Article begins

This piece includes an image of a clay effigy of a woman bound and pierced as part of a fourth-century erotic spell.

The practice of magic thrived in classical antiquity. From Athens to the Black Sea to Roman Britain, from tavern goers to the highest-born imperial nobles, magical texts and objects flourished as modes of managing vulnerability, overcoming rivals, mitigating loss, and surmounting uncertainty. Ritual practitioners—professional magicians—peddled various charms, custom-made spells, curses, and initiations for the ancient customer in need.

Writing around 375 BCE, Plato would describe the traffic in magical goods and services in classical Athens, including the use of incantations and bindings spells and the unease felt by passersby on seeing “molded wax images,” types of magical curse-effigies, placed at doorways, crossroads, and ancestral tombs. Over 500 years later, the Latin writer Apuleius would render, in vivid detail, a scene of a witch at work:

First she arranged her deadly laboratory with its customary apparatus, setting out spices of all sorts, unintelligibly lettered metal plaques, the surviving remains of ill-omened birds, and numerous pieces of mourned and even buried corpses: here noses and fingers, there flesh-covered spikes from crucified bodies, elsewhere the preserved gore of murder victims and mutilated skulls wrenched from the teeth of wild beasts. Then she recited a charm over some pulsating entrails and made offerings with various liquids.

Coming from different literary genres—a Greek philosophical text and a Roman novel—these accounts reveal the presence and potency of magic in classical antiquity, and the centrality of objects within such ritual practices. Magic included not only spoken words, gestures, and actions, but was also expressed by way of physical, material forms, such as curse tablets, effigies, amulets, and gems, to name but a few. Many of these objects have survived in the archaeological record to reveal that classical communities used ritual to conquer fear and uncertainty, to influence individual lives, to improve current circumstances, and to transform the future.

Put a spell on you

The magical materials used by Apuleius’s witch included tablets inscribed with curious letters. Thousands of these so-called curse tablets have been found in locations stretching from Roman Britain to Egypt to the shores of the Black Sea. They contain spells, prayers, and curses aimed against lovers, politicians, charioteers, tavern keepers, craftsmen, enslaved persons, sex laborers, and just about everyone in between. The Greeks called these objects katadesmoi (κατάδεσμοι), “bindings down,” while the Latin term for them, defixiones, translates into English as “curses that fix or fasten someone.” Binding curses were often utilized in moments of great anxiety, high-stakes situations, as ways of managing competition and vulnerability—a business rivalry, a legal trial, an athletic contest. Curse tablets and other ritual objects were created by both amateur curse writers—you, me, and that nasty coworker of yours—and ritual professionals, persons with expertise in the sale of spells, charms, curses, and purifications.

After a binding curse was inscribed on the thin lead tablet, the object was then folded or rolled up, pierced with a nail, and deposited in a grave or a well or a fountain (figure 1). Such subterranean sites effectively served as spatial conduits, carrying the incised object to the realm of the dead and underworld divinities, who, as sources of agitated or mercurial energy, could bring the curse to pass. Sometimes the process of casting of a curse or binding spell in antiquity could include collecting little bits of the target’s person, such as strands of hair or fingernail clippings, and then manipulating these bits to focus the curse against that specific victim. A third-century CE curse tablet from a well in the Athenian Agora, for example, contained several strands of waterlogged long brown hair, which likely assisted in directing the spell at the woman Tyche, who is named as the intended target. We know of other lead curse tablets that were interred with wax, wood, and clay effigies, for example. Clearly the act of incising the curse onto lead was just one part of a much larger ritual process.

A corpse for a curse

Why deposit a curse in a grave? In many cases, the deceased was unknown to the ritual practitioner. The corpse simply served as a vehicle for conveying the curse to the powers of the underworld, who would then bring it to pass. There is also evidence from the fourth century BCE that some practitioners understood the spirit of the dead person, an entity which could linger and remain active around the grave after burial, to enact the malediction. In both scenarios, the dead were understood as agents that could affect the curse when ritually harnessed, either as purveyors to chthonic underworld powers, or as unquiet forces themselves capable of intervening in the affairs of the living.

Certain types of dead persons held particular appeal in curse rituals, as their souls were deemed exceptionally restless and volatile; the graves of such individuals were especially ripe for supernatural exploitation. Among these groups were aōroi, individuals who died before their time (examples could include infants, children, and women who died before childbirth), and biaiothanatoi, those who died by force or violence. For both groups, the abrupt time or manner of death meant that they had perished unfulfilled, falling short of a standard life cycle; their ghosts were thus particularly agitated and vengeful. One small child’s grave from the Cycladic island of Paros yielded a lead curse effigy dating from around 400 BCE. The figurine was pierced with seven iron nails, the arms were bound behind the back, and a lead collar shackled the neck. Inscriptions on the body in the local Parian alphabet suggest that the object targeted a man named Theophrastos (figure 2).

