Article begins

A Pandemic Auto Ethno Graphic

Credit:

Sonja Nosisa Noonan-Ngwane

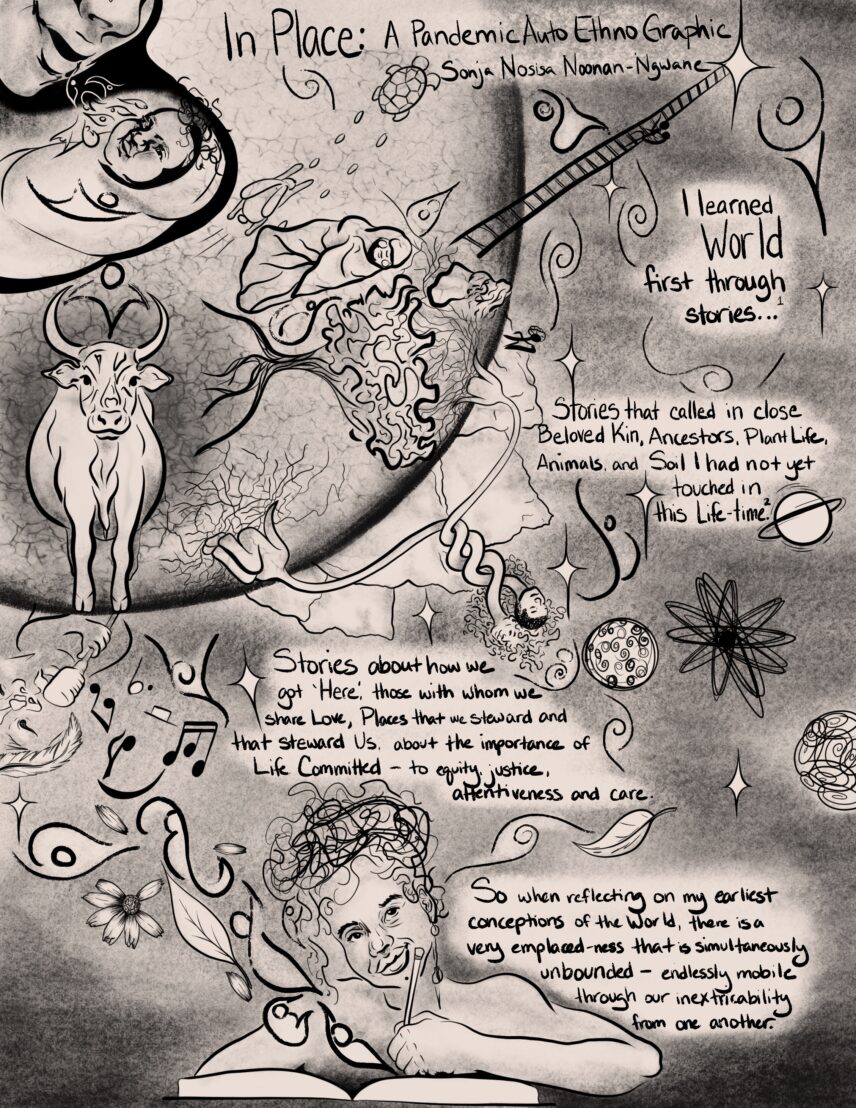

Image description: At the bottom of the page the author holds a pencil over a book wearing a thoughtful face and curly hair piled on their head. Out of the pencil starts a stream of Ancestor Spirits, flowers, leaves, stars and music notes that flow into the top portion of the page populating a globe and outer space with illustrated Stories including the following:

- Nina’s Voice (Nina Simone singing into an old-style microphone),

- Xhosa Cattle (cow facing forward with big horns emerged from a wet spot in the Earth with an Ancestor between its horns),

- Dreaming Together (two people on the globe are seated far apart—their necks are extremely elongated and twist together ending in their skulls gently touching, facing away from one another—one has voluminous curly hair and the other has a fade, both are softly smiling),

