Article begins

Countering Trump begins by recognizing his role as troller-in-chief.

The United States and the world have now spent two years trying to figure out how to deal with an anti-social president. The task holds even more importance over the next two years as Democrats and Never Trump Republicans consider how to challenge an incumbent president in 2020. Formulating an effective strategy should start by recognizing the ways Trumpian discourse adheres to prototypical “trolling” behavior and responding accordingly.

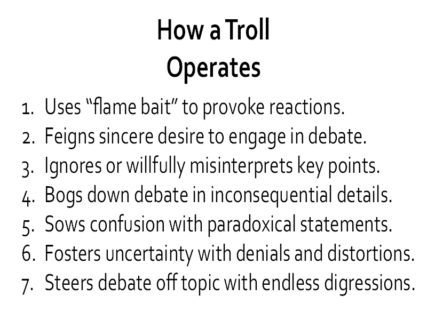

The concept of trolling, first studied by Judith Donath (1999) and further analyzed by Susan Herring and colleagues (2002), refers to actions by someone who baits and provokes others in online forums, “often with the result of drawing them into fruitless argument and diverting attention” away from the topics under discussion. Similar to and often overlapping with flaming (actions “intended to insult, provoke or rebuke”), the typical troll thrives on attention, especially negative attention that he (the troll is often a male) receives by sowing discord and instigating emotionally reactive responses. A troll is a provocateur who excels at disruption and digression particularly when those engaging with him fail to recognize his behavior as trolling.

Trump trolls the media and citizens with tweets and statements that sow confusion and provoke futile arguments. He often achieves this by making paradoxical statements. Take, for example, his prevarication about the evidence pointing to the role played by Mohammad bin Salman (MBS), the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia, in the premeditated murder of Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi.

Perhaps the most important way to deal with this particular troll is to simply recognize and label his behavior as “trolling.”

“We may never know all of the facts surrounding the murder of Mr. Jamal Khashoggi,” Trump counseled in an official statement released by the White House (and what may be the first propaganda piece issued by an American president on behest of a foreign authoritarian regime). Trump conceded that “it could very well be that the Crown Prince had knowledge of this tragic event,” but then again, he opined, “maybe he did and maybe he didn’t!”

Later, in a Fox News interview, Trump asked rhetorically, “Who could really know?” Then, in an interview with the Washington Post, Trump reiterated: “Maybe he did and maybe he didn’t. But he [MBS] denies it. And people around him deny it. And the CIA did not say affirmatively he did it, either, by the way. I’m not saying that they’re saying he didn’t do it, but they didn’t say it affirmatively.”

Trump “seeks to confuse and deceive, rather than to be clear,” just as the troll in Susan Herring’s (2002) analysis does. Senators later briefed by the CIA had no trouble recognizing “that this was orchestrated and organized by people under the command of MBS.”

Trump made similar discursive moves in his response to the Fourth National Climate Assessment (NCA4) released by the federal government—an evidence-based report that warns of the need to take immediate action to counter the economic and health impacts of climate change. In what the Washington Post described as “a freewheeling 20-minute Oval Office interview,” Trump went off on a tangent that touched on trash in the oceans, dirty air in Asia, and myriad topics unrelated to the central issue of climate change or the key conclusions of NCA4.

Trump’s critics often characterize such stream-of-consciousness ramblings as nonsensical gibberish, but such moves are central to the troll’s strategy. Delving into inconsequential minutiae that are barely tangential to the topic at hand allows the troll to feign sincerity at addressing the topic while he shifts the conversation toward futile arguments. Trump either misinterprets—or ignores altogether—key conclusions from evidence-based reports to shift the conversation; or he engages in strategies of denial and distortion to sow doubt on claims. In response to the conclusions of NCA4, Trump rejoined, “I don’t believe it” (denial). “You look at our air and our water, and it’s right now at a record clean,” Trump told the Washington Post (distortion).

Seven signs you’re dealing with a troll. Adam Hodges

Interactants expect a certain level of mutual cooperation from conversational partners (Grice 1975). But when trolls make discursive moves that obfuscate, confuse, deny and distort, those engaging with the troll are often at a loss on how to respond because the troll’s conversational contributions are so far removed from the norms. When asked by the Washington Post to reply to Trump’s comments on NCA4, Andrew Dessler, a professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University, simply remarked, “How can one possibly respond to this?”

Trolls take pleasure in disrupting the social order and getting a rise out of others. When others do engage with the troll, it is easy to fall into a reactive response that either follows the troll down the rabbit hole of a futile or off-topic argument, or mimics the troll’s inflammatory style by striking back in kind. Trolls often use “flame bait” (statements designed to inflame and infuriate) to provoke others into insult-driven tit-for-tats. Even Dessler couldn’t help but labeling Trump’s comments on NCA4 “idiotic.”

So, how do we deal with a president who governs by trolling?

Completely ignoring the president altogether clearly isn’t an option: a viable democracy requires engagement to affect democratic accountability. And the pervasiveness of his trolling behavior makes it impossible to simply ignore or shun. His trolling goes well-beyond the 547 people, places, and things Trump has insulted on Twitter; it seeps into every aspect of his governance, as illustrated here. Returning Trump’s provocations in kind merely feeds his ego and fails to deal with the implications of his policy decisions. I agree with Michelle Obama on the need to go high “when they go low.” However, trying to respond with rational counter-arguments to Trump’s every claim or distortion ignores the realization that trolls act as they do to deliberately steer the conversation off topic into endless inconsequential digressions. Genuine debate is not their goal. Trolls are bad-faith conversational partners where even heated political debate requires a basic level of Gricean cooperation.

Perhaps the most important way to deal with this particular troll is to simply recognize and label his behavior as “trolling.” Armed with the awareness of how a troll operates, we can respond by not falling for the distractions, not getting stuck in a state of constant outrage, and consistently working to keep the discourse focused on the key issues at hand.

Adam Hodges is a linguistic anthropologist with interests in political discourse. His books include The ‘War on Terror’ Narrative: Discourse and Intertextuality in the Construction and Contestation of Sociopolitical Reality, and his articles have appeared in Discourse & Society, Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, Language & Communication, and Language in Society.

Cite as: Hodges, Adam. 2018. “Government Of, By, and For the Trolls.” Anthropology News website, December 20, 2018. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1241