Article begins

In her drawing of her parents’ hometown in El Salvador, 11-year-old Jessica drew a spider (because “there’s so many spiders there”), an avocado tree, a lemon tree, a church, the flag of El Salvador, and a plate of pupusas with salsa and curtido (“because that’s all we eat there!”). She said she had helped plant the lemon tree, and she showed me a clothesline extending from the lemon tree to the avocado tree that her grandmother had put up for her to hang her clothes. Like most of the children in our after-school program, Jessica had an intimate familiarity with her parents’ hometown, and she labeled her drawing not only with “El Salvador,” but also “Chalatenango” (the province) and “San Rafael” (the municipality). When her mentor asked her how she felt when she was there, Jessica said she drew the church because they always go to church and that church makes her “feel at home.”

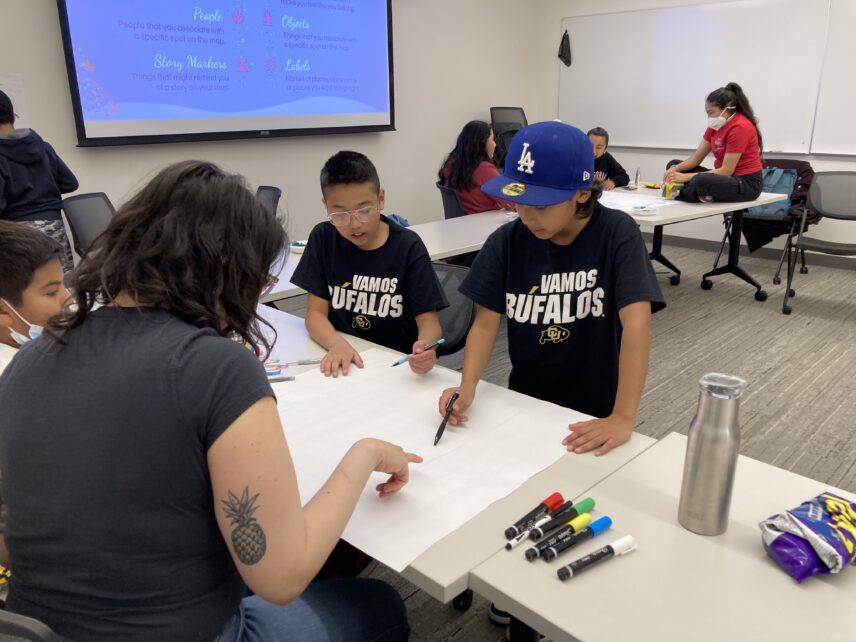

Jessica’s drawing illustrates the many sides of home that we explore with bilingual fifth graders in an after-school cultural mentoring program at University of Colorado (CU), Boulder, where spiders show up alongside avocado trees, and memories of food and family togetherness alongside stories of state violence. For the past three years, CU graduate and undergraduate students in education and ethnic studies working with me, have been holding a rare space for reflecting on cultural identity, migration, and belonging, and what it means to be Latinx or transnational in Boulder. In our program, hometowns in Chalatenango, El Salvador; Zacatecas, Durango, and Chihuahua, Mexico; in Honduras, Chile and, Paraguay, come alive alongside family stories of migration, staying connected across borders, and trying to get ahead in Boulder. Inspired in part by the Adelante program founded by Dolores Delgado-Bernal and Enrique Alemán at the University of Utah, our program was conceived as a partnership between underrepresented students at CU (the mentors) and predominantly Latinx fifth-graders at University Hill Elementary School (the mentees), to collectively explore their cultural identities and what Tara J. Yosso calls their “community cultural wealth.” In weekly after-school sessions, CU mentors design activities to provoke reflection and dialogue around cultural identity, explore the complexities of transnational experiences, and build community in the borderlands. The resulting interactions reveal a wealth of cultural knowledge, skills, and abilities that are often not visible to the public or in daily life in US schools.

The cultural mentoring program becomes a way of ethnographically documenting young people’s transnational cultural knowledge that serves the purposes of community building and critical consciousness-raising between mentors and mentees, while also creating an archive of local Latinx histories that can be used by K-12 teachers. In fall 2021, two doctoral student researchers on the project, Jackie Bristol and Daniel Garzón, and myself produced a report on the program’s first two years, Bilingual in Boulder, highlighting students’ cultural knowledge around four salient themes: transnational belongings, surveillance and criminalization of immigrants in Boulder, economic understanding, and shared cultural values and practices. The report, published online in collaboration with the Latino History Project, documents the shared learning as mentors and mentees explored their family histories, transnational connections, and their complex identities. Fifth-grade mentees shared about what it’s like to be coming of age as bilingual children of immigrants in Boulder, where Spanish is nurtured in their dual language school but sometimes disparaged in public. As trusting relationships formed, students also opened up about their experiences with racism, fear of the police in their own community, and the militarized border. In school-wide professional developments, my colleague and research partner Deb Palmer shared the report with Uni Hill teachers, leading them in discussions on their students’ transnational lives. It is our hope that by fostering continuous collective inquiry into students’ lived experiences, the program nurtures dynamic connections between classroom instruction and students’ communities, reflecting an engaged anthropology of education that can counter deficit discourses about Latinx students and communities. This addresses the challenges of the “Funds of Knowledge” work pioneered by Norma González and colleagues, which sought to validate the social and cultural capital of minoritized communities for teaching without falling prey to simplified and stereotypic views of students’ “home cultures.”