- Ancestors Don’t Get on Government Trucks (a small stick figure is shown climbing up a mountain with a walking stick, depicting my Ancestor’s refusal to follow apartheid demand to abandon Our Ancestral Graves and Home up the mountain),

- the Tree of Life (a big tree with winding roots and branches),

- Initiate (someone wrapped in a blanket from head to toe with a soft neutral face, hidden eyes and full accentuated cheeks, walks alongside the Tree of Life),

- the Tortoise and the Hare (a hare pursues from behind a tortoise who is walking steadily beneath the title of the work, “In Place: A Pandemic AutoEthnoGraphic” by Sonja Nosisa Noonan-Ngwane),

- the Big Bang (off of the globe’s surface is depicted Space with many Stars, Ancestors, atomic expansion, and three planets—one rocky, one gaseous, one windy),

- and Invocation (in the upper left-hand of the page is an image of an adult facing an infant—there are Ancestor Spirits coming from the adult’s mouth as they tell Stories to the swaddled infant—these Spirits are holding, looking at and dancing around the child).

Credit:

Sonja Nosisa Noonan-Ngwane

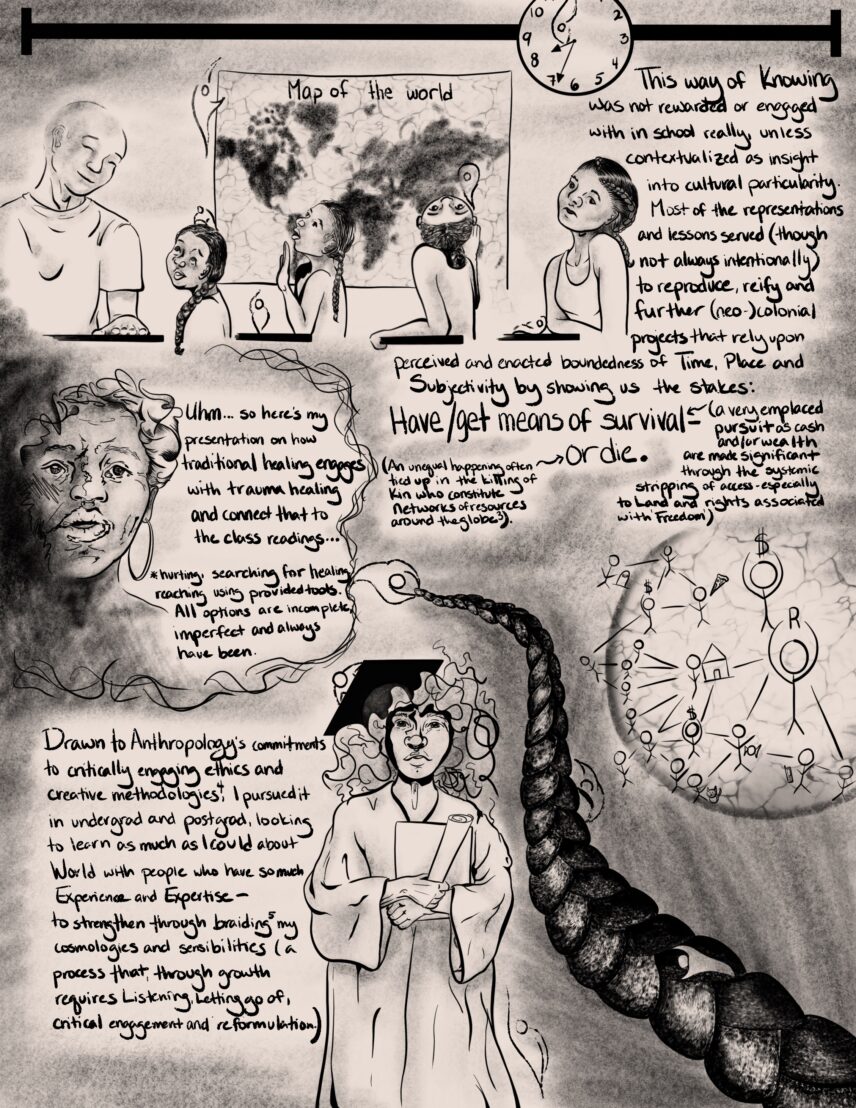

Image description: A vaguely defined teacher stands with their hand on the desk of the child-version of the author who is looking skeptical. Behind them are three increasingly older versions of the author all seated in classroom desks. Second from the left is raising her hand and has her mouth open. Third is holding onto his desk, looking at a map of the world on the wall and raising a hand. The last is sighing and looking at the reader.

Below that, the undergrad-age author is shown in shadow looking out with mouth open to give a presentation. Their face reads anxious, dissociated and vigilant. This aside is defined by darker shading and a squiggly many-lined border. The text of this aside reads: “Uhm… so here is my presentation on how traditional healing engages with trauma healing and connect it to the class readings… hurting, searching for healing, reaching using the provided tools. All options are incomplete, imperfect, and always have been.” Beside the illustration of the undergrad-age author is an outline of the world with stick figure people on it holding above their heads symbols of the means of survival and what they translate into (money, housing, food, medication, phones, end-of-life care, and so on) to depict transnational flows of resources. At the bottom of the illustration, the author stands wearing a graduation gown and cap and holds a diploma and certificates. There are Ancestors hiding in the gown, sitting on the cap, tugging at the author. Creating a border between the author and the globe is a big braid with Ancestors dancing along it. There are Ancestors distributed across the page—they dance on the braid, the author’s body, desks, the classroom map and more.

