Article begins

How Silicon Valley’s wealth produces uneven impacts throughout the region.

Silicon Valley is a geographic region, shorthand for all things tech, the global hub of the technology industry, and a synonym for places transforming through impositions of technocapitalism. In California, a confluence of Cold War defense spending, venture capital, support from Stanford University, and white flight from urban cores to the pastoral suburbs led to the establishment of a regional technology hub. The area has grown in wealth and power ever since. Today, in the wake of Tech Boom 2.0, Silicon Valley is the headquarters for some of the largest and richest companies in the world, including Apple, Facebook, Cisco, Intel, Hewlett-Packard, Oracle, Yahoo, and Alphabet, Google’s parent company. As technology companies outpace other industries, the economy of Silicon Valley is said to “defy gravity,” accumulating capital through both local and global endeavors. Yet, the astonishing accretion of wealth and power has also led to massive inequalities and displacements along historic racial and class lines.

We trace some of these uneven impacts in San Francisco and Oakland through maps and oral history created and curated by the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP). The project, a volunteer-led collective, was founded in 2013 amid frequent evictions, rapidly rising housing prices and rental rates, and the seemingly non-stop influx of disproportionately white and wealthy tech workers, tech capital, and tech companies to the San Francisco Bay Area. It now includes hundreds of maps and visualizations as well as oral histories, video pieces, reports, murals, and community events and has also expanded to Los Angeles and New York City.

Differential histories

AEMP works in multiple Bay Area spaces, and in doing so it is careful not to conflate differential histories of settler colonialism, racial dispossession, and uneven capital accumulation. While such histories predate the transformation of the region they also endure, informing current understandings of private and public space. In both Oakland and San Francisco, the impacts of what Cedric Robinson (1983) terms “racial capitalism”—the inherently racialized nature capitalism—cannot be chalked up to Silicon Valley alone.

Some brief history is useful here. Since colonists first landed on Ohlone shores, initiating cycles of racial dispossession, variegated cultural and geopolitical histories in the region have resulted in the smaller city of San Francisco accruing more wealth and more white residents than Oakland. Meanwhile, systems of carcerality, but also resistance, grew in Oakland, resulting in a historically racist police force, the generation of the Black Panther Party, and ongoing experiments in racialized repression (Self 2005). By the mid-twentieth century, San Francisco’s economies and white countercultures made the city more desirable than Oakland in Silicon Valley speculative calculi. Tech 2.0 has aggravated these histories, rearticulating racialized technopolitical violence and contexts of gentrification (see Maharawal 2017; McElroy 2018). Oakland is now being impacted by Silicon Valley as technocapitalism expands, yet we are wary of temporal imaginaries that position Oakland as San Francisco’s younger step-sibling, now prey to the same fate.

Tech bus evictions

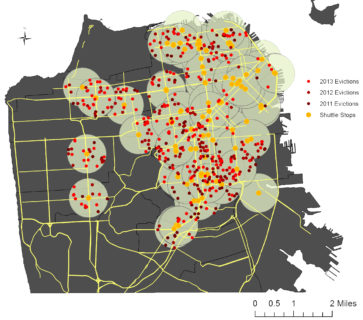

Figure 1: Evictions near shuttle stops in San Francisco, 2011–2013. Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, 2014

In 2013, at the height of the eviction crisis, AEMP cartographically correlated tech bus stops in San Francisco with no-fault evictions (when tenants are displaced for no fault of their own). Tech buses are luxury corporate shuttles that transport technology workers from numerous cities to and from their Silicon Valley workplaces. Our map (Figure 1) shows that 69 percent of no-fault evictions between 2011 and 2013 occurred within a four-block radius (green circles) of shuttle stops (yellow dots). Real estate speculators determined that areas surrounding the stops possess a heightened market value, as their proximity to the tech bus stops makes them attractive to Silicon Valley workers. More concretely, real estate agents and developers buy up these properties, speculating on the buildings worth once it is vacated of poor and low-income tenants. They then evict the tenants and either flip and sell the units as condos or re-rent them for more money. The AEMP made this map amid ongoing direct-action bus blockades that also brought attention to these connections between bus stops and displacement. It was used widely in protests against the tech shuttles and in hearings about their impacts at city hall.

