Article begins

Gabrielle Oliveira is the recipient of the 2019 Council on Anthropology and Education Outstanding Book Award. Here, she recounts findings from the ethnographic study that is the basis of her award-winning book, Motherhood Across Borders: Immigrants and Their Children in Mexico and New York.

Sarah (pseudonym) sat at her kitchen table in her apartment in New York City pounding chicken breasts so she could drench them in egg wash and flour to then fry them. It was her son Agustín’s (13 years old) favorite meal: “He used to ask me to cook this for him every day.” At the time of the interview, Agustín lived in Mexico. Sarah had not seen him in five years, but their communication had never stopped. Sarah never stopped caring for him, even from afar. She explained to me, “this pain of being apart, the only thing is that we have to make it work.” Her youngest son Leo, who was four at the time, sat on her lap: “Is this for me mamá?” “Yes” she replied, looking down to the food she was preparing.

Sarah migrated north not only to look for better opportunities for her son, but also for herself. When she was 16 she became pregnant with Agustín. Her partner left her without ever meeting their son. She relied on her mother, Lupe, to help her. However, as work and life became more difficult, Sarah considered migrating north where she knew some people from her small town in Hidalgo had gone.

The experiences of the mothers I interviewed are only part of the story.

Sarah’s experience of living apart from a child is not unique. In over 60 interviews with migrant women living in New York City whose children stayed behind in Mexico, the main answer to the question of why they decided to migrate to the United States was “to provide for my children” or “to provide a better life to those who stayed.” Mothers justified their absence as service to their offspring: they explained that the reason they had migrated in the first place was to be able to provide for their children. It is important to mention that women, like Sarah, also discussed their own personal narratives of womanhood that were not always attached to their children. Thus, in their portrayals in my book, I tried to not oversimplify women’s stories as only a quest for their children’s education opportunities. Women discussed having to leave abusive relationships, of migration as a way to escape poverty and sometimes as a way to follow a dream of reuniting with or finding a partner. However, the role of education for their children was their primary focus. “If I am able to provide a better education for my son there, I know that he will be better in his life,” Fernanda, 43, told me. “I never abandoned my children in Mexico, I left them,” Claudia, 38, explained. Claudia also explained that leaving is different from abandoning. The first one is temporary and is for the benefit of the children, while the second is conceptualized as a permanent erasure of one’s existence. According to Claudia, Fernanda, and Sarah, the currency of love for their children was to be able to provide them with a better education.

The experiences of the mothers I interviewed are only part of the story. While mothers conceptualized transnational care in the form of securing a better education for their children in Mexico, based on my interviews of their children and their children’s caregivers in Mexico, the children understood that education was precisely the currency of love exchanged with their mothers. In their interviews, children and caregivers actively discussed love and education as being equivalent concepts when interacting with mothers in New York. Dulce, a 14-year-old, explained that if she did well in school her mother would be proud of her and maybe it would lead them to a possible reunification across borders. Her grandmother and caregiver Lupe insisted at home, “the reason your mamá left to go to El Norte was you! To give you a better chance in life, hija. You have to make her proud and show her love.” Thus, the idea to show love through education remained an important aspect of this transnational care structure. Most of the girls interviewed had intense domestic work chores, so the fact that mothers in New York placed such expectations on their academic performance gave them something tangible to work for and provided caregivers and mothers with the constant subject of academic achievement; this context made a difference in terms of the academic achievement of girls in Mexico.