The text woven throughout this image reads: “This way of knowing the world was not rewarded or engaged with in school really, unless contextualized as insight into a cultural particularity. Most of the representations and lessons served (though not always intended) to reify, reproduce and further (neo-)colonial projects that rely upon perceived and enacted boundedness of Time, Place and Subjectivity by showing us the stakes: Have / get the means of survival (a very emplaced pursuit as cash and/or wealth are significant through the systematic stripping of access especially to land and associated rights of ‘freedom’), or die (an unequal happening often tied up in the killing of Beloved Kin who form networks of resources around the globe). Drawn to anthropology’s commitments to ethics and creative methodologies, I pursued this in undergrad and postgrad, looking to learn as much as I could about the world from people who have so much Experience and Expertise, to strengthen through braiding my cosmologies and sensibilities (a process that, through growth requires listening, letting go of, critical engagement and reformulation).”

Below that, the undergrad-age author is shown in shadow looking out with mouth open to give a presentation. Their face reads anxious, dissociated and vigilant. This aside is defined by darker shading and a squiggly many-lined border. The text of this aside reads: “Uhm… so here is my presentation on how traditional healing engages with trauma healing and connect it to the class readings… hurting, searching for healing, reaching using the provided tools. All options are incomplete, imperfect, and always have been.” Beside the illustration of the undergrad-age author is an outline of the world with stick figure people on it holding above their heads symbols of the means of survival and what they translate into (money, housing, food, medication, phones, end-of-life care, and so on) to depict transnational flows of resources. At the bottom of the illustration, the author stands wearing a graduation gown and cap and holds a diploma and certificates. There are Ancestors hiding in the gown, sitting on the cap, tugging at the author. Creating a border between the author and the globe is a big braid with Ancestors dancing along it. There are Ancestors distributed across the page—they dance on the braid, the author’s body, desks, the classroom map and more.

The text woven throughout this image reads: “This way of knowing the world was not rewarded or engaged with in school really, unless contextualized as insight into a cultural particularity. Most of the representations and lessons served (though not always intended) to reify, reproduce and further (neo-)colonial projects that rely upon perceived and enacted boundedness of Time, Place and Subjectivity by showing us the stakes: Have / get the means of survival (a very emplaced pursuit as cash and/or wealth are significant through the systematic stripping of access especially to land and associated rights of ‘freedom’), or die (an unequal happening often tied up in the killing of Beloved Kin who form networks of resources around the globe). Drawn to anthropology’s commitments to ethics and creative methodologies, I pursued this in undergrad and postgrad, looking to learn as much as I could about the world from people who have so much Experience and Expertise, to strengthen through braiding my cosmologies and sensibilities (a process that, through growth requires listening, letting go of, critical engagement and reformulation).”

