Article begins

Tensions began to arise a month into the first year of The LGBTQ+ Intergenerational Dialogue Project when Anthony, a 72-year-old bisexual man, questioned the validity of transgender identities in a group dialogue. Young people’s “obsession with flipping back and forth” between genders makes no sense, he said. Our younger participants were swift to respond. They turned their bodies away from the man as he spoke, looking at each other in disbelief. Several elder participants visibly tensed as they glanced at the “youngers” with concern. Anthony had already sparked controversy the previous week when he flirted with a transmasculine graduate student over dinner, saying he thought he “was a real man” when they first met.

After the meeting, a circle of students approached us to discuss what action should be taken to ensure that all participants would “feel safe” in future dialogues. The next day, we heard from a transgender colleague who, after speaking with a student about the incident, recommended that we require our older participants to complete a Transgender 101 training before engaging with the younger ones. Our students shouldn’t have to take on the emotional labor, our colleague said, of having to explain themselves to others.

For many years, we (a lesbian anthropologist and a gay philosopher) have been struck by the disconnect of our LGBTQ+ college students from the LGBTQ+ histories, cultures, and people who came before them. At the same time, we have learned from LGBTQ+ older adults (60+) how forgotten and isolated they feel from LGBTQ+ communities they helped to create. In 2019, we partnered with a Chicago-based LGBTQ+ community center to launch an intergenerational pedagogical project that brings together racially, socioeconomically, spiritually, and gender diverse cohorts of LGBTQ+ youth and elders for dialogues, creative work, and shared dinners.

As the project organizers, we learned early on that our attempt at a queer embodied intergenerational pedagogy involved a good deal of risk. While we expected that discussions around certain topics would be challenging due to the disparate viewpoints and life experiences of our participants, we have been surprised at the energy that many devote to avoiding emotional interactions altogether. Both older and younger generations fear hurting each other, or getting hurt, when talking about things they see differently. These concerns feel especially weighty in an intergenerational gathering of marginalized folks who continually express excitement at finding each other, being together, creating a community, and becoming “family.”

Generating queers

There is, as Catherine Lugg illustrated, a long history of queer erasure in US public schools. Young people in the United States have long been discouraged from non-normative gender and sexuality by dominant cultural and educational systems that work to ensure compulsory heterosexuality and heterogenderism. LGBTQ+ history is seldom taught in K–12 curricula, and young people are often blocked from contact with LGBTQ+ adults. The majority of LGBTQ+ youth are still coming of age having never met another LGBTQ+ person and feeling as if they’re the only one in their communities.

Ample research has documented the vulnerability of both LGBTQ+ youth and older adults due to social isolation. GLSEN’s national survey on school climate has documented these realities for students since 1999, while Soon Kyu Choi and Ilan H. Meyer’s review of research documents these realities for LGBTQ+ elders. Both populations are at much higher risk for depression and suicidal ideation, physical and sexual assault, homelessness, and alcohol and drug dependence than their heterosexual and cisgender peers. Today’s older LGBTQ+ adults, members of the first “out” generation in the United States whose lifetimes have coincided with dramatic legal and cultural shifts in LGBTQ+ acceptance, are making the painful decision to go back in “the closet” as they lose the ability to live independently and enter nursing homes.

Through The LGBTQ+ Intergenerational Dialogue Project, we explore how education might be harnessed to cultivate, rather than suppress, queer people and community. Through shared meals and biweekly themed dialogues on topics the group collectively selects (such as gender politics, HIV/AIDS, family, sex, and activism), our participants engage queer studies as a hybrid experience that vacillates between the academy and the community. Storytelling has become a focus, and we often spend the first hour of each meeting listening to participants of varying ages talk about their personal experiences with topics and moments important to LGBTQ+ history. This allows participants to create a new form of queer studies informed by embodied histories and their complex interactions.

