Article begins

Disease is but the most obvious part of an epidemic. As coronavirus spreads, it fuels many other kinds of contagious forces.

AN editor’s note: How can anthropology help us to understand the current coronavirus? How do anthropologists respond to news coverage of and data about the spread of Covid-19? We invite anthropologists with expertise on infectious disease, anthropological approaches to epidemic and pandemic threats and “contagion,” zoonotic diseases, and government and health care infrastructure and responses, to add their comments and recommended reading.

No one touches anything on the Hong Kong metro these days. We do not hold the handrails. Instead, we jostle for locations along the wall where we practice a collective core exercise, balancing ourselves on nimble feet and engaged thighs. When an unmasked middle-aged man with a cough boards the train, bodies grow tense. This affect is transmitted between bodies (Brennan 2014), materializing as tense back muscles, uneasy glances, labored breathing beneath sticky masks. We turn our attention to our phones, noticing that emails once again end in appeals to “stay safe”—much as they did during protests last November—though now with the additional words “and healthy.” As we exit the station, a woman’s voice on the loudspeaker cautions us to wash our hands frequently and not to leave home if we have a fever. Some office buildings and restaurants now conduct temperature checks at the door—a cool body the prerequisite for entrance.

Image description: A photograph of a taxi with a sign in the window that reads “disinfected.”

Caption: Businesses innovate new ways to attract customers amid widespread anxieties that keep many residents self-quarantined at home. Hong Kong, February 2020. Ria Sinha

Practicing self-quarantine offers little relief from this anxiety, not least because reports claim the virus can spread through pipes between units in apartment complexes. Isolated at home, panic blossoms like a viral culture driven by contagious rumors, around-the-clock news coverage, and the compulsive draw of social media. Real-time maps of Hong Kong and the world help fuel this anxiety by plotting the location of each new confirmed case and listing details such as age, residence, and connections to other cases. We are plugged into smart phones and devices that tie us to this information network 24/7, and yet the combination of conflicting information and government distrust make it impossible to know just what to do. Hongkongers are making decisions based on their own analysis of the data—whether that’s translated into augmented personal protection, social distancing, or stockpiling of daily essentials. Rumors of impending shortages on social media spark shopping frenzies that cause everyday necessities to triple in price across the city. Toilet paper has become such a scarce commodity that armed robbers steal it at knife point.

In February, the World Health Organization released a Situation Report on the Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCov) which states that the “outbreak and response has been accompanied by a massive ‘infodemic’—an over-abundance of information—some accurate and some not—that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it.” The transmission of information itself has become another kind of outbreak, one that influences the spread of other contagious forces: for instance, scholars around the world have been tracking how (mis)information about Covid-19 is contributing to the spread of Sinophobia and Yellow Peril discourse.

The slogan #saveourselves now proliferates across a virus-stricken and politically-embattled city as residents work together to protect both their lives and their way of life.

The aura of objectivity surrounding numbers may make them appear as a panacea for such uncertainty, panic, and prejudice. As the apparent bearers of unmediated truth, numbers can be seductive in their promise of providing concrete answers (Merry 2016; Porter 1996). Indeed, the Covid-19 outbreak has been characterized by the proliferation of enumerated data: we chronicle numbers with the meticulousness of an accountant’s ledger, fixated on mortality rates, epidemiological predictions, and real-time updates on the number of suspected, confirmed, and quarantined cases. These figures are keenly followed in the local Hong Kong media, where the number of new cases is scrutinized and interpreted to presage the course of the outbreak, acting as a barometer of the threat to public health. Much as anthropologist Sarah Luna (2018) has written about contagious rumors, such infectious numbers are circulated between loved ones as a form of care while simultaneously intensifying collective panic.

Yet the question of what numbers are enumerating is far from straightforward. Such evidence does not stand outside of the context of the health intervention it also enacts. Consider February 13, 2020, for instance: the day the world awoke to nearly 15,000 new Covid-19 cases after clinical diagnosis began to be counted in China. Only five days earlier, cases which had been confirmed were abruptly discounted when the Chinese government decided that asymptomatic individuals who tested positive would no longer be enumerated in official figures. A shortage of testing kits, hospitals overwhelmed with suspected cases and too few staff, and virus-positive but asymptomatic or mild cases that go untested and uncounted mean that reliable infection and mortality rates might never be determined.

In today’s Hong Kong, this pervasive sense of anxious uncertainty is also laced with rage.

Image description: A photograph of an outdoor basketball court filled with people holding up open umbrellas of many colors. At the front of the crowd, a man speaks into a microphone through a face mask.

Caption: Protests against the establishment of quarantine centers have become an almost daily occurrence in the city as trust in the government is at an all-time low, Fo Tan, Hong Kong, February 2020. Justin Haruyama

On a cold, rainy evening in February 2020, hundreds of people gathered on an outdoor basketball court to protest the transformation of the nearby Chun Yeung public housing estate into a quarantine center. Each of us wore a mask, defying the government’s October 2019 ban on wearing face masks at public gatherings. Young men unfurled a black banner carrying the rallying cry of the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement: “Liberate Hong Kong. Revolution of our Times.” Protest medics kitted out with large gas masks, utility vests, and belt bags of first-aid supplies stood ready to assist protesters should the riot police, who were lurking just outside the court, decide to attack. As the mood of this crowd attested, rage has become an ordinary affect (Stewart 2007) in today’s Hong Kong. Such complexities are often distilled and fixed into a familiar narrative of outbreak—spread—containment.

