Article begins

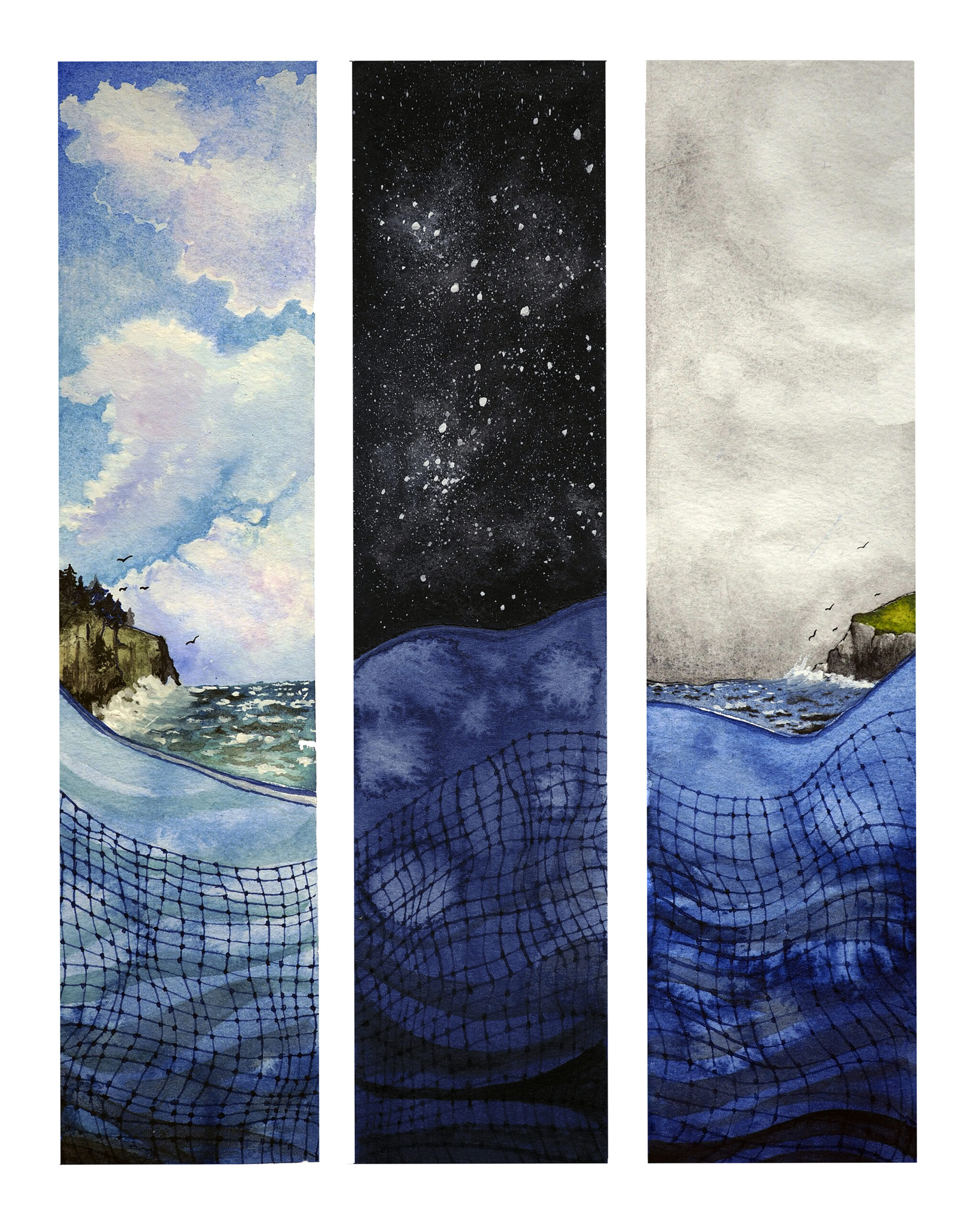

Beneath the waves of the Atlantic, it’s hard to tell the when of anything. Towards the ground the water is cobalt, deepening to black. Colors are paler towards the surface, where muted sunlight reflects in the hazy gray-blue of silt and particulate. We are in the deep water of eastern Canada, hovering over the marine shelf that extends off the coast of Newfoundland.

