Article begins

A sense of satisfaction settles in as I sit in the partially constructed herbarium and watch Kipila teach his son how to use the hand lens. Kipila is taking his crash course lessons of botanical identification of plants from the last two weeks and immediately putting them into action by teaching the next generation. He begins by slowly explaining how to adjust the hand lens to the eye and then finding the part of the plant that you want to focus on. His son takes a few minutes to find the distance from the eye not blocked by eyelashes, yet close enough to see details of the plants. We all wait patiently as he figures out the hand lens. Once he can focus on the plant, Kipila begins to describe part of the plant that helps identify the type. I listen as Kipila clearly explains to his son the difference between “alternative arrangement of leaves” and “opposite.” The lesson continues for the next 15 minutes. Once they identify the plant species they are examining, Kipila goes on to describe to his son how the local Maasai have used this plant as a medicine for generations past.

Image description: A young person sits at a table with a spiral-bound book open in front of them. The book shows photos of plants and bears hand-written notes on yellow sticky notes. The person holds a small purple object in one hand and a lens in the other, holding the purple object up to the lens and studying it.

Caption: Teaching youth how to use a hand lens. Kristin Hedges

This community-based participatory research project is called the Olosho Ethnobotany project. Based out of the central division of Narok District in Kenya, the project was launched in June 2017 as a collaboration between Grand Valley State University and Olosho Initiatives. As an applied medical anthropologist, I’ve been working in this community for the past 20 years since I first moved to Narok as a Peace Corps Volunteer in 2000. Joseph ole Kipila is the director of the Olosho Initiatives, and he has have been working with me since my Peace Corps days.

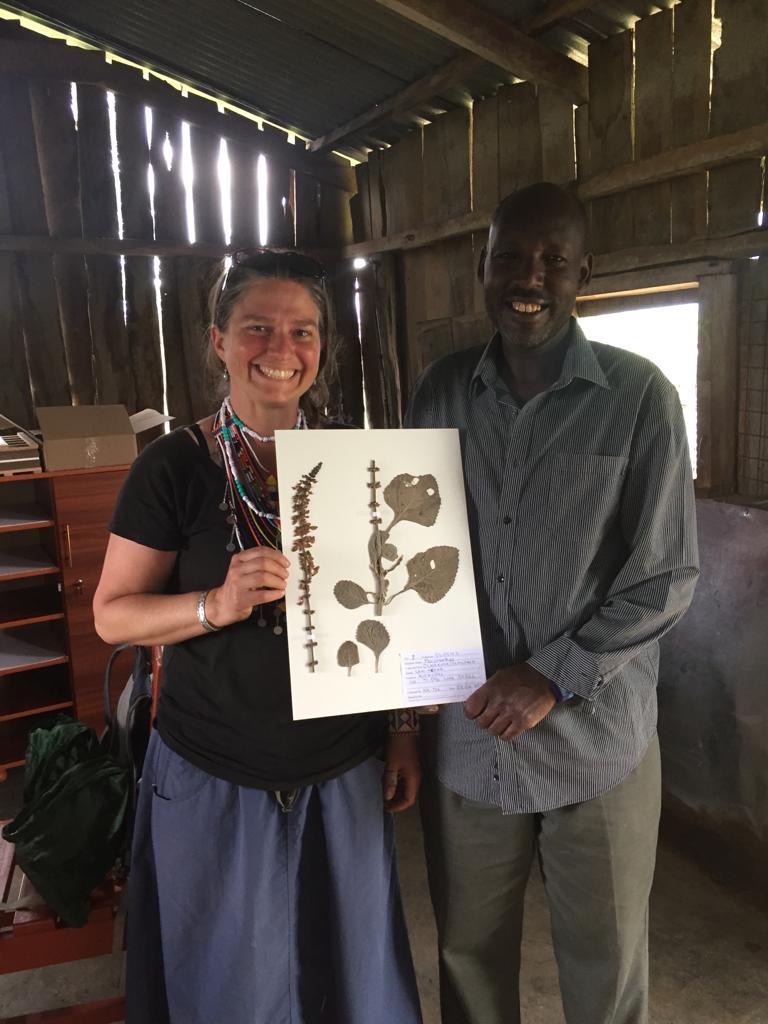

Image Description: A woman in a blue skirt and black top and a man in a gray shirt and tan slacks stand together holding a large white page with green botanical specimens pasted onto it. They stand in a wooden shelter with sunlight shining through the gaps in the wood. Both are smiling.