Credit:

Sonja Nosisa Noonan-Ngwane

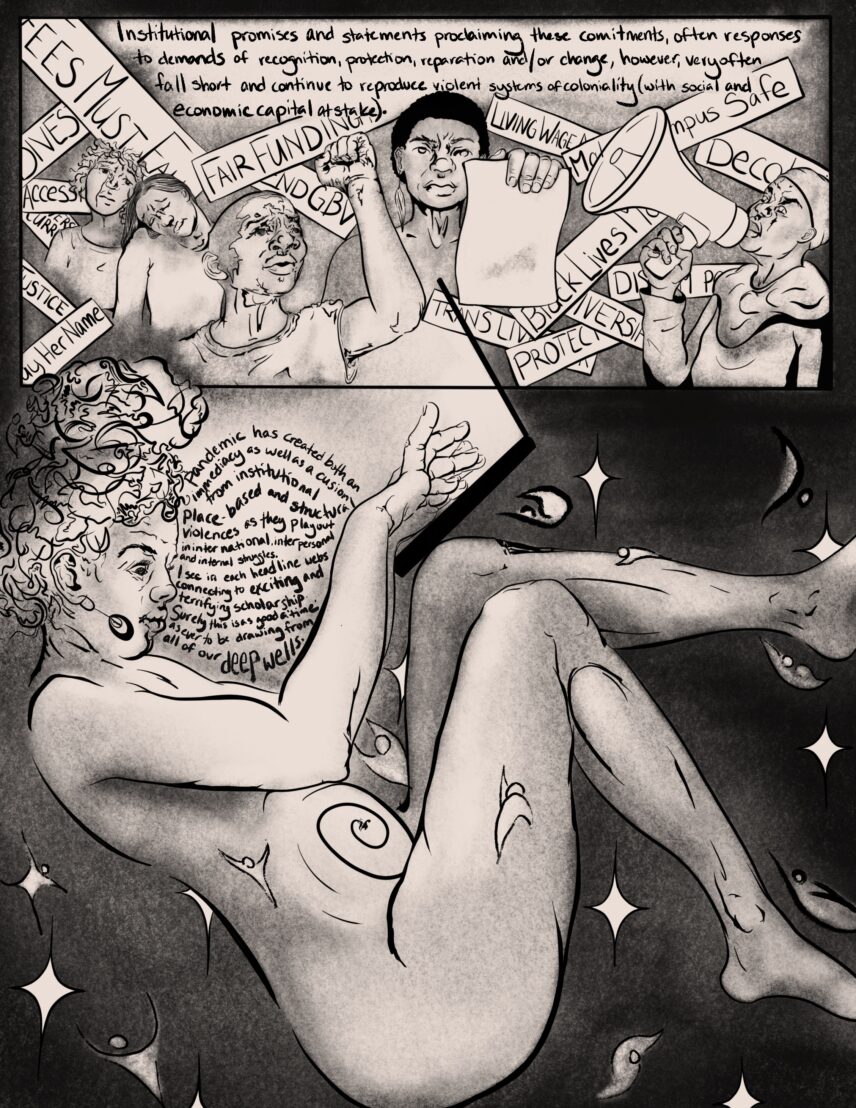

Image description: Five people are shown in expressions of protest. From right to left, two people are holding one another as they grieve, closer in the foreground a person with very short hair is holding up their fist and parting their mouth to speak looking impassioned, centered is someone sternly holding up to face the reader a piece of paper, and the person on the far right is holding a megaphone. They are all surrounded by signs elaborating institutionalized injustice inclusive of the following discernable words: Fair Funding, Divest, Accessibility, Diversify Curricula, Justice, Say Her Name, Fees Must Fall, End GBV, Living Wage, Trans Lives Matter, Black Lives Matter, Protect, Diversity, Decolonize, Make Campus Safe, Disarm. Many of these signs are partially obscured.

