Article begins

“Have you seen Roma?” This is perhaps the single most prevalent question I get as a response every time I talk about the subject of my research. Roma is not the first film to address the realities of paid household work in Latin America in complex nuanced and poignant ways, but it is the first film to reach a global audience and the first to garner widespread critical acclaim.

Household work as an institution of urban Latin American life often goes unnoticed or ignored. Roma, however, sparks conversations and attracts media attention, because it puts the subject of household workers into the center of public debate. Set in Mexico City in the early 1970s, the film tells the story of Cleo and her life as a household worker for an upper-middle class family in Mexico City’s Roma neighborhood.

The film is based on the life of director Alfonso Cuarón and his nanny, Libo, who Cuarón considers a member of his family to this day, having played an important role in his upbringing, and to whom the film is dedicated. The autobiographical lens reveals the director’s ethnographic sensibility. We viewers are invited to observe Cleo’s daily life. Her routines are on display, including difficult personal life events—unexpected pregnancy, romantic love gone awry, a stillbirth, a New Year celebration, and a trip to the seaside where two of the children in her care nearly die. And amidst these all, we get a sharp view of the gender, class, ethnic, and racial dynamics at play between Cleo and the family she works for, most brutally and honestly shown in the relationship between Cleo and her employer, Señora Sofia. Their relationship oscillates between the intimate and the distant, between the loving and the violent, thus showing the structural inequalities that organize Cleo’s life as a household worker.

Household workers’ rights struggles

Roma’s release could not be more timely. Although the setting of the film is almost 50 years ago, the challenging issues it addresses—discrimination, precarity, structural violence, to name but a few—are as relevant in 2019 as they were back in the 1970s. For those of us who do research on paid household work in Latin America, Roma serves as a vehicle to shed light on and discuss the breath of research happening on this subject. Long gone are the days in which the ground-breaking Muchachas No More was one of the few books on the subject and research on household work was a novelty.

