Article begins

Note: Dr. Sabine Hyland acknowledges the suggestion by Dr. Sarah Bennison that there exists a visual similarity between some funerary khipus and umbilical cords. This is an analogy that has been published previously by Mr. Roberto Aldave Palacios, one of the coauthors of the article.

In the peaks of the Andes, fearsome beings called condenados are believed to roam the hills, searching for human prey to devour. Condenados are a “living dead”—people who committed great sins when alive and therefore are unable to pass into the afterlife. According to Central Andean folklore, the only reliable way to defeat a condenado is to grab its khipu—a knotted cord that was used for communication in the Inka Empire—and put it out of reach. Without the khipu, the condenado cannot walk and its intended victim will escape.

The centuries-old custom of making funerary khipus to accompany the dead in their journey through the next world had been dying out in the Central Andes. However, our research reveals that during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been devastating in rural areas, funerary khipus are undergoing a resurgence. Elderly khipu experts who had given up the art have been called out of retirement to create khipus for the dead. Funerary khipus embody narratives about life and death while providing comfort to those who mourn. When made in the proper manner, the knotted cords bestow animacy to the dead; this same power gives the living a way to vanquish those evil beings—the condenados—who hunger for human flesh. In the context of the coronavirus pandemic and the heightened anxieties over death, funerary khipus serve to bring what is an incomprehensible horror—the skyrocketing death rates in the Peruvian countryside—within the realm of ordered understanding.

For over a millennium Andean peoples created khipus to record and transmit both numerical and narrative information. Fashioned from multicolored threads that were knotted and formed into a variety of shapes, khipu usage peaked during the Inka Empire (c 1400–1532). Yet, even after the Spanish invasion in 1532, some highland communities continued to use khipus for storing data about population, labor, crops, livestock, and tribute. Christian khipus inscribed prayers and tallied sins, while narrative khipus encoded secret messages during indigenous revolts. In the Central Andes, khipus were wrapped around the corpse during the wake and interred with the dead. Although funerary khipus have been known to exist throughout the region, until now the only practitioner of this tradition who had ever been interviewed was Gregoria Rivera Zubieta, called Mama Licuna, from the village of Cuspón.

Anthropologists Arturo Ruiz, Magdalena Setlack, Molly Tun, and Filomeno Zubieta Núñez studied the funerary traditions in Cuspón prior to our research. The funerary cords are simpler than most Inka khipus: they consist of a single knotted cord up to six meters in length comprising black (or blue) and white threads. Doña Gregoria would make the khipu during the wake when the deceased’s body was laid out on a table inside the home. As family and friends joined together to mourn, Mama Licuna sat in the patio and created the khipu from thread brought by relatives of the deceased. When the khipu was complete, it was tied around the corpse’s waist, with one end of the cord going down the left leg, and other end down the right leg. There were seven knots on the khipu; four knots for the left leg, and three for the right leg, with a Cross at the end. Doña Gregoria explained that the knots indicated the Hail Mary prayer while the Cross represented the Our Father oration.

The khipu allows the soul of the deceased to walk and to overcome the obstacles and challenges in the afterlife. Roberto Aldave Palacios, who knew Mama Licuna well, remembers that she told him that “the khipu is the road to eternity.” Its presence gives the dead the ability to negotiate all the dangers that they will encounter after death, enabling them to pass to the final resting place where they will become ancestors. Roberto’s unpublished film footage of Doña Gregoria making a khipu shows that she also associated each knot with the words of a Quechua song:

Legs flailing about uselessly,

you are

becoming

an ancient one [machu];

almost the one

who is underneath,

almost really extinguished;

and here at the end is the Cross.

This prayer was chanted in a sing-song voice while she pointed to each knot in turn. It refers to how the khipu strengthens the legs so they will no longer be useless, as the deceased is buried underneath the ground like a seed. Khipus enable the dead to come to life again, as it were, sprouting into their new lives as ancestors.

When Mama Licuna died in 2014, it was unclear whether this tradition of funerary khipus would continue. Our research team, working in nearby villages, has found that not only is the custom still present, but funerary khipus appear to be undergoing a revival during the COVID era. Peru has experienced one of the world’s highest per capita death rates from the disease, which hit elderly populations in the countryside especially hard. Residents in the worst afflicted regions told investigator Marcelo Rochabrun that they have “undergone collective trauma due to the pandemic.” In the early days of the pandemic in Cuspón and the surrounding area, bodies were cremated quickly without any burial rites, adding to the crisis’s emotional toll. Once funerals resumed, villagers in communities like Ticllos took extra care to ensure that their loved ones were buried with khipus. Funerary cords provide a meaningful way to address the devastation and anguish wrought by the pandemic’s era of continual death.

Seventy-year old Taytay Hilario Paulino Idelberto, the khipu maker in the village of Ticllos, has been called upon to use his skills to meet these challenges. (The honorary title “Taytay” means “Father” in Quechua.) As a child he learned the art of khipus from his great-grandfather. Taytay Hilario told us that the khipu empowers him to deal with his sorrow when a loved one dies. “I feel sad when I make a khipu because my relatives and my grandparents are in mourning. This,” he said as he held up a khipu he had made, “controls the grief.”