Contrary to media reports in both the Hong Kong and international press, the people gathered here did not express fear of infection from the quarantine center. Rather, they were outraged at yet another betrayal perpetrated by the Hong Kong government: with no assistance and precious little information, they have been denied access to the public housing flats where they planned to move next month. Many of them had already terminated their current leases. As one elderly man asked rhetorically, how will they cover rent elsewhere with the meager $6,000 HKD (approximately $770 USD) compensation they have received for the government’s breach of their already-signed new contracts? More than a few may soon find themselves with nowhere to live.

In the packed quarters of such protests, it is impossible to maintain the one to two meters of social distance advised by Hong Kong health authorities. Yet, hundreds have gathered here anyway—a testament to other embodied intensities proliferating across Hong Kong these days. As sociologist Ching Kwan Lee has illustrated, the pro-democracy movement has aroused a form of collective effervescence among people striving to construct a new sense of Hong Kong identity and community solidarity. Like the virus, this effervescence spreads through existing networks of interpersonal relations. It materializes affectively as a “presencing of the people,” a defining feature of populism (Mazzarella 2019: 49).

Fueled by the near-total loss of trust in the government to protect the interests of ordinary Hongkongers, the slogan #saveourselves now proliferates across a virus-stricken and politically-embattled city as residents work together to protect both their lives and their way of life.

Image description: A photograph of a long line of people queuing in front of a table from which people are dispensing face masks and hand sanitizer. An orange concrete sculpture depicting twisted bodies stands in the background.

Caption: Demonstrating the ethos of #saveourselves, the pro-democracy protest network StandUpHKers distributed face masks and hand sanitizer to students and staff short on supplies, with the Pillar of Shame statue memorializing the Tiananmen Square Massacre in the background. University of Hong Kong, February 2020. Justin Haruyama

Compounding this sense of distrust in the government are traumatic memories of an earlier epidemic in 2003: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Numerous reports (e.g. Benitez 2003; Goldizen 2016; Mason 2016) have since argued that the lack of transparency surrounding the SARS outbreak—including a cover-up of early cases by health officials in Guangdong—were catastrophic mistakes, which few believed the authorities could make again. Yet the Covid-19 epidemic is proving that it is even more difficult to trust the data coming from Chinese health authorities now that the continual revising of diagnostic criteria has furnished an incomplete and untrustworthy picture of the scale of the outbreak in China, with ramifications for international preparedness and response. As Hong Kong shares a physical and political border with mainland China, it has been precariously dependent on China’s “number narratives” (Brooks 2017) to mount a local response to the epidemic—case numbers are critical in timing government decisions to screen arrivals and restrict cross-border travel. Inevitably, imported cases have now progressed to local transmission and as the number of infections increase so does public distrust of the government’s handling of the outbreak.

Nowhere is this distrust more poignantly portrayed than in the social media diaries of Wuhan residents. In a genre dubbed “diaries in a lockdown city,” stories of fear, helplessness, and abandonment are going viral in China—at least, that is, if they manage to escape state censorship. Isolation and confinement further amplify uncertainty over what to do and what to believe.