Embodied intergenerational pedagogy

Sometimes we have felt frustrated with our participants’ avoidance of difficult conversations and unsure of our role as teachers and facilitators. Several elders and students have expressed similar frustration to us privately, lamenting the loss of potential “teaching moments” when we, as a community, shy away from unpacking tense moments together. Differing understandings of gender have proven to be the most complicated issue to navigate intergenerationally. Although we spoke with many participants about Anthony’s statement and actions, we never, as a group, discussed them or their possible sociohistorical context. When we tried to broach the topic, it seemed too volatile a situation to push further. Eventually, Anthony and the graduate student left the project. Was this a failure on our part? Or was it part and parcel of an intergenerational educational project?

Embodied pedagogy, especially among such a diverse group of people, feels to us like collaborative ethnography in the best and most challenging ways. Participants conduct participant observation within a community they are working to understand. It is physical, emotional, and sensory work centered around personal interaction. While our official themed dialogues are the heart of the project, we have learned as much from our informal conversations and just being physically together in different settings (over dinner, visiting each other’s homes, and outings to a nearby Karaoke bar). As facilitators, we have realized the importance of flexibility and letting things develop organically. We see friction between members as generative, but still grapple with the fine line between constructive discomfort and potential harm. Wendy, a transfeminine father in her early sixties, once observed that the whole thing feels a bit like a wonderful “social experiment.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic suddenly prevented us from meeting in person, it seemed that the project might need to be put on hold. How, after all, can embodied pedagogy—especially one centered on personal connection—happen over Zoom? Ironically, we found that Zoom offered us a way to see, hear, and talk with each other more often, and in a more intimate way than we had previously experienced. The group decided to increase the frequency of our meetings to weekly, even after many of the students had graduated.

The importance of sustained contact over time has become clear. Time has allowed relationships to build, and empathy to grow. It makes space for the ebbs and flows of nonlinear progress and shifting perspectives. More than a year into the project, Lorenzo, a 75-year-old HIV+ gay man, surprised many of us when he declared that he was “okay with the word queer.” In previous conversations, Lorenzo had been a vocal opponent of the use of “queer” as a signifier to describe our group. “All my life,” he would say, “they called me sissy, faggot, queer. You could get killed for it.” Lorenzo’s strong response to the term was eye-opening for our students. They had not fully realized its painful history for LGBTQ+ generations before them. Lorenzo, in turn, credited the young people in our group for his eventual change of heart: “I see for them it’s a positive thing.”

Generation liberation

In August 2020, we welcomed a new cohort of students and elders to the second year of the project. In our first meeting, we discussed the challenges (as well as joys) that had arisen in the first year. A student proposed that we strive for what social justice educators Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens call a “brave space” rather than a “safe” one, and participants worked together to establish community guidelines for navigating sensitive conversations. We cotaught a new course, entitled Generating Queers, for students involved in the project. The class alternated between seminars and intergenerational dialogues. The addition of seminar meetings for students offered a better framework for grappling with the affectiveness of an embodied intergenerational pedagogy. Seminars provided a space in which to reflect on the dialogues, and learn through assigned readings, documentaries, and podcasts about LGBTQ+ histories. Still, students’ resistance to emotional labor (as they termed it) became a recurring theme in our class discussions.

Halfway through the fall semester, the intergenerational group watched Gen Silent, a documentary that follows six LGBTQ+ seniors in Boston as they struggle to safely navigate aging. Watching the film proved to be a watershed moment for the participants, both young and old. In our seminar meeting, students described their visceral reactions to the film. Many cried during scenes that depicted a transgender woman dying alone after being abandoned by her family and were shaken by the harsh realities that others encountered. The following week’s intergenerational dialogue on LGBTQ+ aging felt different than previous ones. The film offered a pathway toward empathy, mutual respect, and patience between generations. It also sparked the group’s decision to focus their collaborative creative work for the students’ final projects on moments of “queer joy” in the midst of pain and hardship. In small groups that met regularly for the second half of the semester, youngers and elders together plumbed their life stories for moments of uniquely queer joy.

