Article begins

We all know mosquitoes suck, right? But they literally do! The annoying welt on your arm is not a result of a mosquito bite, but a mosquito suck. Female mosquitoes draw blood to nourish their eggs. In this way, like humans, they care for their young.

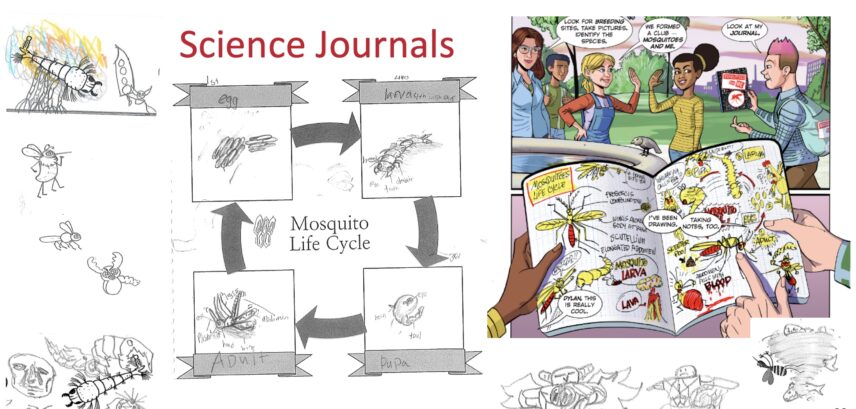

This was one of many surprising facts learned by youths who attended our Mosquitoes & Me summer day camp. Facts like these nurtured their interest in science but also promoted an understanding of nature’s interdependent web of which all creatures, including the little and loathed mosquito, are an integral part.

A 2022 recipient of an Engaged Anthropology honor inspired by the work of Setha M. Low, I see her dual commitments to engaged anthropology and place-based approaches to culture informing the much-needed work of public science communication. Low’s work reminds us that engaged anthropology takes many forms, among them public education. It also urges us to conceive of the public in terms of the particularity of the sociohistorical influences that construe a place and its embodied space. While Low may be surprised, and pleased, I hope, that I am connecting her anthropological commitments to an entomological project, both are, in fact, essential in addressing challenges we face in living with our species’ most pesty and pernicious predator—the mosquito.

Climate change is altering mosquito habitats in ways that make community participation in control and prevention imperative. Cities in warmer regions of the United States are experiencing higher rates of mosquito-borne disease, suggesting that mosquitoes and their pathogens are adapting to climatic temperature shifts. But this risk is particular; it varies by neighborhood. Mosquito samples collected from less-wealthy areas, ones characterized by infrastructure issues such as abandoned structures and inadequate waste management, have more and larger mosquitoes than wealthier areas. If, as research suggests, larger mosquitoes live longer, then people who live in less-wealthy areas may be at greater risk of mosquito-borne illness.

The CDC has warned that the need for mosquito control is beyond the capacity of public health departments. Part of the challenge is that some mosquito breeding grounds, like garbage bins and leaky outdoor faucets, are in spaces only accessible by residents. While others may be more publicly accessible, like puddles in community gardens or tire swings in parks, they still require community participation because the need for surveillance in these spaces exceeds the capacity of public health offices. This poses the question, How do you cultivate a local sense of public health responsibility when scientists, like entomologists, are not trained in translating their specialized knowledge to everyday audiences?

From 2016 to 2022, I collaborated with a scientist on an NIH Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA) project focused on urban ecosystems. This focus had dual meanings: my colleague, a medical entomologist, was interested in the urban ecosystem as a site of mosquito-human interaction, including control and prevention, and I, an educational anthropologist leading a university-school-community promise partnership program serving two elementary schools in Des Moines, was interested in the local urban ecosystem as a site of aspiration and attainment with respect to college-going. Working together, our purpose was to use the theme of mosquitoes and public health to enhance the teaching and learning of science in the partner communities, especially empowering young people to be local agents of health and education change. From our experience delivering two-week summer day camps, afterschool programming, family outreach events, and school-based professional development for teachers, we created the Mosquitoes & Me curriculum. In 2022, drawing on activities with a subset of Mosquitoes & Me youths enrolled in a weekend Comic Book Club, we published the comic Mosquitoes SUCK! as a way of amplifying public education around the critically important but not widely understood content of mosquito science. Science comics, we believed, provided one answer to the complex science translation question.

In and of itself, using science comics for public science communication is not necessarily noteworthy. Research, for example, has documented the effect of visual features on cognition. What is noteworthy about Mosquitoes SUCK! isthe way that it reflects its origin in the place, people, and purpose of our larger urban ecosystems project. It is infused with the place-based, engaged anthropology values that the Setha M. Low Engaged Anthropology Award promotes.