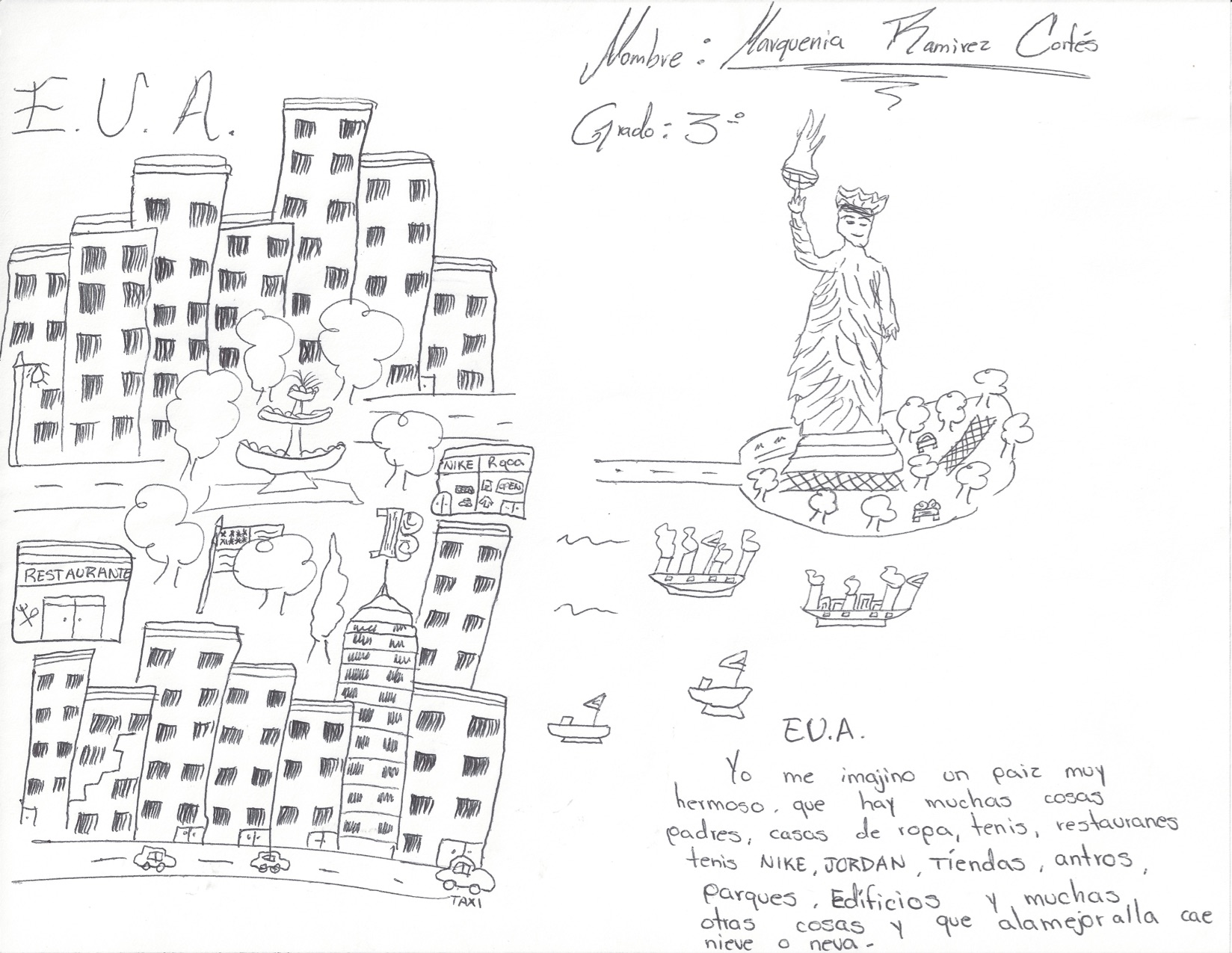

Image description: The letters E.U.A. sit above a cityscape that includes tall buildings, a fountain, trees, and cars. Next to that are boats and a large statue holding a torch in its upraised arm, similar to the Statue of Liberty, as well as the artist’s name and grade. Below the boats is a section of writing that reads “Yo me imajino un pais muy hermoso, que hay muchas cosas padres, casas de ropa, tenis, restauranes tenis NIKE, JORDAN, Tíendas, antros, parques. Edificios y muchas otias cosas y que alamejoralla cae nieva o neva.”