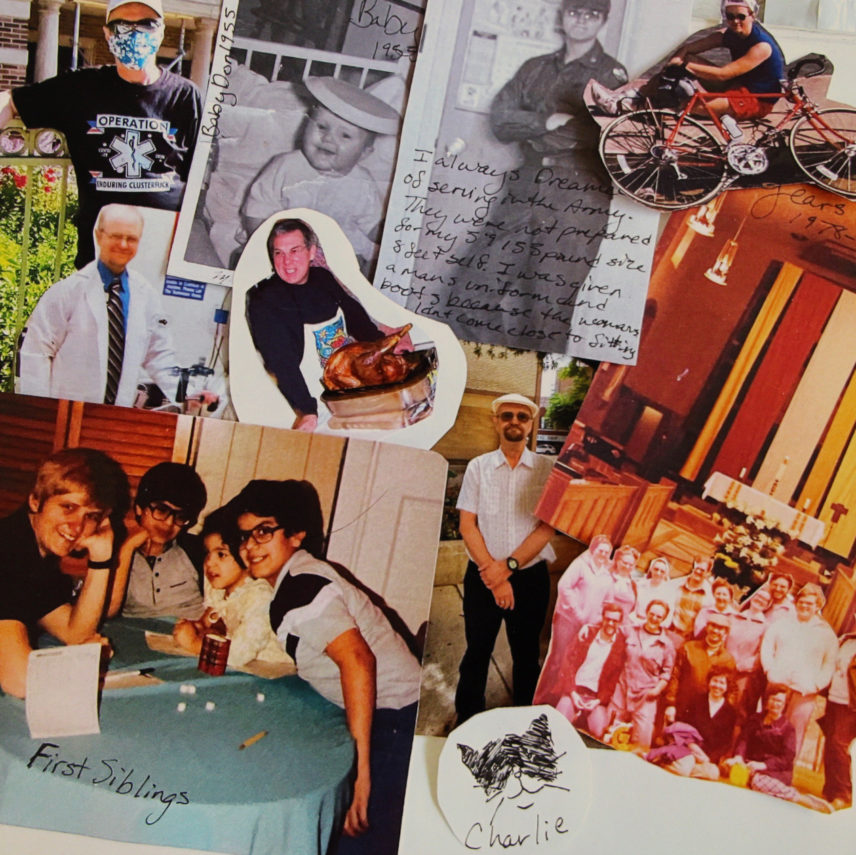

The process of working through queer joy proved to simultaneously exciting, frustrating, and anxiety-producing as participants tried to find shared threads of joy and determine what queer joy even meant. Ted, a 66-year-old man who had been assigned female at birth, transitioned in the 1970s, and endured multiple hospitalizations in psychiatric wards, surprised his group by revealing that he had no queer joy. He did not know how he could contribute to the project. The group’s ensuing discussion resulted in a book in which participants revisited, with a sense of gentleness, “the wonderful, the awkward, and the sometimes painful” moments in their journeys to queerness. In the book, Ted’s collage of photographs depicts memories such as wearing a man’s uniform and boots as a college student in Army ROTC and the warmth of hanging out with his chosen family. The process of uncovering these moments in Ted’s journey is represented through a movable translucent sheet that covers the collage with handwritten notes and doodles. Ted’s typed notes on the joy he finds within these memories accompany the piece.

