Article begins

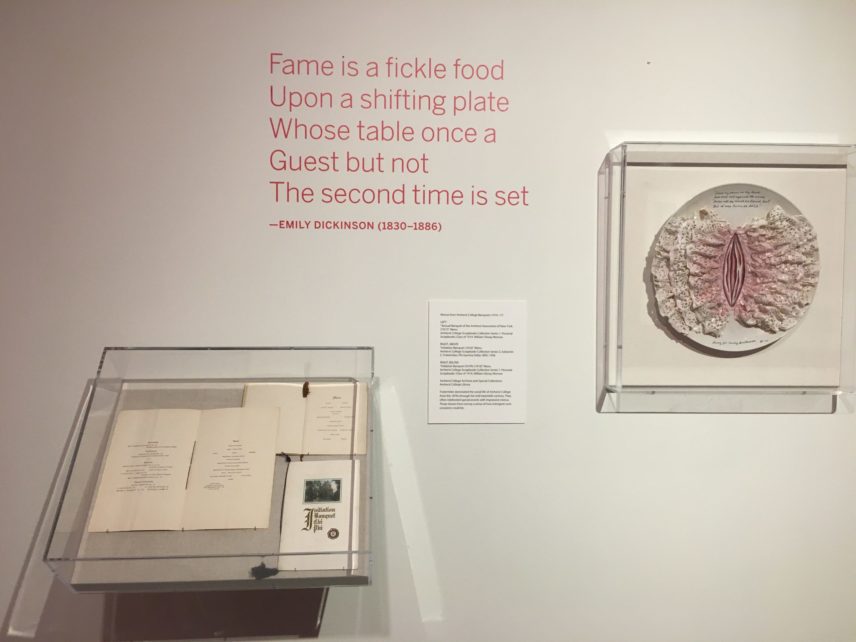

Embodied Taste opened in December 2019 at the Mead Art Museum on the campus of Amherst College. The first collaborative student-curated exhibition to be installed at the Mead, Embodied Taste was the culmination of an upper division anthropology course that centered student voices, project-based learning, and public scholarship. The exhibit invites visitors to enter a diverse, multisensory space that decenters privileged narratives as it explores the ways food moves through our bodies and our worlds. Following positive reviews, its run was extended and the exhibit selected as a pilot virtual exhibition, which is currently on view.

All of the objects displayed in the exhibit had to come from the collections of the Mead Art Museum or the special archives at the college. Unlike other exhibitions, we did not have the funding or the time to request outside loans. In preparation, we sorted the collection according to a variety of themes all related to the category of food to ensure the course readings and syllabus made sense. Emily did a pre-sort of the collections, finding about 100 objects that might be used. These were broken down into smaller groupings, paired with complementary readings, and reviewed by student curators during the first four weeks of the course.

After the students had selected their overarching concept and narrowed the objects to be displayed, we shared some startling statistics. Of their draft list that contained 33 works, most were created by white, non-Hispanic male artists, with only two Haitian artists, one African American artist, and four women artists included. As a class we discussed the implications of their choices and how to address them. Students changed some of the artwork, adding previously overlooked works by contemporary African American artist Lorna Simpson, among others. They decided to find more global food stories, curating a video loop to emphasize women and labor in the kitchen. And, they felt strongly that the most prominent piece of artwork in the exhibition should not be Frans Snyder’s Larder with Servant, as had been suggested by a guest speaker, but Serge Hollerbach’s Two Girls with Soft Drinks. With these adjustments, they hoped to avoid reinforcing a dominant white masculine Eurocentrism already present in the Mead’s collections and in museums more generally.

Many students felt that museum exhibitions were unwelcoming and elitist and wanted to create something that would be appealing to a wider audience and to themselves. We began the course reading Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation and Stephen Greenblatt’s Resonance and Wonder. Inspired by these and other readings on exhibition design and critical food theory, students decided to create a space that was multimodal, sensorial, and welcoming. In the first room of the gallery, two students recorded audio of people eating together and alone, which were shared at two listening stations. The audio recordings also included food-related poetry by graduating senior Sommer Hayes and feminist author Minnie Bruce Pratt. In the second room, the group made an interactive recipe and memory station. At a simple table, designed to evoke a dining counter, visitors viewed recipes left by others and shared their own. There was also a “smelling station” comprising locally sourced food aromas. The paint colors, Benjamin Moore “white flour” and “cherries jubilee,” were intentionally chosen to support the mood and thematic of the exhibit. A purchased neon sign that read “Eat!” was playfully hung at the gallery’s entrance as a way to add humorous vibrancy and enliven what are often somber art museum spaces.

The course was challenging. There was not nearly enough time. But the excitement of sharing something publically was incredibly motivating. Without question, the exhibit was successful because of the students’ commitment to one another and to a respectful exploration of our collective imaginings, desires, and talents. The exhibit opened on the last day of class. Families and friends joined us to celebrate. Since then, several students have graduated and the pandemic has complicated museum visits. Still, their work continues to impact the community: The space has been used for K–12 and college class visits, dance improvisation, and research by Folger Institute Collection Fellows. Most recently, it seeded a partnership with Amherst Regional Public Schools for their fourth grade curriculum, connecting family recipes, farms, oral history, and portraiture.

We would like to acknowledge and thank all the student curators: Abner Aldarondo, Violet Bain, Charissa Doerr, Michael Gibson, Anaid Garcia, Mollie Hartenstein, Charity Hilliman, Sabrina Lin, Sara Near, Sydney Nelson, Jiwoo Park, Parker Richardson, Estevan Velez, Ingrid Shu, Kalley Wasson, and D. J. Williams.