The author types on and is illuminated by a laptop balanced on their knee. Their body is floating in a semi-opened fetal position surrounded by Ancestor Spirits and Stars. The background is dark like layered compressed charcoal, set off by the laptop’s brightness that splashes across the author, as well as the soft glow of the Ancestors and Stars. The author’s eyes are fixed on their belly button which sits in the center of a spiral that spans across their stomach. They are wearing long earrings with a Cowrie shell that dangle close to their mouth. Their hair is piled in a bun spilling over with curls and frizz.

The text on this image reads: “Institutional promises or letters proclaiming these commitments, often responses to demands of recognition, protection, reparation and/or change, very often fall short and continue to reproduce systems of coloniality (with social and economic capital at stake). Pandemic has created an immediacy as well as a cushion institutional place-based and structural violence as they play out in international, interpersonal, and internal struggles. I see in each headline webs connecting to exciting and terrifying scholarship. Surely this is as good a time as ever to be drawing from all of our deep wells.”

The author types on and is illuminated by a laptop balanced on their knee. Their body is floating in a semi-opened fetal position surrounded by Ancestor Spirits and Stars. The background is dark like layered compressed charcoal, set off by the laptop’s brightness that splashes across the author, as well as the soft glow of the Ancestors and Stars. The author’s eyes are fixed on their belly button which sits in the center of a spiral that spans across their stomach. They are wearing long earrings with a Cowrie shell that dangle close to their mouth. Their hair is piled in a bun spilling over with curls and frizz.

The text on this image reads: “Institutional promises or letters proclaiming these commitments, often responses to demands of recognition, protection, reparation and/or change, very often fall short and continue to reproduce systems of coloniality (with social and economic capital at stake). Pandemic has created an immediacy as well as a cushion institutional place-based and structural violence as they play out in international, interpersonal, and internal struggles. I see in each headline webs connecting to exciting and terrifying scholarship. Surely this is as good a time as ever to be drawing from all of our deep wells.”

Credit:

Sonja Nosisa Noonan-Ngwane

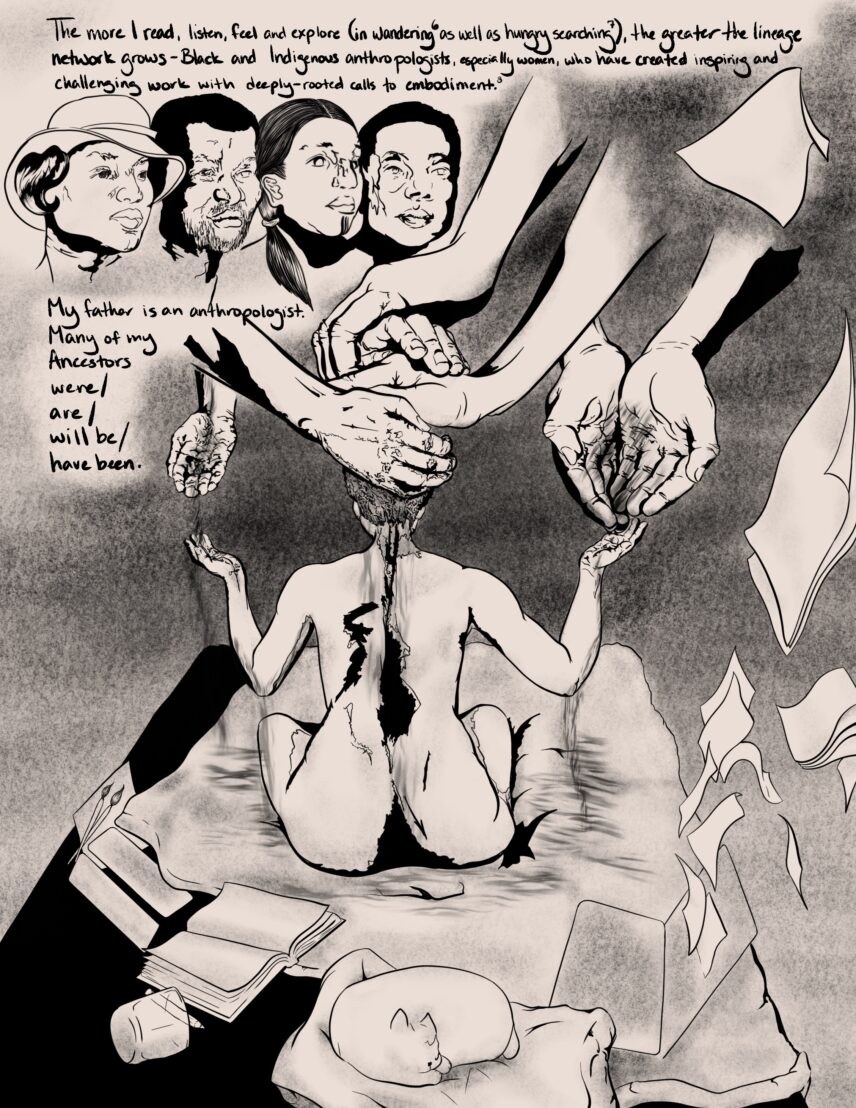

Image description: Busts of four disciplinary Ancestors of anthropology. The first from right to left wears a hat and has short hot-curled hair that pops out from the hat on their right cheek and swoops just below the ear. The second has short afro hair, a long soft gaze and a beard. The third has long straight hair pulled into two ponytails one of which is visible. They have a wide long nose and a tattoo of three lines going from their bottom lip tucking below the chin. The fourth figure has short hair and has their mouth softly pulled to the side. Ancestors’ hands are shown pouring water into the open and upward facing palms of the author who is seated on a bed facing away from the reader, legs crossed. Ancestors also have their hands laid on the author’s head. The bed has a crooked blanket, sketchbook, drinking glass, pencil, brushes, papers, a pillow with a cat sleeping on it, and a laptop with pages peeling from the screen and flying away and out of frame.

The text on this image reads: “The more I read, listen, feel and explore (in wandering as well as hungry searching), the greater the lineage network grows—Black and Indigenous anthropologists, especially women, who have created inspiring and challenging work with deeply-rooted calls to embodiment. My father is an anthropologist. Many of my Ancestors were / are / will be / have been.”

The text on this image reads: “The more I read, listen, feel and explore (in wandering as well as hungry searching), the greater the lineage network grows—Black and Indigenous anthropologists, especially women, who have created inspiring and challenging work with deeply-rooted calls to embodiment. My father is an anthropologist. Many of my Ancestors were / are / will be / have been.”

Credit:

Sonja Nosisa Noonan-Ngwane

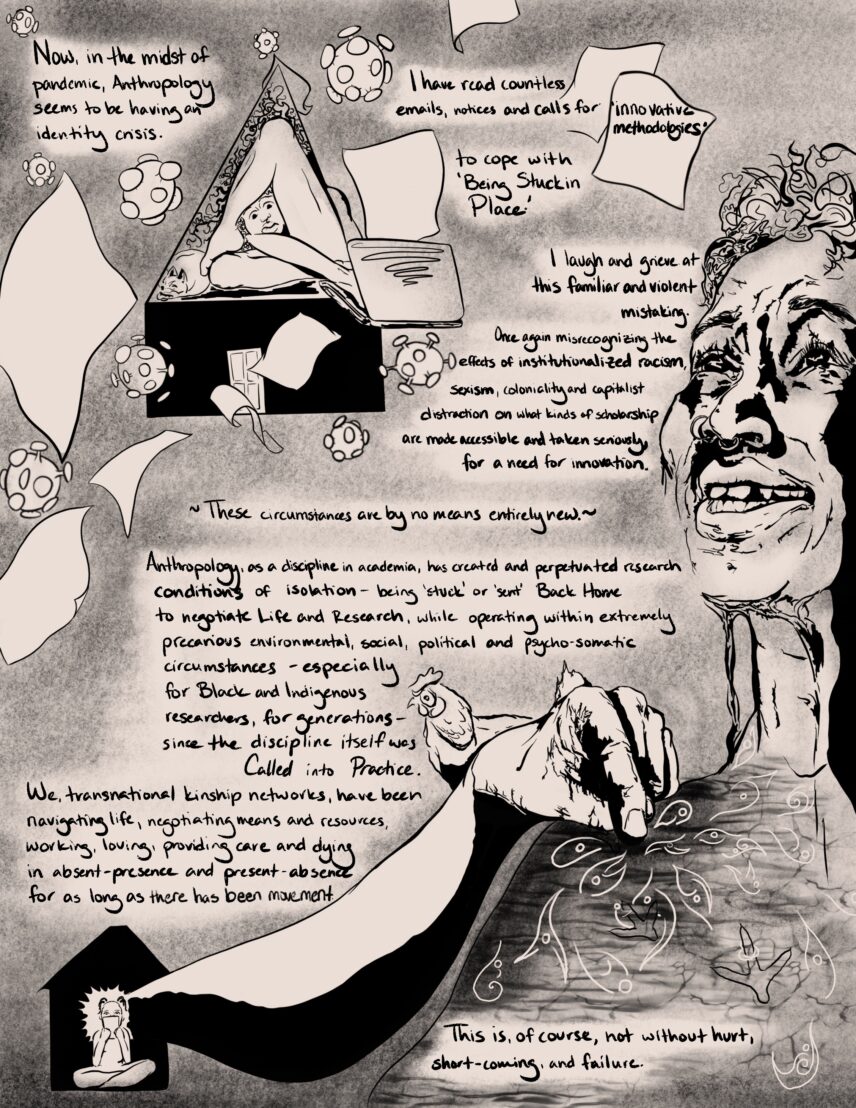

Image description: Author contorts to squeeze into the comically small triangular-shaped attic of a house. Filling most of the space, save for that occupied by the cat curled up and sleeping, the author reaches through the space between their bent legs past their overwhelmed-looking face to reach and type on a tediously-balanced laptop out of which fly papers. Several drawings of coronaviruses dot the area. On the right side of the page, the author is drawn large, looking weepy, overwhelmed, and exhausted with tears streaming down below their neck and pooling where the water looks more like a lake. Beside that, a person in a shadowed house holds a phone that illuminates their face. From their phone extends a long arm that pokes on the shoulder of the author on the right side of the page. Ancestor Spirits spill out dancing across the author’s chest where the water has pooled. There are faint chicken footprints as well. Behind the hand is a chicken.

Text woven throughout the illustration reads: “Now, in the midst of pandemic, Anthropology seems to be having an identity crisis. I have read emails upon emails, notices and calls for ‘innovative methodologies’ to cope with ‘Being Stuck In Place.’ I laugh and grieve at this familiar and violent mistaking. Once again, mistaking the effects of institutionalized racism, sexism, coloniality, and white supremacy on what kinds of scholarships are taken seriously, for a need for innovation. These circumstances are by no means entirely new. Anthropology, as a discipline in academia, has created and perpetuated research conditions of isolation, being ‘stuck’ or ‘sent’ Back Home to negotiate life and research, while operating within extremely precarious environmental, social, political and psycho-somatic circumstances especially for Black and Indigenous researchers for generations—since the discipline itself was Called into Being. We, transnational kinship networks, have been navigating life, negotiating means and resources, working, loving, providing care, and dying in absent-presence and present-absence for as long as there has been movement. This is, of course, not without hurt, short-coming, and failure.”

