Article begins

A documentary film shows the challenges faced by Soli children as they learn in a language that is not their own. But does the future have to be in English?

“What if the children learned in Soli ? You mean only in Soli? …Without learning through these other languages? Could it happen? Is it possible? We would love that, but can it be?”

This is how Stanford, an elder in the Soli speaking village of Lwimba, Zambia, responded to the idea that his grandchildren could be taught in their mother tongue, rather than Nyanja and English. The translation into English text elides the wishful excitement it provoked in Stanford. But, perhaps it does highlight the desires of the estimated 40 percent of the world’s population (or 2.3 billion people), who lack access to education in their own language, to understand the teaching in their own or their children’s classrooms. And, in turn, to overcome the unfair and unequal educational journey that their children must undertake.

Colours of the Alphabet feature film poster. Tongue Tied Films and Lansdowne Productions

My recent feature-length documentary film-based research project Colours of the Alphabet, focused on issues of indigenous language use and education through the story of Lwimba primary school’s grade one class, aiming to ask global audiences, Does the future have to be in English? The same question would also challenge us to think about how and for whom we would distribute the film.

Learning in English

The film follows Steward, Elizabeth, M’barak, and their families over the children’s first nine months at school, as they slowly come to terms with the reality that their own language, Soli, is no longer what they should speak at school or in most aspects of life outside their home and community. Zambia is home to 72 spoken languages and 7 national languages, but only one official language—English. English is the language of the state and the language of education. Yet, fewer than two percent of Zambians speak English at home. Their teacher, Miss Hangoma, speaks Nyanja—a national language, but one still somewhat foreign to most of the children in class—in an attempt to communicate with the students as best she can. (Like many primary school teachers across Zambia, Miss Hangoma was sent to work in a district where she did not speak the children’s language). To add to this educational mountain facing the children in the film, the curriculum demanded immediate English immersion, in preparation for the transfer to a full English medium education in two years.

Soli does not conform to the common and widely circulated media narrative of a minority indigenous language community fighting for the survival of their “endangered” language.

All of this sounds daunting and unjust, and for Steward, Elizabeth, M’barak, and their 50 classmates, it was. The colonial and post-independence political history of the region, combined with ongoing encroachment of the English language through government policy, media, and technology, further complicate the language ideologies that influence language use in the school and community. The wider inequity and social stratification along language lines that has emerged was also not lost on the parents. M’barak’s mother revealed the pressure she felt when she noted during an interview that it was “a must for him to learn English. In these modern offices everybody uses English. So, if you want a good job here in Zambia, you have to learn English.”

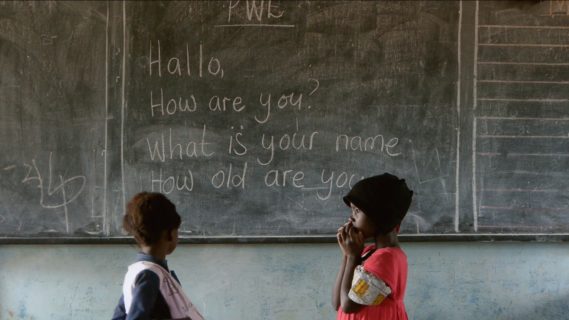

During the course of filming the language ideologies in the classroom played out in myriad linguistic and educational moments ranging from initial struggles for basic communication with the teacher—often through Miss Hangoma’s valiant attempts to speak Soli or via six-year-old interpreters—to the students’ first lessons in learning basic English greetings, which they were told (in Nyanja), “shows respect! Once you ask ‘Hallo… how are you?’ ‘What is your name?’ ‘How old are you?’ That person becomes your friend. Understand?”

Some examples from over 100 hours of rushes are in the final film, others remain in the project archive. It was perhaps, eight months into the year, when students were required learn and sing the English words of Zambia’s national anthem—after a rousing introduction by the teacher on the struggle to overcome colonialism—that their total inability to get close to succeeding reminded us of just how far the linguistic experience of students can be from that imagined by a state.

Steward and his sister in one of their first English lessons. Steward was from a traditional Soli family, one of multiple generations born and raised in Lwimba. He was also a shy, sensitive six-year-old child faced with entering his first year of school not speaking the language of his teacher or the education system. At times the classroom became an overwhelming place to be. Tongue Tied Films and Lansdowne Productions

A global challenge

The film is set within the wider global challenge of the lack of mother-tongue education. Research has found that children not only learn best when taught in their mother tongue (see for example, Bühmann and Trudell 2007; Trudell 2016; Pinnock 2009), but they are also more likely to participate and succeed in the classroom (Kosonen 2005), to enjoy family and community engagement with their education (Benson 2002), and to have increased self-esteem (UNESCO 2016). Learning in one’s mother tongue matters for a student’s educational attainment and for their wider personal development.

This global discussion on minority language rights further complicated the project, especially when it came time to release the film for international festivals and audiences. Soli does not conform to the common and widely circulated media narrative of a minority indigenous language community fighting for the survival of their “endangered” language. As with many minority language communities, the number of Soli speakers is growing, largely through high population growth in rural areas. Elizabeth’s parents note in the film (in Soli) that

Soli does have a bright future. It will be spoken. Until recently, Soli wasn’t heard around Zambia. In town, people used to hide it and you would only hear other languages. But nowadays, even when you are travelling on the bus you will hear people speaking Soli. Now, they are also making a new radio station in Chongwe that will be in Soli, so now we are saying “Soon we will be like white people and true Solis!”

