He’s someone who tells us what to do, but we need someone to tell us the truth. Instead, we get bread and circus.”

The campaign against Soros ebbs and flows but remains ever present. In July 2021, the government sent out a new “national consultation” on “life after the pandemic,” as part of a series of suggestively worded government surveys that Fidesz claims legitimize its democratic processes. Question 10 reads:

George Soros will attack Hungary again after the pandemic because Hungarians are against illegal migration. Some say that we should resist pressure from Soros organizations, others say Hungary should concede in the migration debate.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

A: Hungary must resist pressure that is applied by Soros organizations.

B: We should concede in the migrant debate.

This question relies on “Soros” being read as a threat to the Hungarian nation, to Hungarian social norms and lifeways. Its framing is blatantly misleading, as Soros has never before attacked Hungary and therefore cannot do it again. Writing about charismatic leaders who deploy the law to consolidate power and to remain in office indefinitely, Kim Lane Scheppele calls Orbán’s manipulation of texts and political reality a form of “autocratic legalism.” For Scheppele, Orbán as autocrat changes Hungarian law to fit his political and personal agendas, to reflect and shape the reality he would like to see. The prime minister has amended electoral law in his favor, prompting political scientists Péter Krekó and Zsolt Enyedi to call elections “free but not fair.” Hungary’s electoral rules are so obscured in bureaucratic processes that political scientists Frances McCall Rosenbluth and Ian Shapiro call them “incomprehensible.” Writing about how Orbán worked to place the party and the state under his own control, Bálint Magyar characterizes Hungary as a “post-communist mafia state” in which Orbán is the godfather and the legal system is his weapon of choice.

Communicative strategies and personal truths

Many people in Hungary are highly aware of Orbán’s manipulation of truth and reality via his legal toolbox. While conducting dissertation fieldwork in Budapest on contemporary political discourse, I talked with many Hungarians about domestic politics and government propaganda. László, a middle-aged entrepreneur who often complained about Orbán and voted for “anyone who was not Fidesz,” saw through Orbán’s charade, but admired his abilities as a politician: “He’s a clever, strange guy—a good speaker with charisma. I don’t hate him, but I don’t agree with him. He built a new dictatorship, better than the old Western countries… He’s someone who tells us what to do, but we need someone to tell us the truth. Instead, we get bread and circus.”

In using Juvenal’s phrase, wherein the state provides basic needs and placates or distracts its populace from its more nefarious activities with entertainment, László expressed his understanding of being purposely misled and his perceived powerlessness to change it. He believes that this constant manipulation of law and truth has delayed Hungary on the road to democracy, if there is such a road. “Fidesz learned how to use democratic rules to control us, but Hungary is not necessarily a democratic country. We have to grow into it.”

Much of Orbán’s communicative strategy relies on the creation of new texts as anthropologists Michael Silverstein and Greg Urban conceive them—words and phrases that are the building blocks of human cultural worlds. For example, a Fidesz party member deploys an existing, familiar text, such as “Christian democracy,” and assigns it new meaning. Today, Orbán uses “Christian democracy” to define his party’s mode of governing, claiming that it is “Christian” because ethnic Hungarians are culturally Christian, not Muslim. Yet this definition clashes with the practices and policies of established Christian democrats all over Europe.

Because many Hungarians are keenly aware of this politically motivated manipulation of meaning by their government, they consciously participate in the processes of polysemy, assigning multiple, sometimes contradictory meanings to words and phrases. This is true for Orbán supporters, his opposition, and everyone in between—especially in the case of the Soros mythology. The great majority of people I interviewed while conducting fieldwork were conscious of Soros as a possible political actor and of the way Fidesz wanted people to see him, even if they did not find Soros himself a threat. Michael Silverstein thought of a text’s implicit, multiple layers of meaning as “indexical orders.” Arguably, it is here, in these layers of meaning with varying levels of salience, where personal truths are conflated or confused, where they fester and mature, or where, as linguistic anthropologists Susan Gal and Judith T. Irvine have noted in their work on ideologies of linguistic and social difference, their production is suppressed, erased from conscious thought.