Caption: Drawing of what she imagines the United States to look like, by María, 10. Gabrielle Oliveira

Children and youth carry both the burden and the honor that migration brings. They are dependent on their families and they experience a disjuncture between their symbolic role as beneficiaries of migration and their actual experiences of power vis-à-vis other members of the family. Children and youth in Mexico expected parents to reward them while working in the United States, as exemplified by Tina (age 7) when she opened the gifts her mother Brianna had sent through me. “She is there all this time and all I get is one t-shirt. I thought people went there to get rich!” She continued to explain that she was going to school every day and that she was about to perform in the main dance recital of the town. Tina wanted to be sure her mother appreciated her efforts. After all, the narratives attaching migration, love, and education were predominant within these transnational care constellations. As this narrative circulated across borders, children and parents constantly discussed everyday, mundane issues such as homework, tooth brushing, and neat writing as a way of caring and loving their children.

Children are social actors who make sense of the world they live in. An additional way in which I collected data for my study was through drawings from children. With minimal instruction I asked children to draw what they thought the United States or Mexico looked like and also to draw their families. One example is from a 10-year-old, Maria, whose parents live in the United States. She drew a city with a close resemblance to New York City where her parents live, but she had never been. Maria links material items to the description of the United States. The other pictures show children in Mexico whose mothers live in the United States in a classroom in Mexico. The narratives of doing well in school were attached to getting attention and love from mothers in New York City.

The particular structure where care took place, and which I used as the primary unit of analysis in my study, I call a “transnational care constellation.” Joanna Dreby (2010) first developed the approach of looking for constellations of migrant parents to more accurately describe changes in family dynamics. Keeping in mind Dreby’s work focusing on the parent-child-caregiver constellation, I further developed the concept by putting the mother in the center and focusing on how care crosses transnational terrains and how it influences the different groups of children in Mexico and in New York City. In my book, I propose that these individuals are linked and that the relationships they develop are determined not only by interactions between them and the people they live with, but also by people who are away from them, whom they imagine to be a certain way. A transnational care constellation is a recognizable pattern always composed by the mother (“the one who gave birth”), children (in both countries), and caregivers in Mexico. Using transnational care constellations as my unit of analysis allowed me to shed light not on the entirety of a family system, but on a recognizable pattern of who is involved in caregiving as well as the everyday teaching and educating of children.

Image description: Children sit on their chairs inside a first-grade classroom in the state of Puebla in Mexico. They are wearing a school uniform which is a white shirt and a grey skirt or pants, white socks, and shoes. Six children are visible in the back looking down to their drawings or standing. Four students are the focus of the picture. From left to right: student looking to the side holding a pencil and a pink crayon drawing a picture. Next to her, is another student wearing a uniform, but also wearing a striped sweater on top. Next to her, a student is trying to get crayons out of the box in order to complete the drawing. Finally, there is a fourth student who is working on finishing their drawing with paper in front of them and holding crayons. There are two backpacks in the picture.

Caption: Photograph of children at a primary school in Puebla, Mexico. Gabrielle Oliveira

In my book I discuss in detail the ways in which these transnational constellations are organized and how parenting from afar takes place. I grounded the study in narratives from children, mothers and caregivers as I prioritized relationships over physical location. As policies continue to undermine, attack, and destabilize immigrant families in the United States, at the border, in Mexico, and elsewhere in the world, it is important to understand how relationships, education expectations, love, and care happen across transnational terrains. While current draconian immigration policies continue to be implemented, immigrant mothers and parents are making the best possible decisions they can for their children. Findings in the book shed light on the ways immigrant women mother even when physically separated from their children.

Gabrielle Oliveira is assistant professor of foundations of education at the Lynch School of Education and Human Development at Boston College. She received her bachelor’s degree in her native Brazil and earned her master’s and doctoral degrees from Teachers College and Columbia University. She is currently a postdoc fellow with the NAEd/Spencer Foundation.

Cathy Amanti and Patricia D. López are contributing editors for the Council on Anthropology and Education’s section column. If you would like to contribute, contact us at [email protected] and/or [email protected].

Cite as: Oliveira, Gabrielle. 2020. “Education as a Currency of Love.” Anthropology News website, May 29, 2020. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1410