The number of Soli speakers numbers in 1986 were estimated at 54,400 (Grimes 2000) and the most recent census figures note that Solis account for around 0.7 percent of the Zambian population (Zambian Central Statistical Office 2012), or approximately 120,000 people in 2019. Steward is one 16 brothers and sisters, all proud Soli speakers, but all facing the same lack of opportunity to use the language in the classroom at any stage of their education.

An English lesson in the grade one class. The students had English lessons built into their curriculum from the start of grade one, despite most of them not yet fully understanding the teacher’s language of Nyanja. Tongue Tied Films and Lansdowne Productions

The elision and suppression of indigenous languages in formal education extends to resources. Despite growing speaker numbers, Soli speakers have very limited literacy material at their disposal. Elizabeth’s parents tell how “right now, there are virtually no books in Soli. When there are more books, we will teach our children to read in Soli ourselves.” The potential cultural cost of the continued lack of indigenous language education and resources often underpinned conversations with parents; their desire to expand their language’s use in classrooms was also driven by the intangible links between language, history, tradition, and community identity. As Stanford brought into focus, “Soli has a rich history; you learn important traditions through it.” For Elizabeth’s parents, “As long as she knows Soli she will not lose where she comes from.”

The informal use of digital technology has played an increasingly important role in language use over the last decade. Lwimba is no exception. Although there was no running water or electricity in the village when we filmed, Lwimba’s residents have had mobile data coverage since the early 2010s. As a result, digital communication platforms including social media provide a valuable mechanism for Soli speakers to use literacy skills in their own language. Digital technology as a means of supporting indigenous language use would also play an important part in the film’s final evolution—its digital release across Africa.

Releasing the film in African languages

As the documentary film emerged from the research project, the producer Nick Higgins and I realized that although the release of the film in festivals and cinemas fostered fascinating and often emotional audience responses—the experiences of Gaelic and Scots speakers entering school systems in Scotland, Sardinian and Neopolitan speakers contending with Italian medium education, or dialect speakers in China starting out in Standard Chinese primary education—there was an audience of indigenous language speakers across Africa who could directly relate to the experiences of Steward, Elizabeth, M’barak, their families, and their grade one classmates. We needed to reach these audiences too.

“Stand and sing of Zambia proud and free,” sings the teacher, exhorting the class to repeat the independent declaration in the very language of subjugation. Tongue Tied Films and Lansdowne Productions

Together with Africa’s only continent-wide documentary film broadcast platform, AfriDocs, and with the support of a variety of film industry and academic funders and partners, we launched an ambitious impact project to digitally broadcast the film in 30 languages (27 indigenous African languages, plus English, Portuguese, and French) across 50 countries in Africa. This was to be a first for a documentary film; before we could achieve that goal we needed to train 54 indigenous language speakers in translation and subtitling skills. Of the 27 languages into which we subtitled the film, only 12 were languages that YouTube could technically accommodate, let alone provide as content.

On completing the training the subtitlers received the job of creating their language version of Colours of the Alphabet, and also became inaugural members of the Africa Film Translation Network, an online community launched this year. The network aims to provide a platform for other film and media producers to find trained subtitlers to create versions of their work for release in African languages.

Elizabeth (right) walking to school with her neighbors and classmates. Although Elizabeth was one of the highest achieving students in the grade one class, her chances of progressing through to high school were slim. Only five percent of final year students at the school during the year of filming gained grades high enough to continue directly on to high school. Tongue Tied Films and Lansdowne Productions

Colours of the Alphabet launched in 30 languages on International Mother Language Day, 2018. The film was made available free-to-view via the AfriDocs digital platform, with support from a social media campaign encouraging viewers to share their own stories of language and education under #mytonguemystory. As a filmmaker, witnessing the sharing, comments, and stories that emerged was heartening. This was where the stories of Steward, Elizabeth, and M’barak began to reveal themselves as resonating with generations of African language speakers across the continent. As Wisdom Koffi, from Adjawlo, Ghana, shared (in Ewe):

My story is not that far off from Stewards. I grew up and went to school in a community where it was difficult to communicate due to the fear of making a mistake. We were punished if caught speaking Ewe at school. I remember a few of my classmates were fortunate enough to have parents that spoke French at home; those kids were able to reach the teacher’s expectations. I spent three years in the same grade due to failing exams. I know I would have done better if I had been able to study in my mother tongue.

Perhaps the final words are best left to Abel Dzobo, a chiJindwi speaker from Zimbabawe, who noted in his own story, “Mwana wose anofanirwa kudzidza norurimi rwaamai vake, kwete kupiwa mumwe mutauro, zvinoita kuti uite seusina kukosha, uhu hutsinye uye zvinovhiringidza kwazvo” (Every child should learn in their real mother tongue, not to have another dialect foisted on them; it’s so demeaning, so unjust, and so confusing).

Alastair Cole is a documentary filmmaker and lecturer in film practice at Newcastle University, the United Kingdom. His film-based research explores subjects surrounding multilingualism, language ideologies, and audiovisual translation. You can see more about his research on the Tongue Tied Films website. He tweets at @TongueTiedFilms.

The film was produced by Nick Higgins, professor, director of the Creative Media Academy, and chair in media practice in the School of Media, Culture, and Society at the University of the West of Scotland.

You can watch Colours of the Alphabet (video on-demand) in eight languages on the film’s website or purchase the DVD through Documentary Educational Resources. If you live in Africa, you can view the 60-minute version of the film for free in one of 30 languages at AfriDocs.

Cite as: Cole, Alastair. 2019. “Language Lessons.” Anthropology News website, September 19, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1261