There are four steps to the robust creation of comics for public science communication. First, the narrative has to be driven by a clear conceptual foundation. Second, the narrative has to be grounded in a scientifically relevant setting. Third, engaging characters must move the narrative forward. Fourth, these first three steps need to work together to advance a compelling storyline.

Clear conceptual foundation

We designed the Mosquitoes & Me curriculum around the Ambitious Science Teaching framework. This framework encourages the use of overarching questions that, without easy answers, promote wonderment and thus launch learning as a form of collective adventuring.

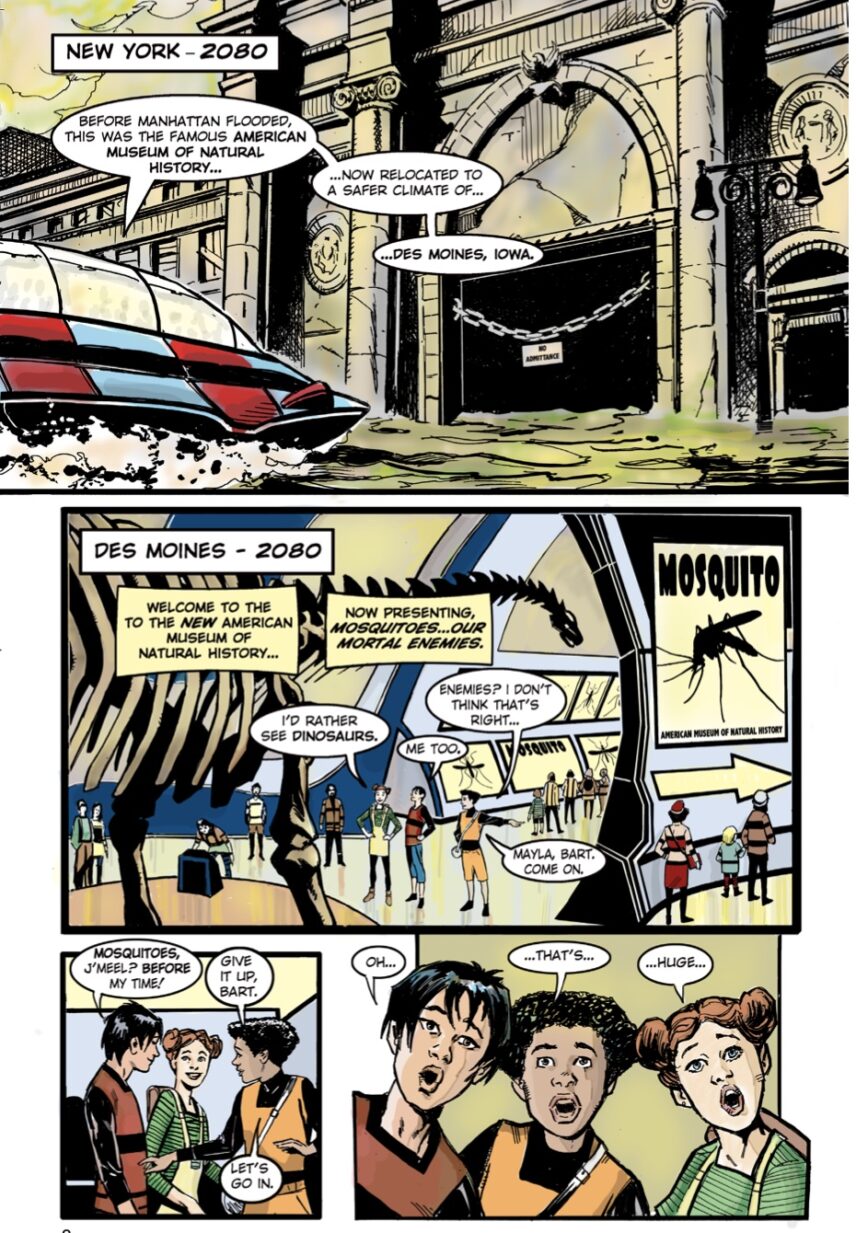

Riffing off the title of one of the earliest books on mosquito control and prevention, Mosquito or Man: Conquest of the Tropical World, we decided to launch summer camp learning with the question, In an end-of-world battle, who would win—mosquitoes or humans? First, campers worked in groups to come up with their best guesses and supporting reasons. Next, we discussed their initial ideas and asked what more would they need to know in order to confirm or negate their original answers. The dystopian premise of Mosquitoes SUCK! in which, by the year 2080, mosquitoes have been eliminated by humans, disrupting the interconnected web of life, is a direct reflection of the learning launch that propelled all future camp conversations as part of its unfolding curriculum.

