Article begins

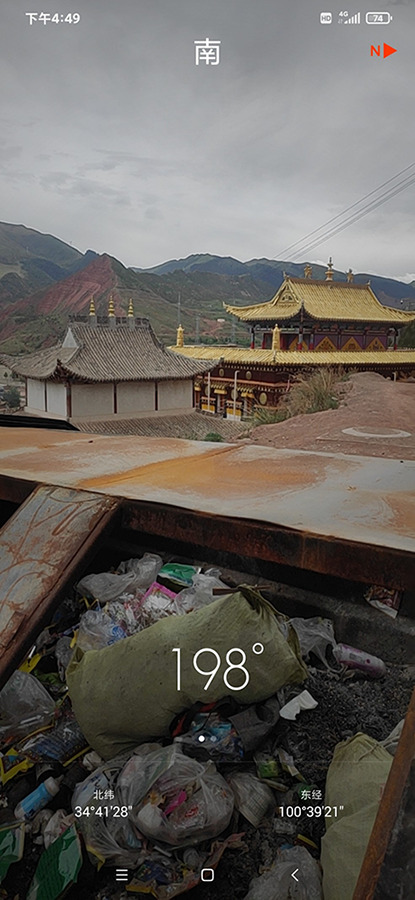

Even those least familiar with Qinghai would be shocked by the scene of waste burning all over the province. Most evenings by the Winter Gecuo Na Lake, “the sacred lake” for Tibetans, fires are lit inside rusty dustbins, burning plastics, papers, foods, metals, and animal remains into ash. Smoke spreads in the air before being swallowed by the blue sky. Toxins sediment into the ground and are slowly absorbed by the soil. Home to Indigenous Tibetans and source of the Yellow, Yangtze, and Mekong Rivers and called the “water tower of Asia,” Qinghai was once portrayed by the poet Hai Zi as a pure, pristine heaven. Yet residents describe a life of smoke and foul smells. As environmental activists captured in their survey of the locals, “We are living in a gas room. Such strong stenches make me dizzy. We never dare to open the windows.”

And yet the issue of piling waste in Qinghai has remained largely unseen by the public. For one, only a small proportion of waste is produced by locals; the majority is left by domestic tourists, who neglect their behaviors’ long-term impact and how these undesirables flow back into their own cities via water, air, and soil. Without a proper waste management system, Qinghai residents often resort to Tibetan customs and burn the unaddressed waste. But, unlike the clean spaces created by burning fallen tree leaves, incinerating modern materials like plastics and metals pollutes the environment further, rather than purifying it.

The two conflicting portrayals of waste in Qinghai by state media and grassroots activists show how the issue’s visibility is actively contested. On the one hand, the state’s recent politico-ecological agendas have reinforced Qinghai’s image as “heaven.” In 2015, the Three-River-Source Park was chosen a pilot site for China’s ambitious National Park project, and in 2021, it was made an official one. State channels such as CCTV have created four celebratory documentaries on Qinghai in just the past two years (e.g., Qinghai: Our National Park). Such promotion of Qinghai as a place of “pure[ness], innocence, and eternity” makes it hard to openly discuss issues like waste, rendered invisible in circulating images of Qinghai despite its devastating impact on the ground. On the other hand, environmental activists, artists, and NGOs (e.g., Snowland Great Rivers Environmental Protection Association and Green Rivers) have been countering the state’s agenda by making Qinghai’s waste issues visible to the general public.

“Waste Qigong” as a new daily norm

“People live on breath, in each breath hides garbage / In Qinghai, from south to north, toxic gas follows you /… / People produce waste, waste produce toxic air / stink, stink, stink / poison, poison, poison / … / one year, five years, ten years, years after years.”

―Lyrics from “Waste Qigong” by Bing Huang (translated by the author)

In the summer of 2021, a group of musicians arrived in Qinghai for a special performance, as one stop on their “2021 Heavy Metal Countryside Tour.” Heavy metal bands were invited to tour the country’s most polluted areas, their audience local villagers and viewers watching the live stream online. The band’s slogan was, “Breathe heavy metal air, listen to heavy metal music!” By linking heavy metal toxins with a musical genre, the musicians combined their performance with environmental activism, critiquing the exploitative nature of China’s industrial development and proposing a new way of taking immediate, public-facing actions.

Tian Xi, a key figure in the project, was a tourist business owner in Qinghai for many years. As a semi-local, he identified waste discarding and burning as Qinghai’s most severe and urgent crisis, which inspired the flash composition of a song titled “Waste Qigong.” Intended as a pun on Qigong, a traditional healing practice combining breathing, meditation, and bodily movements for balance and peace, “Waste Qigong” indicates how breathing waste has become a new daily norm, poisoning Qinghai residents. “People live on breath, in each breath hides garbage,” the song repeats. Bing Huang, the lyricist, explained her creative intentions in our interview, “Qigong is systemic. And waste management should be as well…. But in Qinghai, this system involves no public discourse or voices from below. I use Qigong to critique this irony.” Surrounded by rank grass and in front of piles of rusty trash bins, the musicians performed with their hazmat protection suits on and gas masks covering their faces.