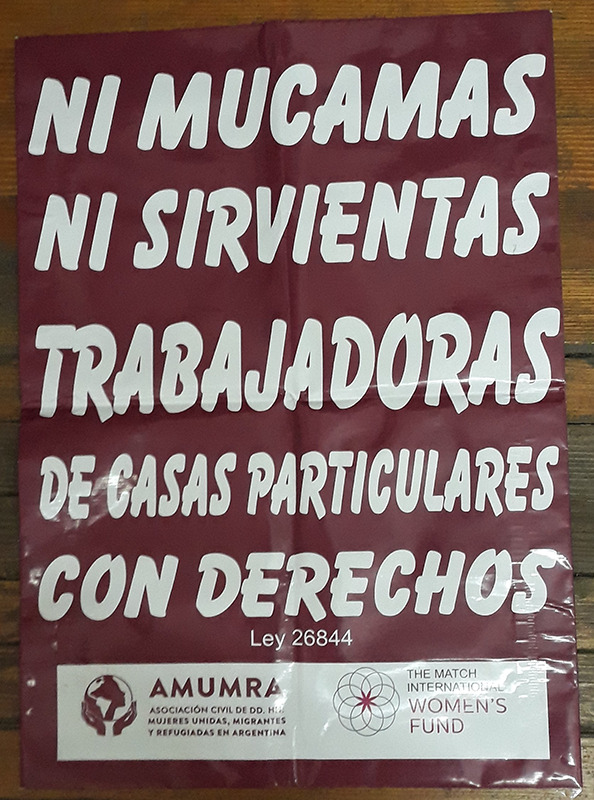

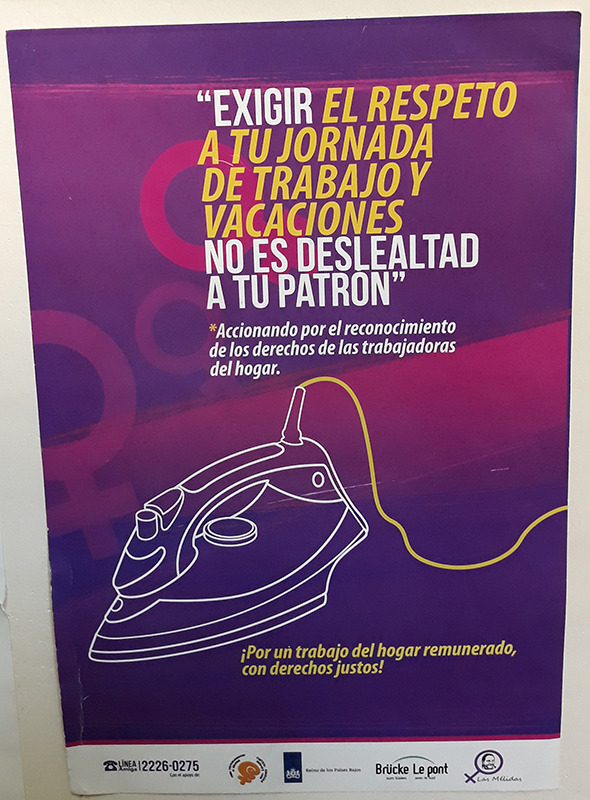

Roma comes out at a time when household workers’ struggle for equal rights is gaining increasing visibility. Cuarón ends the film credits with an invitation to viewers to support household workers’ rights organizations in the United States and Mexico, and in July of this year a National Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights was introduced by Senator Kamala Harris and Representative Pramila Jayapal to the United States Congress. For anthropologists, the issue of labor rights is perhaps the most important one that Roma addresses and the one that ethnographers are well-equipped to examine, try to understand, and to contribute solutions.

Household work research and activism

Ethnographic fieldwork can shed light on the challenges inherent in regulating a job that takes place behind closed doors. The difficulties in determining what counts and what doesn’t count as household work play out between household workers and employers with respect to the law in the everyday contexts of intersectional and structural inequalities. As a research collaborator summed up for me the complexity of social relationships in paid household work, “these are not labor lawsuits, they are divorces of work.” Her perspective, as a lawyer who works for the Work Tribunal for the Personnel of Private Households in Buenos Aires (an administrative court where household worker lawsuits are resolved), illustrates the distinctiveness of these disputes between household workers and former employers.

The last three decades have seen an explosion of interest in household labor by humanities and social science scholars. Anthropologists can play key roles in this research beyond study groups, symposia, and academic conference panels by adding their distinctive on-the-ground research perspectives to the struggles of these workers and the organizations that advocate on their behalf. For instance, the transnational interdisciplinary Network of Research on Household Work in Latin America (Red de Investigación sobre Trabajo del Hogar en América Latina-RITHAL) serves to facilitate interdisciplinary dialogue and conversations.

RITHAL’s core objectives promote research collaborations, increase the visibility of research on household work, and open up venues for academic discussion and exchange, as well as raise awareness of household workers’ struggles and support social change to improve household workers’ lives in Latin America. These objectives are reflected in RITHAL member anthropologist Jurema Brites‘ and her graduate students’ collaboration with the non-governmental organization Themis and leaders of Brazilian household worker unions at the recent 2019 Anthropology Meeting of Mercosur—RAM. The Network’s commitment to partnerships between research, activists, and workers will include a website with information on household workers’ rights, best practices across Latin America, and links to household workers’ organizations. A web-based platform will connect RITHAL members to household workers’ collective struggles. This is significant because it shows how academics and activists can collaborate to generate research that is useful to household workers’ struggles for labor rights and social justice.

The upcoming 2019 AAA/CASCA Annual Meeting in Vancouver will include the panel “Adding Color to “Roma”: Household Employees’ Lives and Daily Realities in Cities of the Global South” and a RITHAL meeting. Those interested in attending should contact the author at [email protected]. Those interested in joining RITHAL’s mailing list should contact its founder and coordinator Erynn Masi de Casanova at [email protected].

Walter E. Little ([email protected]) is contributing editor for the Society for Economic Anthropology’s section news column.