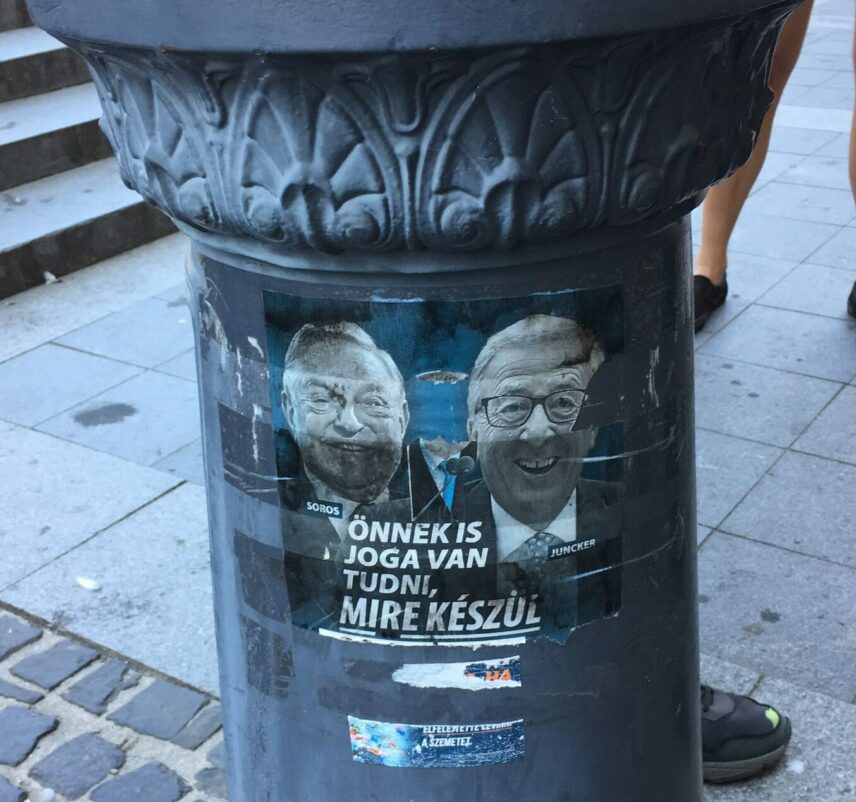

The longevity of the government’s multimodal communicative practices (informational campaigns; posters on the streets; and a constant stream of propaganda on TV, on radio, and in print periodicals) has increased the saliency of select layers of meaning in select texts. Today, Hungarians expect to see Soros on billboards portrayed as a bogeyman and to hear newscasters talk about his evil plots on the radio and on TV. They can create and circulate new memes on social media from their preloaded bag of Soros jokes as soon as the government starts a new campaign.

In this land of multiplicity, individuals negotiate different personal truths in which the saliency of one indexical order over another is not something that can be predicted along party lines. I talked to people who reproduced party slogans verbatim, but who voted for the opposition. I spoke with others who voted for Orbán but did not believe anything they heard on “government-controlled” TV. Orbán’s constant production of truths, which reminds many Hungarians of the socialist era party rhetoric that was intended to distract citizens from political issues of import (Nullius in verba!), has deeply affected trust in institutions and conceptions of reality. Many find themselves disillusioned, blinded to political facts. As a result, some have turned inward and focus only on the needs of their immediate families, just as they did before 1989. Sitting on Margaret Island on a picture-perfect sunny day in Budapest, I was shocked to learn that the intensely liberal man I was interviewing regularly voted for Orbán. His reasoning? “All politicians are liars, you just have to choose the one who steals the least, or the one who will steal for you.”

A safe place for political talk

In Hungary (and elsewhere), where political corruption is quotidian and public trust is below sea level, linguistic anthropologists have a responsibility to explore how truth develops in everyday discourse and, critically, to examine where and how it is maintained. We must also acknowledge the complex system of meaning making and strive to foster multidisciplinary relationships that can help us piece together a multimodal analysis of (political) communication. Establishing multidisciplinary presence can further our understanding of how individuals negotiate epistemic uncertainty and institutions of power.

For those at our field sites, we can encourage productive, multipartisan conversation and provide a safe space for people to talk and think about political truths. We can help others explore the processes that guide the never-ending remodeling projects that constitute our political realities—and we should, because there will always be another Orbán.

Author’s note: Klára and Lászlóare pseudonyms and their identifying features have been altered.