There is a fishing net hanging like a curtain, anchorless, on the edge of this shelf with no fisherman in sight. The net shimmers dully. The nearly translucent monofilament mesh catches the dim light that fades more with the depth than with the day. It is four hundred feet long. It is about the size of a football field, almost 30 feet longer than the world’s tallest redwood tree is high, and almost three times the height of the Statue of Liberty. This particular net is a gillnet, which means that it ensnares fish by their gills, and it is held horizontal in the heliotrope water by a series of floats along the upper edge and weights along the bottom. It belonged to a Newfoundland fisherman named Denis Greene, until turbulent seas in the late spring of 1989 detached the net from the moorings that Denis had carefully set. Now it drifts south with the cold water of the Labrador Current, looming like a strange mist on the easternmost edge of the North American continent.

Fishermen in Newfoundland and elsewhere call these lost plastic nets ghost nets, and the nets are not just in Newfoundland. Almost a thousand of them have been recovered off the coast of Washington state with tens of thousands of marine animals tangled in their mesh. And they’re not just in the Americas. Ghost nets make up at least 10 percent of marine trash, and almost half the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. There are nets in the water that have already fished for 20 years. Some might roam the oceans for six more centuries.

When Denis Greene was born, Newfoundland was still a country. It was 1936, the middle of the Great Depression, when many people in his hometown depended on the government dole of flour, molasses, and fatback pork to make it through winter. Throughout his childhood, Denis would get up at three or four o’clock in the morning to jig squid for his grandfather to use as bait. After school, the two of them would fish for cod, hauling long lines of hooks and silver-gilled beings from the Atlantic. Denis was 13 years old when Newfoundland became part of Canada, and 28 years old when his hometown was connected to the electrical grid.

Denis fished with his grandfather until he turned 21 and left home to see more of the world. He met his wife in Nova Scotia and worked there as a roofer until 1978, when he returned home to be a fisherman once more. He “couldn’t stay away from work on the water any longer than that,” he said, and he described the desire to come home to work on the sea like a longing or a calling, something he couldn’t deny. But by that time, he’d lived in Nova Scotia for as long as he’d lived in Newfoundland, and when he got home he found that the fishery was altogether different. Instead of hooks and lines or cod traps or smaller nets made from cotton and hemp, fishermen in Newfoundland had started using factory-produced sheets of nylon netting that hang suspended in the water column, practically invisible to the cod they’re used to catch. In 1979, Denis and his cousin went in together on buying a fishing boat. They named their boat The Future.

At first, Denis took up the new fishing practice without question. The volume of cod he could catch with these nets was huge compared to the labor and time required for the relatively small number he had caught with his grandfather. Besides, it would have been impractical to refuse the nets that everyone was using, which had been introduced and subsidized by the government.

But then the nets started getting lost. Sometimes they weren’t tied down correctly and came detached in the currents. Sometimes the moorings couldn’t hold in rough water. Sometimes there seemed to be no explanation; the net was just gone. And then some of the nets started to reappear. They snagged in boat propellers, they snaked around crab pots and lobster buoys, they snared near the shore, always full of rotting fish. The nets, once lost, continued to drift with the currents, fishing by themselves.

Denis fished for cod from 1978 until 1992, the year Canada closed the depleted cod fishery and 30,000 people in Newfoundland and Labrador lost their livelihoods. Over those 13 years, Denis lost between 15 and 20 industrial-sized plastic fishing nets. He says he didn’t know what to do. Not only were nets expensive to buy and certainly expensive to lose, there was also something deeply wrong about beautiful fish going to waste, something deeply troubling about fish being killed by something he had lost. Cod was the living creature that had defined and sustained him almost his entire life. But what else could he do? He was a fisherman, and this is how fish were being caught. Refusing the huge plastic nets could have meant unemployment, bankruptcy. Denis went looking for his nets. He came up with two, maybe three, but he doubts they were his to begin with.