Text woven throughout the illustration reads: “Now, in the midst of pandemic, Anthropology seems to be having an identity crisis. I have read emails upon emails, notices and calls for ‘innovative methodologies’ to cope with ‘Being Stuck In Place.’ I laugh and grieve at this familiar and violent mistaking. Once again, mistaking the effects of institutionalized racism, sexism, coloniality, and white supremacy on what kinds of scholarships are taken seriously, for a need for innovation. These circumstances are by no means entirely new. Anthropology, as a discipline in academia, has created and perpetuated research conditions of isolation, being ‘stuck’ or ‘sent’ Back Home to negotiate life and research, while operating within extremely precarious environmental, social, political and psycho-somatic circumstances especially for Black and Indigenous researchers for generations—since the discipline itself was Called into Being. We, transnational kinship networks, have been navigating life, negotiating means and resources, working, loving, providing care, and dying in absent-presence and present-absence for as long as there has been movement. This is, of course, not without hurt, short-coming, and failure.”

Credit:

Sonja Nosisa Noonan-Ngwane

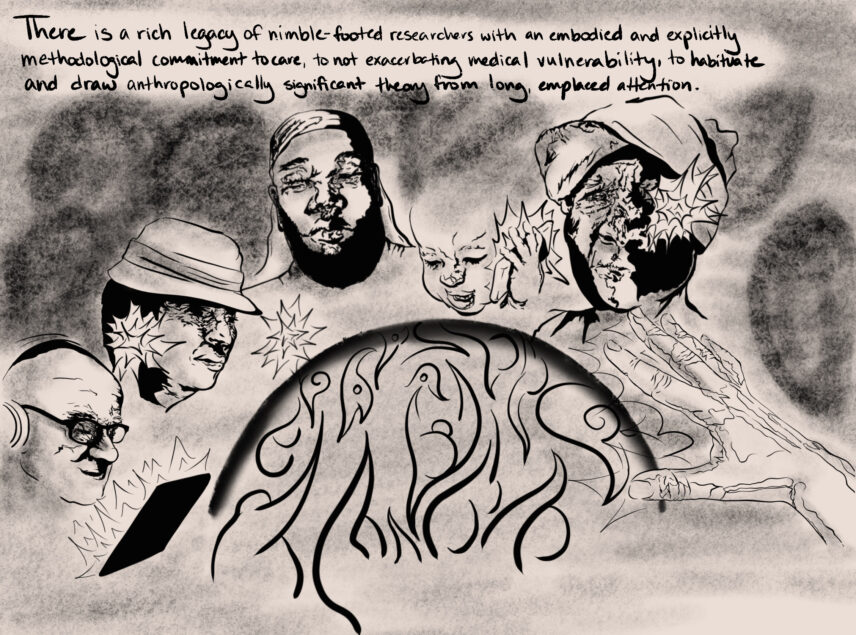

Image description: Five busts and one hand face a globe that swims with Ancestor Spirits. Flare-like lines highlight powerful modes of connection such as information and communication technologies, as well as embodied powers of touch, sight, feeling, and listening. These busts include an Elder holding a tablet wearing headphones with the screen glowing, a person wearing a hat with their ear glowing, a person in a durag with beard listening with eyes closed and heart glowing, a child smiling and pressing a glowing phone to the side of their head, an Elder with a headwrap and eye in shadow that glows, and a hand with the glowing palm facing the Earth. There are shadowed shapes behind the other figures to indicate that there are more People / Spirits Present than are detailed.

The text included in the image reads: “There is a rich legacy of nimble-footed researchers with an embodied and explicitly methodological commitment to care, to not exacerbating medical vulnerability, to habituate and draw anthropologically significant theory from long emplaced attention.”

The text included in the image reads: “There is a rich legacy of nimble-footed researchers with an embodied and explicitly methodological commitment to care, to not exacerbating medical vulnerability, to habituate and draw anthropologically significant theory from long emplaced attention.”