A second, larger grave in the Athenian Kerameikos contained a lead figurine, the right side of which was inscribed with the name Mnesimachos. The figurine’s arms were twisted behind the back, and the object had been encased in a small lead coffin inscribed with nine personal names and the concluding phrase “and anyone else who is either a legal advocate or a witness with him,” revealing that this assemblage was created on account of litigation in the Athenian law courts. The grave selected for deposition was striking, according to archaeologist Jutta Stroszeck. Ceramic roof tiles were used to cover an adult whose thighs, pelvis, left arm, chest, and spine had been severed and placed at the head of the deceased: a rare type of burial (maschalismos) in which the extremities of the deceased were severed and, at least in theory, placed under the corpse’s armpits to prevent the dead from mobilizing to take vengeance. The effigy of Mnesimachos emerged at the detached pelvis of the corpse. Here the violent death and interment of the deceased afforded an ideal context for the deposition of an inscribed curse assemblage.

A cache of five Greek curse tablets was found in an Athenian pyre grave containing the cremated remains of a young girl, another individual who had perished before her time. Created around 375 BCE, the five tablets attack male-female couples, and were inscribed with similar binding curses. One of the texts, which is representative of the other four, reads as follows (figure 3):

Hekate Chthonia, Artemis Chthonia, Hermes Chthonios: envy Euphiletos, himself and his wife, and their property and household! I bind my enemy in blood—Euphiletos—and ashes, together with all the dead. Nor will the next four-year cycle release you. I bind you in such a bind, Euphiletos, as strongly as possible, and I strike in a kynoton upοn [your] tongue!

These curses open by addressing Hekate, Artemis, and Hermes as a chthonic or sub-earthly triad. Deities with underworld associations were appealed to in binding curses, especially for tablets deposited in underground conduits such as graves and wells. The agent then commanded these deities to do their bidding, to bind, debilitate, or harm their enemies. Some parts of these binding spells are metrical, which suggests that they once circulated orally. The clear, crisp script, careful handwriting, dactylic hexameter, epic language, and repeated formulae suggests that this cache of spells was composed by a ritual professional, someone quite literate and skilled in the craft of curse writing.

An abundance of curse tablets stemming from law court cases shows that they were also performing curse rituals to increase their chances of success.

Trial and execration

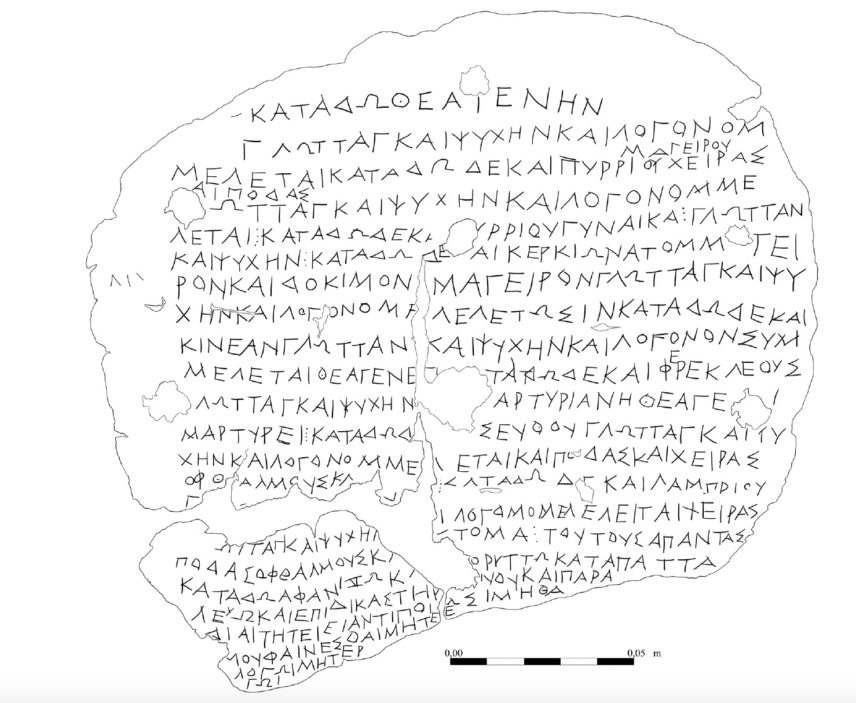

The largest numbers of Greek curse tablets hail from Athens (more than 520 lead curse tablets are known today), and the majority date from the fourth century BCE. Many relate to trials in the law courts. We know from literary sources, namely the Attic orators, that Athenians were hiring speech writers to help persuade and sway juries to their side in trials; an abundance of curse tablets stemming from law court cases shows that they were also performing curse rituals to increase their chances of success. Another curse tablet from fourth-century Athens, for example, curses chefs (figure 4):

Theagenes the cook. I bind his tongue, his soul and the speech he is practicing. Pyrrhias. I bind his tongue, his soul and the speech he is practicing. I bind the wife of Pyrrhias, her tongue and soul. I also bind Kerkion, the cook, and Dokimos, the cook, their tongues, their souls and the speech they are practicing. I bind Kineas, his tongue, his soul and the speech he is practicing with Theagenes. And Pherekles. I bind his tongue, his soul and the evidence that he gives for Theagenes. All these [i.e., their names] I bind, I hide, I bury, I nail down. If they lay any counterclaim before the arbitrator or the court, let them seem to be of no account, either in word or deed.

