Article begins

It was a special treat to visit my great-aunts and their magical house in the Philippines. The house was intricately carved and painted a riot of pastel colors earning its name, “The Cake House.” A balay ukit (“carved house”), the Cake House is an architectural structure indigenous to the twentieth-century Philippines. Many balay ukit are “ancestral houses” passed down within a family and, in cases such as the Cake House, are recognized as icons of national heritage. Contrary to the dark and gloomy haunted house, balay ukit were designed for the interplay of sun, wind, and color. Native builders were aware that raw materials, especially trees, had been the dwellings of nature spirits or what people called taglugar. Tropical architects had various strategies to acknowledge that cutting a tree was destroying taglugar homes and in turn the natural world.

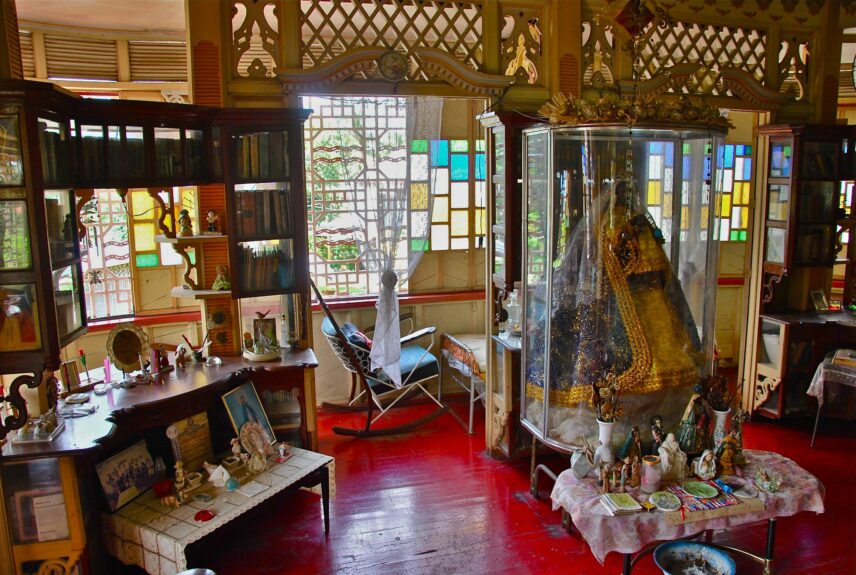

Inside the Cake House is no less enchanted. Encased in a glass box at the heart of the house resides a life-size image of Santa Regla, a Black Madonna and patron saint of a faith healer whose cult following was centered in the Cake House with my aunts as the main sponsors. I grew up on stories about Santa Regla, and even met the medium and her entire family one summer as a child. Years later, I arrived to the house as an anthropologist. As I stepped off the public transport and approached the gate, passengers craned their heads out the windows. One person said, “Dios ko! That place is haunted.” Already, whispers of ghosts trailed me into the house. With the tropical sun, rain, and ghost-talk buzzing around my arrival, I had to figure out how to approach the storytelling of specters.

One of the guides I turned to is the acclaimed writer, Shirley Jackson. Her novel, The Haunting of Hill House (1959) depicts one of the now archetypal “haunted houses” of the twentieth century imaginary. Jackson lived most of her adult life between New York and Vermont. However, the infamous Hill House was based on pictures of the ostentatious California mansions built by Jackson’s ancestors, the Bugbee clan, during the height of the Depression. I was surprised to find that the model for Hill House was not from the seasonally dark climes of the American Northeast, but rather what Jackson called “big old California gingerbread houses.” I could not ignore the parallels between a haunted gingerbread and cake house in warm climates.

The most obvious parallel between the novel and my own haunted house story was that Jackson made one of the main characters an anthropologist, Dr. John Montague. In the story, he obtained this degree hoping it would grant him some scholarly respectability with respect to his “unscientific” interest in supernatural phenomena. Montague’s character was shaped within a positivist paradigm that defined any phenomena not legible to science would either be explained at some point or just persisted as a superstitious relic. If there were ghosts in the Cake house, I figured they are my kin, so I understood my work to be what Donna Haraway called “response-ability, not in the abstract but in homely storied cultivated practice.” Following scholars on postcolonial to settler-colonial studies, hauntology, debating the ontological turn, and multispecies ethnography, I attuned myself to more than empirical data, and allowed the writing to follow suit.

Most people found it humorous or were dismissive as I went about asking about ghosts and spirits. There were a few who told me the Cake House was cursed and soon I would be too. As a descendant who bears the name of the house, these ghosts are my kin. But as a diasporic subject raised in the United States, I had few tools to relate to my ancestors.

I worked out some of the whispers into oral histories. There were rumors that the current healer of Santa Regla was a sorcerer that had bewitched my last living aunt. Hiligaynon-speaking locals regarded the house as mari-it. In the pioneering work of the anthropologist Alicia Magos, mari-it was usually heard in Visayan maritime contexts to describe perilous waters. On land it was a “danger zone” largely associated to native trees, especially balete or acacias, where taglugar abide. Any inhabitant of Panay Island will have heard or been told to say “tabi-tabi, po” (let me pass, sir) to pay respect and try not to disturb the spirits who dwell in certain places. When misfortune or illness befalls someone, there are many who still consult faith healers like Santa Regla. I have heard diagnoses range from usog (evil eye), attack by an engkanto (nature being), or tuyaw (message from the dead). One day when I became ill, a friend insisted that I consult with a healer who pronounced I should immediately vacate the Cake House. It was too mari-it.

In 2007, an international airport was built near the Cake House. It did not take long for the arrival of the airport in this region to create a broader context for mari-it. As the town became a regional transportation hub, it brought in road widening projects. Long untouched groves of trees that had been regarded as mari-it were being cut down and entombed in concrete. Mari-it became stories of accident-prone areas, populated with ghosts, apparitions of a white lady, and the specter of death. Then in 2013, typhoon Haiyan, one of the most powerful recorded cyclones in history, made landfall in the central Philippines. Entire villages were wiped out. In the age of climate change, mari-it in the tropical archipelago seems to be everywhere. Indigenous groups of the area such as the Atis and Panay Bukidnon, have long warned that illness, misfortune, and mass destruction is brought on by angry taglugar.

What I thought was going to be an ethnography that resonated with haunted house or ghost stories turned out to be a lot more. By taking up residence in the Cake House, I grew attuned to a plurality of liveliness—living and dead, visible and invisible. The healer of Santa Regla was said to channel spirits that spoke English, Mandarin, and Tagalog, though the medium herself did not speak those languages. Was it the dead or the taglugar speaking to me? While Shirley Jackson’s work detailed the banal evils of the newly established upper middle classes of America, she never quite confronted that the “gingerbread houses” of her forebears encrypted legacies of settler colonial and ecological violence. For me, the Cake House is not just haunted, it is mari-it, which for my story means translating a troubled relationship between structures that humans of a tropical archipelago made in the wake of Spanish and US colonization and how attuning to this relates to spirit beings that dwell in the same landscape. Do we have an incantation or a tabi currently powerful enough to address these very troubled taglugar? Can an ethnography attuned to the more than human worlds constitute a way for me to connect with my ancestors?