By 1965, the lost nets the provincial government subsidized fishermen to replace numbered 30,000—which was also the number of people in Newfoundland and Labrador that would lose their livelihoods 27 years later when the exhausted fishery closed.

I interview Denis in 2018, after nearly a year of delighting in the fresh tiffins (traditional fried dough) and fishcakes he often shares with his neighbors. We sit at his kitchen table in the one-story bungalow he downsized from a two-story wooden house he could no longer afford to heat after the cod collapse, and we talk over the warm hiss of fish that his wife pan-fries in scrunchions (pork fat) for our supper. He tells me he thinks that the nets were the ruination of the Newfoundland cod fishery. There is wonder in the words he repeats: “They’re out there still; they’ll never, ever rot.” They’re still out on the Banks, right on the edge of the deep water, catching fish now and forever. “It’s a crime,” he says. He says this like a confession. He says this like he is angry, but at whom or with what it is difficult to tell. Denis is 82, and he says that the nets he lost never really leave his mind. They’re still fishing the currents without him.

The new plastic nets that Denis had to use when he reentered the fishery were part of a post-war government effort to modernize rural Newfoundland and Labrador through industrial development programs aimed at increasing economic production. Economic precarity was a primary reason why Newfoundland voted by a slim majority to become part of Canada in 1949. Newfoundland’s hundreds of small rural fishing communities, like the one Denis grew up in, offered both a problem and an opportunity for economic development. Government agencies began to reach for technologies and materials honed during the World Wars, including nylon, to help “drag” Newfoundland fishing communities “kicking and screaming into the twentieth century,” as Joey Smallwood, the province’s first premier, allegedly said (although the origins of this quote, widely repeated by fishermen and scholars, are somewhat opaque).

The first provincial attempts at modernizing the fishery with plastic were already underway the year Denis left home for the first time. I research this period of fishing history among the boxes of the Newfoundland and Labrador provincial archives, riffling through reports and old newspapers and opening files that make me sneeze with dust. I learn that during 1954 and 1955, when Denis was roofing houses in Nova Scotia, the Newfoundland Department of Fisheries was undertaking a project that introduced synthetic fishing gear into Inuit communities in Labrador on an “experimental” basis. One of the four stated goals of the project, organized by the Labrador Fisheries Development Committee, was to “increase the productivity of the natives,” revealing the program’s colonial undertow. When it was determined that nylon nets used in the Labrador study retained more fish than nonsynthetic nets, the provincial Department of Fisheries sought support from the Industrial Development Branch of the federal Department of Fisheries to design and distribute nylon fishing gear in Newfoundland fisheries more broadly. After corresponding with fisheries ministers and organizations from Norway, Iceland, the United Kingdom, and Japan, federal and provincial fisheries departments determined that industrial-sized gillnets made from nylon netting had great potential to increase the landing volume and efficiency of Newfoundland cod.

In 1960, the Newfoundland Department of Fisheries and the Canadian Industrial Development Branch supplied industrial-sized nylon gillnets to several Newfoundland fishermen on an experimental basis. The nets caught so many fish during this experimental period that the government subsidized their cost for all Newfoundland fishermen and heavily subsidized the replacement of nets that were increasingly being lost due to storms and trawler action as the 1960s became the 1970s. By 1965, the lost nets the provincial government subsidized fishermen to replace numbered 30,000—which was also the number of people in Newfoundland and Labrador that would lose their livelihoods 27 years later when the exhausted fishery closed.

From 1960 to 1962, the number of in-use nylon gillnets in Newfoundland jumped from zero to 6,737. By 1968 there were 42,837. As the industrial-sized plastic nets became more mainstream into the sixties, Newfoundland fishermen started sounding alarms to journalists and government officials about plastic gillnets harming the mother codfish that dwell in the depths and help communities of cod renew every year. Their concerns came from their own experiences as people who had to use the new nets because of their subsidized price and the related shift in market value from quality of cod to volume of cod. I found no record of any official effort made at the time to investigate fishermen’s concerns or incorporate them into policy. This is the world that Denis entered when he returned home to work on the sea.