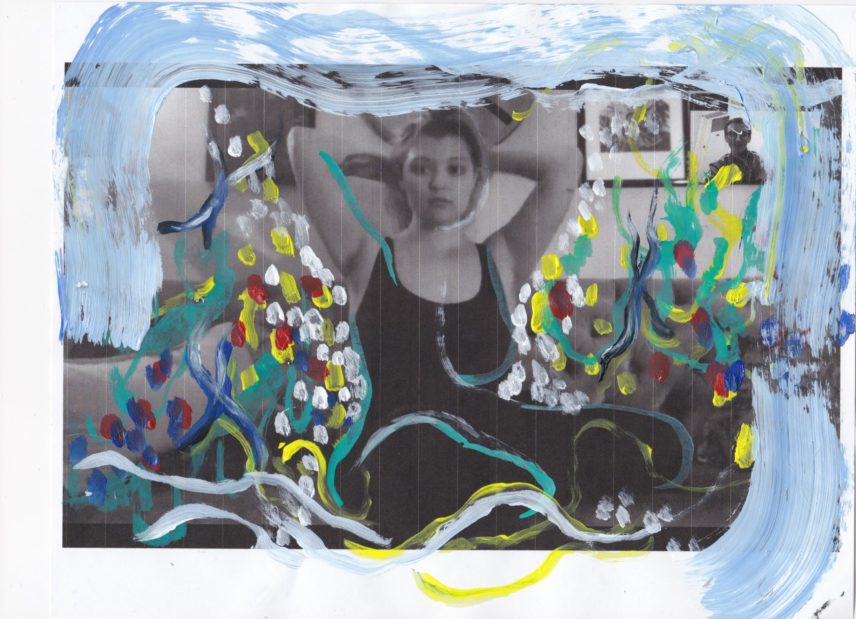

Other small groups ended up producing a blog on queer fashion as a tool for empowerment and communication with fellow queers; a map of a virtual road trip that celebrates places where the authors found “communities that understand us”; a sound piece of spoken word and storytelling set to field recordings and ambient soundscapes; and an anthology and visual essay which focuses on “love in various forms: familial, romantic, crushes, from inside and outside the closet.” The anthology and visual essay weaves first-person narrative and interviews with photographs that have been illustrated to convey the personalities of the narrators. Juliet tells stories of falling in love instantly, and expressing a fierce form of queer love to her siblings.

As participants shared their finished projects with each other, we noticed some emerging themes. All of the projects revolved around storytelling. Participants found joy in the personal—both reflecting on and sharing their own personal experiences, and gaining access to others’ lived experience. Many stories focused on joy in finding one’s people and one’s place, being accepted, and feeling seen for who one is. In seemingly tiny and fleeting moments, such as Veda holding hands with a partner in their dad’s pickup truck during a hometown visit, folks of different ages and backgrounds found validation, love, pride, and a feeling of freedom. The projects realize the sheer joy and lightness felt in these moments as distinctly queer because of their relationship to the pain and loneliness that often permeates LGBTQ+ existence. Both youngers and elders found joy in embracing the magic and wonder of being LGBTQ+ amid the challenges it presents.

As our fall course came to an end, a student wondered out loud how this type of work could be continued out in the “real world.” He, along with many of his elder and younger peers, sensed a need to expand the work of our project beyond its current members and boundaries. In our dialogues together, we have pondered how our project model could be modified for various settings. A colleague at a neighboring public research university recently joined our project, providing the dialogues an opportunity to not only connect students across universities, but also expand our work with additional nonprofit organizations that serve elders in other geographic areas of the city. Veda, who returned to their small hometown after graduation, is pondering how an intergenerational dialogue project could work for queer people in nonurban settings. We applied for a grant to support the group’s production of brief animated films, photo essays, and zines on LGBTQ+ history, from an embodied intergenerational perspective, for use in Illinois public schools’ newly mandated LGBTQ+-inclusive curriculum.

This project has taught us to think about intergenerational cultural transmission in more expansive ways. We often think of older generations as the keepers of knowledge who pass down vital traditions, history, and culture to their descendants. While the older participants in our project embrace their newfound role as elders, they and their younger peers have made it clear that intergenerational pedagogy is not unidirectional, nor is it simply a transfer of information. Intergenerational exchange is generative. It is through personal interaction between folks whose lived experiences span 70 years of dramatic cultural, political, and legal shifts in LGBTQ+ history in the United States that new knowledge, community, and subjectivities are being produced.

At some point during the fall semester, students in our class began to ebulliently acclaim at the end of our meetings that they “feel gay!” In post-class feedback, several students reported versions of what one student described as “a sense of security in my place in the LGBTQ+ community.” This led us to wonder, Can “feel gay” be a learning outcome for an embodied intergenerational queer pedagogy? Is this one way in which the project generates queers? We see, in the joy and heartache that we and our participants find in being LGBTQ+ together, the possibilities of what educational philosopher Gert J. J. Biesta has called “the beautiful risk of education.” Our website, recently launched with the collectively chosen domain name Generation Liberation, embraces this risk in publicly sharing our images, identities, tensions, and work in an effort to see what happens when people who usually would never interact come together.

We use pseudonyms in this essay for all project participants. However, participants have chosen to be identifiable on our website. All participants featured in the images in this essay have given their permission for the images to be published.