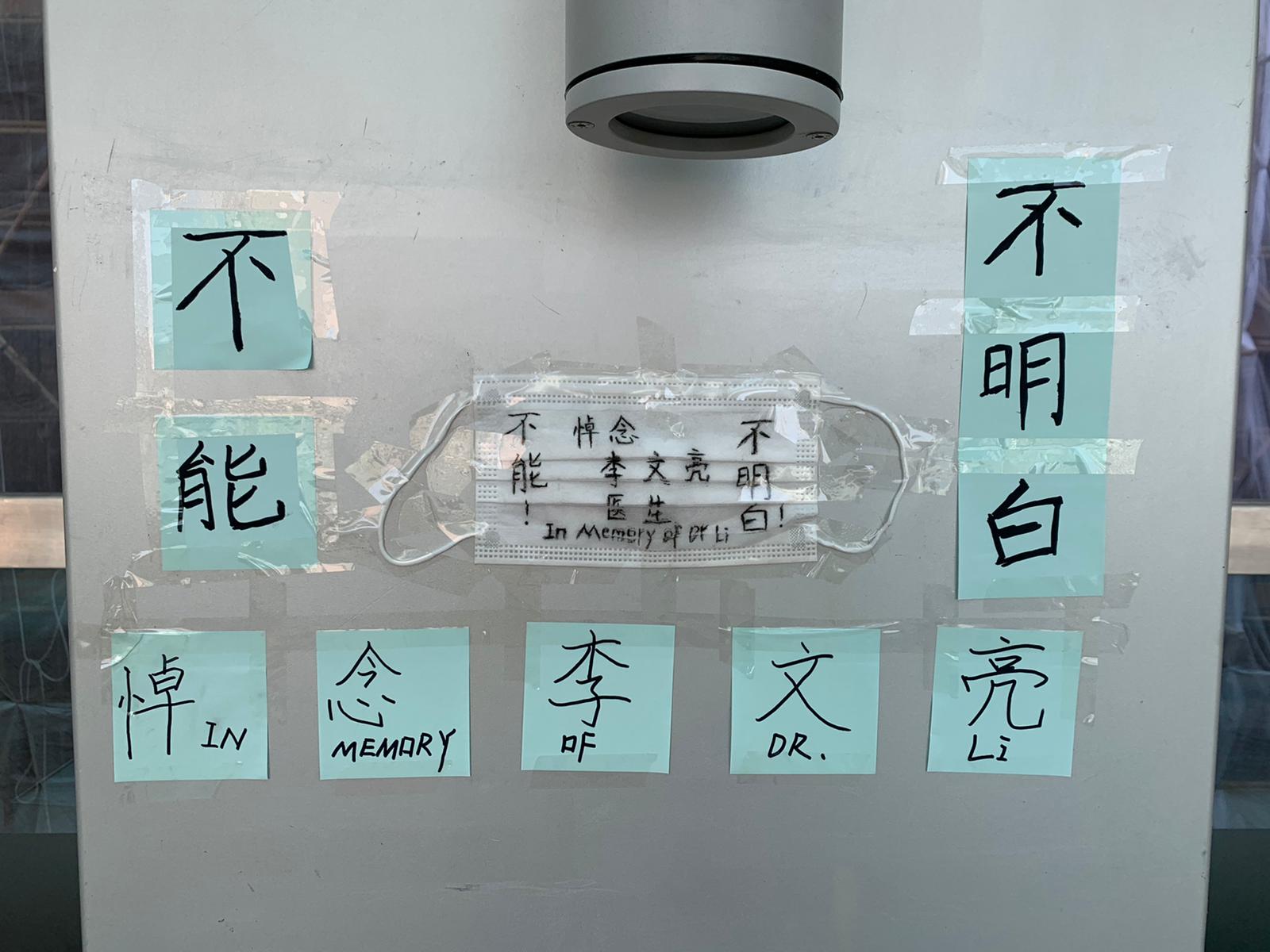

Image description: A photograph of post-it notes and a face mask taped to a wall with Chinese and English text written on them. The English text is “In memory of Dr. Li.”

Caption: This memorial was taped to a wall on the University of Hong Kong campus. The Chinese characters on the left and right read “not able!” and “do not understand!”, referring to the forced confession Doctor Li Wenliang was compelled to make, in which he acknowledged he was “able” to cease whistle-blowing and that he “understood” he would be severely punished for failing to do so. Doctor Li was one of the first to raise the alarm about Covid-19 in Wuhan in December 2019, before dying from the disease himself on February 7, 2020. A few days after this photograph was taken, someone removed the face mask, but not the post-it notes bearing the same message. Hong Kong, February 2020. Ria Sinha

Tracing the spread of the Covid-19 virus requires following many kinds of transmissions and contagions, from infectious numbers to populist mobilizations, viral rumors to affective atmospheres. These forces course along multiple material-semiotic networks at different speeds and intensities, unsettling and transforming the city as they circulate. And yet, as literary scholar Priscilla Wald (2008) has shown, such complexities are often distilled and fixed into a familiar narrative of outbreak–spread–containment. Ethnographic, interdisciplinary, and publicly-engaged scholarship all have a crucial role to play in complicating such reductive narratives and bringing other stories to light. As the everyday experiences of Hongkongers reveals, the form and significance of this epidemic is still anything but settled. The virulent transmissions of Covid-19 may yet remake this city—and the world—in profound and unforeseeable ways.

Justin Haruyama is a PhD candidate in cultural anthropology at the University of California, Davis. He resides in Hong Kong, where he is completing his dissertation on diverse modes of relationality between Chinese migrants and Zambians—from violence at Chinese-operated coal mining sites to proselytization by Jehovah’s Witnesses in Lusaka.

Laura Meek is a medical anthropologist and assistant professor in the Centre for the Humanities and Medicine, University of Hong Kong. Her work engages knotty global health challenges through the lens of feminist and postcolonial science studies. Her current book project is Pharmaceuticals in Divergence: Radical Uncertainty and World-Making Tastes.

Ria Sinha trained as an infectious disease scientist at Imperial College London and is currently senior research fellow in the Centre for the Humanities and Medicine, University of Hong Kong. Her interdisciplinary research considers the complex and dynamic sociocultural, ecological, technological, and scientific determinants of infectious disease emergence and management.

Please send your comments and ideas for SMA section news columns to contributing editors Dori Beeler ([email protected]) and Laura Meek ([email protected]).

Cite as: Haruyama, Justin, Laura Meek, and Ria Sinha. 2020. “Going Viral in Hong Kong.” Anthropology News website, March 3, 2020. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1364