In all the world’s oceans, industrial overfishing was set into motion with wartime technologies, such as plastics and radar, that were introduced into commercial fisheries in the 1960s. Those technologies have also enabled scientists to model estimates of how many fish are in the sea. If those models are accurate, then there may be half as many fish in the oceans today as there were in 1970.

The origin story of one mid-century fishing technology, industrial-sized nylon gillnets in Newfoundland, demonstrates crucial ways in which industrial overfishing is also a cultural artifact of industrial societies, revealing commercial desires, dominant scientific assumptions about reality, and global power relations. New nets were just one piece of a larger effort in Newfoundland and Labrador to transform rural fishing communities into efficient pseudo-factories, organized around a central fish processing plant with hourly shift work rather than family-based production in countless wharves and stages (traditional seaside buildings associated with the cod fishery). The industrial-sized nylon gillnets, designed by government agencies to indefinitely catch more (and more and more) codfish, mirrored the demands and desires of the expanding global markets that government officials hoped would transform rural areas from expensive sinks to profitable contributors.

They snagged in boat propellers, they snaked around crab pots and lobster buoys, they snared near the shore, always full of rotting fish.

As Newfoundland geographer Dean Bavington explains, the collapse of the Newfoundland cod reflects post-war managerial assumptions about the nature of fish and fishermen rather than the inevitable outcome of many resource users accessing a commons. Instead of protecting and promoting relationships between humans and fish, much of post-war fisheries management was geared toward determining the maximum number of fish that humans can take from the sea. This managerial attitude also links volume-based commodity production to urban settlers’ definitions of productivity and modernity—i.e. who does and does not have access to a livable future. The waste, the bycatch in this picture—of marine life and rural lifeways—powerfully illustrates a central claim of Max Liboiron and Josh Lepawsky’s new book, Discard Studies: that “social, political, and economic systems maintain power by discarding certain people, places, and things.”

The coast of rural Newfoundland is haunted by these attitudes and assumptions that render both fish and fishing communities disposable. They are tied into the very knots of the federally introduced four-hundred-foot plastic fishing nets designed to catch as many fish as possible without breaking down. They are drifting beyond harbor walls, circulating on the currents, capturing the fish that still survive, but they circulate within the harbor as well. These attitudes and assumptions make a net of their own, one in which Denis became ensnared when he came home to Newfoundland and named his fishing boat The Future. The people who introduced the ghost nets are gone, but the logics that moved them are still capturing myriad others, fishing the currents without them.

In contrast, the attitudes that many fishermen still living in Newfoundland outports bring to their fishing gear may provide a little light on this stormy coast. In Denis’s hometown, a handful of fishermen use smaller plastic gillnets inside the calm water of the harbor to catch baitfish for their lobster pots. Throughout this past winter, those fishermen mended their gillnets for more hours than I can count. They hung them in their stores and stages from hooks made from the crooked branches of alder trees and used homemade wooden shuttles to replace sections of plastic webbing that were torn or frayed. Come spring, when the risk of sea ice had passed, they set their nets in the harbor and buoyed them with floats they made from laundry detergent bottles painted blaze white. Last week I saw an otter sampling its fill of mackerel from such a net. Since I first interviewed him, Denis has moved into the city to be closer to medical services and his children who couldn’t find a way to make a living in their hometown. This town only has about 90 year-round residents now, down from the 300 or so that lived here before the collapse of the cod. By financial necessity every material that possibly can be is fixed and repurposed. Every tool lives many lives.

Author’s note: I use the term “fisherman” rather than the gender-neutral “fisher” because “fisherman” is the term that people I interviewed who hunt fish use to identify themselves. Some of those people use she/her pronouns. All the names in this piece are pseudonyms except the names of public figures. My deep gratitude to generous friends, colleagues, and mentors who read and commented on earlier drafts of this essay, to neighbors and collaborators on Newfoundland’s east coast, to helpful archivists at the Memorial University Maritime History Archives and The Rooms Museum, and to brilliant AN editor Natalie Konopinski.