This curse tablet was occasioned by a conflict between professional, popular cooks (ancient celebrity chefs), which had progressed to trial in the law courts. It aimed to impede the legal opposition by binding the rival litigants, their tongues (shorthand for their faculties of speech), souls, and testimonies in court. The curse even took care to target the wife of one of the opposing litigants ahead of the trial.

Effigy of desire

Another effort to bind and curse someone is represented by a small clay effigy of a woman, which has been dated to the fourth century CE (figure 5). The ensemble probably came from somewhere in middle Egypt and was purchased by the Louvre Museum (Inv. 27145a). The clay effigy was discovered inside a ceramic vessel; as though a captive, the figurine kneels with her arms tied behind her back and her feet bound together. The figure’s body had been pierced with 13 pins: one in the mouth and each eye, one in the head, one each in the vagina and anus, one in the chest, one in each ear, and one in each hand and foot. An inscribed lead curse tablet was then wrapped around the nailed figurine, and both were sealed in the pot. The inscription reveals that this elaborate curse was created to erotically attract a woman named Ptolemais to Sarapammon, a man who was obsessed and infatuated with her. Sarapammon’s curse sought to prevent Ptolemais from eating, sleeping, and having intercourse with anyone other than him; the curse violently demands:

Do not allow her to have intercourse with another man, except me alone. Drag her by her hair, by her guts, until she does not stand apart from me!

By binding the arms and legs of her effigy and then piercing it over and over again, Sarapammon seeks, through sympathetic or analogistic magic, to bind her and command her, and to control her mind and body. Combined with texts from the Greek and Egyptian magical handbooks, some of which also carry recipes for creating such effigies and curse tablets, we can begin to understand how someone in Greco-Roman Egypt went about casting an erotic spell, and addressed feelings of intense desire, lust, and exasperation over 1,800 years ago.

Fowl play

In the summer of 2006, excavators at the Athenian Agora uncovered an unglazed ceramic cooking pot dating to around 300 BCE buried in the back corner of a workshop in a commercial and industrial building (figure 6). The vessel, inscribed with more than 30 names on the exterior and pierced with an iron spike, was found to contain the head and feet of a chicken (figure 7). The object is of interest for the light it sheds on the importance of organic materials within ritualized magic, smack in the heart of ancient Athens.

This binding curse may have stemmed from an impending court case or a conflict between craftsmen; the sheer number of names on the pot intimates that the list could plausibly consist of one party in an Athenian court case, along with witnesses and supporters. The pot’s archaeological context suggests that the circumstances of its burial may have been a conflict between craftsmen associated with the commercial and industrial building. While most binding curses were deposited in graves or bodies of water, some were placed in a location by which the intended victim or victims were likely to pass. The vessel may have been buried in the workshop to harm its occupants, one or more of the people whose names appear on the pot.

There is no evidence of butchering or burning on the bones, so the chicken seems to have been decapitated and dismembered by wringing or twisting while still alive or after its death. Even the smallest bones of the head and feet are present, suggesting that the body parts were still sheathed in skin when they were tossed into the pot.

A later curse tablet from Roman Carthage in North Africa mentions a bound rooster when cursing the leader of a rival chariot team:

[B]ind every limb and every sinew of Victoricus, the charioteer of the Blue team…and of the horses he is about to race…. Bind their legs, their onrush, their bounding, their running, blind their eyes so they cannot see, and twist their soul and heart so that they cannot breathe. Just as this rooster has been bound by its feet, hands and head, so bind the legs and hands and head and heart of Victoricus, the charioteer of the Blue team, for tomorrow!

This text shows that bound and mutilated animals, especially chickens, were used in Roman curse rituals. The chicken curse pot from the Athenian Agora provides much earlier evidence for this practice in communities of mainland Greece.

Grasping at certainty

Our brief foray into the world of magic has revealed the presence of spells, ritual dolls or effigies, and curses from across the ancient Greek and Roman worlds. To some extent, the field of Classics tends to focus on big institutions and phenomena: Athenian democracy, the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars, the Parthenon and the Roman Colosseum, and generals like Pericles, Alexander the Great, or emperors like Augustus and Constantine. What is surprising and exciting about these magical objects is how they collapse the time and distance separating us moderns from the ancient Greeks and Romans, revealing the universally human desire to manage vulnerability and edge out competition, from rival chefs to aloof love interests to opposing litigants at trial.

Yet these types of ritual texts and objects—and their great popularity for some 1,000 years—reveal a far messier, intimate, and interesting view of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Curses, spells, and incantations were used by individuals in ancient Greek and Roman communities to cope with conflict, vulnerability, competition, anxiety, desire, and loss. These rites were intended to change and transform the present and future course of affairs; they were grounded in worldviews in which ritual speech and action were understood to achieve real goals and assuage real fears. Such practices remained prevalent in the classical Mediterranean and well beyond for nearly a millennium. And it isn’t clear, to me at least, that these rituals were ultimately ineffective within the communities in which they were performed and circulated.