What influence can this experimental performance have? While Nut Brother, the well-known performance artist who initiated this campaign, achieved remarkable success in the Xiaohaotu water pollution case, he understands the unpredictability of practicing activism in China and embraces the strategy of taking “one step at a time.” Online forums are one avenue where further conversations can take place between those committed to keeping this movement forward, slowly yet daringly. On one forum, an anonymous user writes, “I don’t know what kind of spirits sustain their actions. How many, among 1.4 billion Chinese citizens, can do this?” In the chat group maintained by Nut Brother, people from diverse backgrounds, including Chinese diaspora communities, ask, What does Qinghai need (funding or human resources)? Who should be responsible for waste management (the state or citizens)? What can we learn from other countries’ waste governance models? Answers diverge, unsurprisingly. But the bottom line is, one member writes, “to increase exposure and draw the public’s attention;” another echoes, “we need to offer support, engagement, and advice, as a collective.”

Tian Xi’s fieldwork and stumbling blocks en route

Bridging music and activism to raise public awareness isn’t new, and one may be reminded of The Beatles and Bob Dylan in the 60s, or Radiohead and Bruce Springsteen since the 80s. Yet Nut Brother has added his own flair to the tradition by initiating what the group calls “fieldwork heavy metal (tianye zhong jinshu),” meaning that field research lays the foundation for his themed performances. Specifically, Bing Huang’s lyrics are based on two months of ethnographic investigation conducted by Tian Xi. Tian did his fieldwork while regularly interviewing locals, observing their daily interactions, sampling 20 kilograms of toxic chemicals, and documenting scenes of waste running amok.

Despite his familiarity with Qinghai and years of experience in activism, Tian’s fieldwork was full of stumbling blocks. Running out of funds, Tian experienced days with no food or gas. Spotted by local security staff, he had to deal with threats and physical violence. But what concerns him the most are the conditions of doing environmental activism in today’s China. Activist projects involve constant negotiations of what can be done and how to reach that end when such actions are inevitably conditioned by political dynamics that penetrate daily life. In their proposal stage, Nut Brother and Tian tried to seek funding from established environmental NGOs who showed interest in their project. But the plan was rejected for being “too radical” in its aims to expose ecological and human costs by economic development of local industries (see Chen Gang’s Politics of China’s Environmental Protection for discussion of the challenges facing Chinese ENGOs). On other occasions, Nut Brother had to turn down enthusiastic sponsors because having “western” connections could make their projects and those involved vulnerable to accusations of colluding with anti-Chinese powers. When international rivalries are broadly defined and perceived, nationalist sentiments may quickly translate into vehement attacks on social media.

In today’s mainland China, grassroots activists face increasingly limited choices for what can be done. Under these circumstances, as shown by the essay collection edited by Peter Ho and Richard Edmonds, figuring out how to change tactics is simply the norm or necessity. According to Tian, in the “environmentalist community (huanbao quan),” one unspoken rule is that “one shouldn’t intervene in environmental affairs close to one’s home.” By “home,” Tian means the province in which one’s residence is officially registered in the hukou system and thus the judicial authority one is subjected to. In Tian’s case, he isn’t registered in Qinghai; even if he was identified as “suspicious,” Qinghai’s government might be deterred from taking significant actions against him because of the complicated inter-province extradition process. Centralized power ironically provides a shield for non-locals like Tian. Reporting a chemical plant miles away in one’s own residential area would be more dangerous than flying hours to investigate issues in other provinces, he explained.

Our long interviews were filled with Tian’s resolutions and witty remarks as well as feelings of disorientation: “Born in the age of ‘reform’ (gaige) and growing up in the wind of ‘opening up’ (kaifang), our generation was told the country was prospering and moving up… Now the world is pushed frantically by something invisible and powerful. It’s sliding to the abyss, and you’re on the train rushing to that end. Other than screaming in horror, what can you do?” From Deng Xiaoping’s “development as the top priority” to Xi Jinping’s “ecological civilization” agenda, just how much so-called progress has been made and in what sense remains an open question. Over four decades of changes in China, one thing that hasn’t changed is the oppositional framing of economic interests against environmental ones in most development practices. This is manifested in today’s Qinghai: the state sells Qinghai’s image as “heaven” to boost tourist revenues at the expense of actual environments by obfuscating issues such as waste. Grassroots activists experiment with strategies of exposing and mobilizing in their restricted positions.

In archiving these frontline efforts, it’s important not to heroize any activist practices on the one hand and on the other not to assume the repressive nature of certain environments, thus closing off a critical eye to alternative voices. Navigating shifting political landscapes and tracking these dynamics at various scales might be a major challenge for those who study activism in today’s mainland China or in other highly and complexly politicized places.

SEAA editors Aaron Su ([email protected]) and Jieun Cho ([email protected]) edited this piece for the series, “Materialities and Movements in a Changing East Asia.” Please contact them with your comments and ideas.