One way we do this is through the creation of a new kind of home in the university, where mentors and mentees from minoritized communities accompany each other in the mutual exploration of shared cultural and political realities. Enrique Sepúlveda defines acompañamiento as “a practice of solidarity, of relationship and community building, of claiming space and bearing witness in an unjust, dehumanizing and fragmented world.” As a borderlands pedagogy, acompañamiento strengthens our ability to embrace the complexity, contradiction, and ambiguity of life between worlds, engaging border subjects in the effort to dismantle simplified, stereotypic, and static views of their own communities and identify practices, experiences, and historically constructed knowledge. In a credit-bearing class, CU mentors reflect on their own identities and experiences in the context of readings on borderlands theory, cultural organizing, and culturally sustaining pedagogies, and then design activities for the after-school program based on their own reflection. This model of collective inquiry and exploration with our fifth-grade mentees ensures that “culture” is never reified or essentialized, but always explored through lived experience.

Mentors express that the sense of community created through the sharing of experiences is as transformative as the knowledge produced. One graduating senior reflected, “The most rewarding part of mentoring was getting the opportunity to sustain a humanizing space in which we could all be ourselves and be vulnerable with one another.” Another mentor explained, “School curriculums don’t do much to reinforce or incorporate our cultural backgrounds and instead promote assimilation. I think cultural mentoring is a crucial counterspace for interrupting that process by placing cultural identity on the foreground.” In the context of this counterspace, we could excavate the multidimensional, fluid, dynamic, and messy realities of transnational communities.

Excavating hidden transnational knowledge

While most of the fifth-grade mentees are US-born, they are transnational, with family ties extending across borders to hometown communities in Mexico and other countries of Latin America. Many of them have one or more undocumented parent working in the informal and service economies in Boulder: in landscaping, restaurants, housecleaning, and food vending. Several of the families in each cohort came from the states of Zacatecas and Durango in central Mexico, reflecting long-established migration routes from Mexico to Boulder County going back to the 1910s. What’s more, many of the families were from the same hometowns in Zacatecas, and students often named these towns and felt connected to them. For example, one student explained, “Even though I wasn’t born there, I feel connected to it, because my parents were born there.” Another student described herself as “Kind of American and Chilean because I was born here [in the United States], but I represent myself as Chilean,” because “my soul is from Chile.”

In small groups, mentors engaged mentees in conversations about identity and modeled transnational attachments by explaining their own connections to their parents’ hometowns and their own complex identities. In one session, after watching excerpts of the film Abrazos about transnational migration and family separation, two mentors read aloud letters they had written to their grandmothers, before inviting the children to write or record their own greetings to faraway loved ones. One mentor’s letter recalled the smell of coffee and handmade tortillas in mornings on the rancho in Mexico, and thanked her grandmother for teaching her about “love, respect, wisdom, and courage” as well as “how to shuck corn and announce the passing of the cows” (my translation from Spanish). In the activity following this, 11-year-old Oscar was bent intently over his work. His letter to his grandmother “mimi” in Mexico was an illustrated comic strip of memories and gratitude: for hugs, his grandmother’s cooking, buying him treats from a street vendor, bringing him chocolate milk and toast, and letting him go out whenever he wanted. Oscar frequently got into trouble at school and according to his mentor, had been suspended. His letter to his grandmother expressed a side of himself not often seen at school—a fuller picture of himself that was in contrast to his experiences of disciplinary action. In our mentor meetings, we reflect on how telling our stories, within communities of trusted acompañantes, can help us recover parts of ourselves that are hidden in daily life in US institutions—sometimes forgotten even to ourselves—thereby restoring us to full, multidimensional humanity.

The search for the fullness of our experience also means not romanticizing students’ homeland experiences or home “cultures.” As we nurtured and documented students’ growing critical consciousness and rich cultural resources in transnational families, we also came upon sobering realities that challenged our responses. For example, one student, Edwin, told of a trip to El Salvador with his dad, who had been in the army. He proudly described how his dad took him to visit military friends who showed Edwin how to hold a gun. In a city still recovering from a mass shooting in a local supermarket, this knowledge was unsettling. In our mentor meeting afterwards, I shared how, given what I knew about the Salvadoran Army’s human rights violations during the war, this announcement of Edwin’s scared me, and I hadn’t known how to respond. Mentors shared their own family experiences with guns. As we discussed how to validate students’ knowledge without glorifying or uncritically endorsing it, we accompanied each other in trying to make sense of complex realities. As mentors and teachers in the borderlands, we realize that we don’t always have the answers. The importance of acompañamiento lies in raising participants’ critical consciousness about the structural realities that affect our lives—including multiple forms of violence—and honoring the cultural resources that have allowed our families to survive and thrive across generations and borders.

Author’s note: All children’s names are pseudonyms. The cultural mentoring program is supported by the CU Boulder Outreach Awards Committee.