Scientifically relevant setting

We then clustered the ideas generated by campers’ brainstorming into four conceptual categories of biology, ecology, disease transmission, and control and prevention. These four conceptual categories became the units organizing camp content and are now reflected in the final Mosquitoes & Me curriculum as well as Mosquitoes SUCK!

In setting the stage with its dystopian premise, the reader is introduced to a futuristic teenager and her friends. In this 2080 context where mosquitoes have been eradicated with ecologically unfriendly methods, this teen recalls her grandmother’s (failed) advocacy for a coexistence-centered approach. The comic’s narrative then travels back in time to a point (the year 2020) where different approaches to mosquito control could have averted ecological collapse. The learning that emerges from the narrative centers the idea of mosquitoes and humans living together interdependently. The discursive move from conquest (“Mosquito or Man”) to coexistence (“Mosquitoes & Me”) makes relevant the critical need noted in the mosquito science literature for the everyday participation of residents in community-based public health efforts.

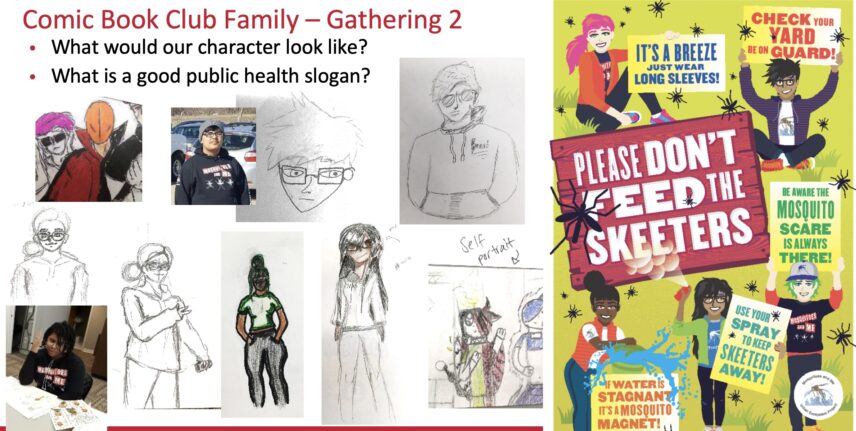

Engaging characters

In the time travel narrative, we see the grandmother as a young girl. Tiara is attending a 2020 Mosquitoes & Me summer camp. We see her observe a blood feeding and learn about why mosquitoes (actually) suck. We also see her do larval dipping at a park and learn about mosquito breeding grounds in city spaces. An illustration shows a camp peer showing his lifecycle observations from his Mosquito & Me science journal. The racially/ethnically and gender diverse images of Tiara and other characters engaging in these camp experiences are inspired by and in some cases directly reflective of drawings and ideas offered by the young campers themselves. For example, at the comic’s end is a page with some camp characters holding up public health messages about mosquito control and prevention. These messages were written by Comic Book Club participants, and their characterization is drawn from their own self-imaging. In this way, the characters and activities of Mosquitoes SUCK! represent the young people who inspired its creation.

Compelling storyline

At the beginning of Mosquitoes SUCK!, a group of youths, among them the futuristic teenager we now know as Tiara’s granddaughter, is standing in the relocated Museum of Natural History. It has moved from New York City to Des Moines because of coastal climate disaster. Holographic images of mosquitoes—which these young people have never seen before because they’ve been eradicated by ecologically unfriendly methods—swirl around them. This sets up the intent of the information that the comic provides, that of helping us avoid such a future. Reference is made to points in the past where eradication-focused science of the time led us astray, centering the importance of an interdependent approach to human-mosquito interaction.

This is also how we end the summer camp, with a conversation about how to use what has been learned at the global, national, community, and individual level to be a positive purposeful contributor to mosquito public health efforts in ways that protect the people and other living beings on the planet, and, in so doing, the planet itself.

We had much fun delivering Mosquitoes SUCK! to the young people with whom we worked and having them find all the “easter eggs” about their Mosquitoes & Me experience hidden within its pages. The the most natural way to make science engaging is by starting with the place-, people-, and purpose-full world of the learner.

Complimentary copies of Mosquitoes SUCK!, along with the Mosquitoes & Me curriculum and supporting resources, are available for science education purposes. Send an email to [email protected].

Tricia Niesz is section contributing editor for the Council on Anthropology and Education.