Caption: First official mounted specimen of the herbarium. Kristin Hedges

Local elders requested assistance documenting traditional medicine of the Purko Maasai. This knowledge has been passed down orally throughout history in this area. As the utilization of traditional medicinal knowledge is reduced, this important cultural resource is in danger. The primary goal of the project is documenting the knowledge for community use. The project has collected botanical data and recorded local use of 30 plants. In addition, the team has conducted 30 ethnographic interviews focused not only on traditional medicine knowledge but also including discussion of preferred healing systems. With a team of interdisciplinary support from Grand Valley State University, I was able to analyze the data collected and produce a small field guide for distribution and to date over 65 copies have been distributed throughout the community in Narok.

Image Description: A book cover with a black background. The photo on the cover is a belt and necklace made of black, yellow, red, and green beads. In the foreground is the title which reads in white: the Olosho Ethnobotany Project and the subtitle which reads in white: Medicinal Plants of the Purko Maasai.

Caption: Cover page of field guide distributed in the community. Kristin Hedges

Ethnographic interviews have led to an interesting finding that could be key to understanding the reduction in use of traditional knowledge by the younger generation. This finding is a discrepancy in the cause of diminishing knowledge. Elders have been reporting that once youth go to formal school, they no longer value Maasai knowledge and don’t want to use the traditional medicine. However, ethnographic interviews in 2018, demonstrated that youth indeed did want to learn about local medicine but felt the elders were refusing to teach them. Qualitative analysis of the data has indicated the generational gap is due to a number of variables, which can all be tied to limited in-situ learning opportunities in the local environment. In the past there was never a required lesson to learn traditional medicine; youth slowly gained the knowledge by being immersed in the local environment (herding, collecting firewood, sent on errands by grandparents, being present while plants were harvested and prepared). Currently, for many Maasai the mode of production is shifting from agropastoral to wage labor jobs in town. As more children head off to boarding school, are raised in town, and have their days occupied by urban errands, the time spent within the local ecology is limited. For this historic cultural resource to survive in modern times encompassed by multiple changes in the local landscape, there is going to have to be a shift in education strategies of traditional medicinal knowledge.

Image Description: A women in tan pants and gray shirt sits on a patterned couch in front of a wooden coffee table. She holds her right hand on her chin as she listens to a mother in a purple shirt holding two children talk.

Caption: Kristin Hedges conducts ethnographic interviews. Kristin Hedges

As a response to this clear need, the Olosho Ethnobotany project launched the next stage in June 2019 by building the local Olosho Herbarium. This herbarium was built in Naisuya village, outside of Narok Town. The goal of this herbarium is to have a place locally to preserve pressed samples of the important medicinal plants and act as a learning center for the community. This stage of the project was funded by GVSU Center for Scholarly and Creative Excellence Collaboration grant. This funding secured the purchase of supplies to open the herbarium (herbarium cabinet, plant presses, mounting materials, hand lens, and so on). Tim Evans, director of the GVSU Herbarium, came to Narok and trained Kipila for the position of director of the Olosho Herbarium. An old corn mill was converted into the facility. The herbarium cabinet was built locally using specific measurements of industry standard cabinets. One of the largest hurdles was figuring out a way to dry the specimens completely before mounting. Since Naisuya is at the foot of the Mau forest, moisture is high in this area. With no running water or electricity, adaptations for drying the materials had to be made. To meet this need, a mud cook stove was designed, created, and adapted to be a drying rack. An official opening of the Olosho Herbarium was held on July 6, 2019. Over 50 community members attended and a blessing ceremony was led by local elders.

Image Description: A group of men gather in a wooden building smiling. One man holds a large white sheet upon which sits a botanical specimen. The sunlight shines through the gaps in the wood.

Caption: Grand opening of the Olosho Herbarium. Kristin Hedges

Kristin Hedges is an assistant professor in the department of anthropology at Grand Valley State University.

Please send column ideas, photos, research updates, and other relevant information for AfAA section news to the contributing editor, Christian Vannier ([email protected]).

Cite as: Hedges, Kristin. 2020. “Documenting Traditional Knowledge through Participatory Research.” Anthropology News website, June 5, 2020. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1414