Taytay Hilario’s khipus have multiple crosses and knots down their entire length. For him, the khipus are a venue for solemn puns and meaningful word play. The khipus help the dead to walk—“camina”—but they are also a road—“camino”—representing the life of the deceased. The khipus accompany—“acompaña”—the dead in the afterlife, while the tassels on the ends are bells—“campanas”—that ring for the dead. He provides no Christianised explanation for the crosses and knots. Rather, each cross represents the Andean concept of “tinku,” where opposing forces join together. This symbolizes the good things that happened in the life of the deceased, while the knots indicate difficulties and obstacles. As Taytay says in rhyme: “The crosses are for passing smoothly—‘pasar’—while the knots are for kneeling”—”rodillar”—that is, for challenges that bring you to your knees.

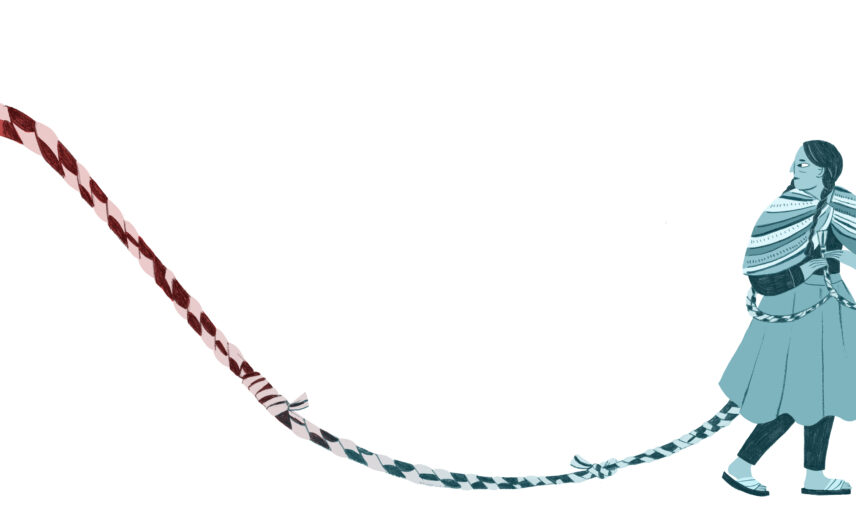

Anthropologist Catherine Allen’s discussion of Andean ideas about death helps us understand why the act of making a khipu can animate the dead in the afterlife and bring succor to the living. The concept of “raki,” Allen explains, expresses an Andean ontology of death. Raki is the “root of words denoting separation or partition of entities that originally belonged together…separation without resolution is raki-raki.” Death is the act of separating things that belong together, of tearing a child or grandparent or mother away from the interconnected web of family and friends forever. “Raki is comparable to the process of separating the yarns of a plied thread—a complex whole being ‘decomposed’ into its constituent parts.” If death is understood as the unwinding of threads that were once plied together, then we can see how the making of a khipu during the wake symbolically rectifies the dissolution of death. The different skeins of yarn that comprise the funerary khipu must be donated by the relatives of the deceased, who help the khipu expert twist and bind the threads together, making a long black (or blue) and white rope reminiscent of an umbilical cord. The funerary khipu is the antithesis of raki-raki; as it is wrapped around the corpse, its interwoven threads give life and movement in the next world.

Just as the khipu provides the dead with the ability to walk, snatching the khipu away from a living corpse will paralyze it, making it unable to wreak its cannibalistic rage upon the living. Mama Milala, an elderly woman from Ticllos, recounted the story of how a woman who lived alone in the mountains was attacked by a condenado. At twilight, when the woman was cooking dinner, a visitor appeared on her doorstep. She invited him inside and offered him food. Yet he merely sat there strangely, without eating, and she became afraid. Realizing that he was one of the living dead, she fled, running down the mountain. The condenado chased her and just as it was about to seize her in a fatal embrace, she ripped the khipu from its waist. “Uff,” it cried, and immediately began to flail about with its arms, unable to move its legs. As she continued safely on her way to the village, she could hear its voice in the wind, calling out “khipu-u-u-, khipu-u-u, khipu-u-u…”

In life, condenados committed terrible acts against others; they raped family members, stole from friends, or hoarded wealth. In other words, they violated the bonds of reciprocity that tied them to those around them. As punishment they must wander the earth, devouring those whom they meet. Martha Rojas Zolezzi, who has studied condenado folklore, says that in Bolivia and Southern Peru the only way to destroy condenados is for people to band together to beat the revenants’ bony skeletons to pieces or burn them to ash. The solution to the threat posed by condenados in Ticllos and neighboring towns is peaceful and elegant: rob the revenant of the khipu that represents its links to the living, freezing it helplessly in place until it collapses into nothingness. In regions with no tradition of funerary khipus, however, there is no possibility of defeating the monster by stealing its burial cords.

During a time of high death rates and trauma, the khipus bring healing to the experts who make them and to the relatives who wrap the cords around the deceased in a final embrace. The presence of the khipus metaphorically enfolds all the survivors, empowering the living, as Taytay Hilario says, to control their grief.