Farewell, single room occupancy

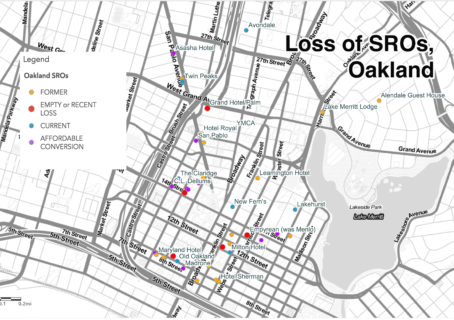

Figure 2: The loss of single-room occupancy hotels in Oakland. Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, 2018

This story-map (Figure 2) explores the loss of single-room occupancy hotels (SROs) in Oakland. SROs emerged during the late nineteenth century and became more popular in the mid-twentieth century as boarding houses for itinerant laborers and immigrant communities. Over time they began to shelter cities’ most precarious tenants. Between 1970 and 1990, over one million SRO units were destroyed nationwide, mostly so that real estate speculators could convert them into market-rate and luxury housing. In 2016, 18 SROs remained in Oakland, but one year later, as the city gained fame as the country’s “hottest” real estate market , the count was down to 5 (and 9 converted into affordable housing), with hundreds of rooms emptied or converted. The loss of SRO units in Oakland corresponds to an increase in houselessness (Figure 3), as many people evicted from SROs have no other viable housing options. As of 2018, Oakland’s houseless count was 2,761 individuals, a population which includes 300 youths and is estimated as 68 percent Black).

Figure 3: Increase in houselessness in Oakland. Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, 2018

In one widely reported recent example, an SRO called The Travelers was purchased by real estate entrepreneur Danny Haber and software engineer Alon Gutman. The two had already evicted tenants from San Francisco’s former Park Hotel, to then convert it into a dorm for tech workers or what one reporter called a “frat house for geeks after college.” Haber and Gotman were quick to follow suit in Oakland. After rooms were vacated, and with finances from First Foundation Bank and Crown Capital, the speculators “revitalized” The Travelers and advertisements soon popped up on Haber’s OWow platform for new “gorgeous apartments” with software engineer housemates.

Redlining

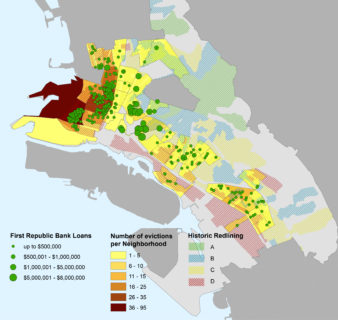

Figure 4: First Republic eviction financing correlated with a 1939 redlining map. Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, 2018

Recent real estate and development financing in Oakland, particularly that of serial evictors, reflects historic segregation in the city, exemplifying the ways in which current patterns of racial dispossession have historic precedents. Specifically, First Republic Bank has financed numerous serial evictors in Oakland over the last several years, making hundreds of loans to owners who have filed over 500 eviction petitions each (California Reinvestment Coalition and Anti-Eviction Mapping Project 2018). These loans correlate with 1939 redlining maps of the city (Figure 4), a racist cartographic devised by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in the 1930s, in which over a million homes across the United States were ascribed zones within “residential safety maps.” In these, areas were classified according to the age and type of buildings, but also the “threat of infiltration of foreign-born, negro, or lower grade population,” who were considered “dangerous” borrowers. Red areas were considered most dangerous, followed by yellow ones. The areas that serial evictors speculate on most today (financed by banks), are those red and yellow areas whose residents were denied financing in the 1930s, revealing what can be understood as racial capitalist revanchism. The immense wealth and influx of workers that characterize Tech Boom 2.0 exacerbates this process and its histories, which are integral to understanding the present.

Absentee home ownership

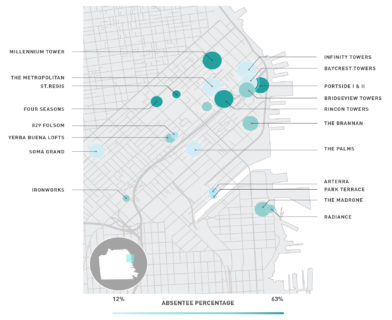

Figure 5: Percentage of absentee owners in luxury condo buildings. Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, 2018

Just as financing impacts the geographic contours of real estate speculation, it also affects development. Since 2014, a pro-growth development movement has gained power and influence in the Bay Area, particularly in San Francisco. Comprising several groups and largely funded by tech industry, the Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY) movement espouses neoliberal economics, alleging that the only way to solve San Francisco’s housing crisis is to develop more (mostly market-rate) housing. This “all housing matters” model claims luxury and market-rate development are as important as the construction of housing for poor and low-income tenants (McElroy and Szeto 2018). Yet, studies show that the city needs at least 60 percent of new development to be affordable to maintain the status quo and generally only 21 percent of its new homes are built as affordable units (Redmond 2017). Further, investigative research by Tim Redmond and Darwin BondGraham (visualized by AEMP, Figure 5) reveals that up to 40 percent of San Francisco’s new luxury development is in non-primary residences—second homes for absentee owners who live in wealthy Silicon Valley suburbs (McElroy and Szeto 2018). For reasons such as these, the housing justice movement has positioned itself against YIMBYism. Yet, the YIMBYs maintain a compelling discursive strategy by naming their opposition NIMBYs (Not in My Backyard), conflating those who oppose the development of market-rate condos in working-class neighborhoods today with the San Francisco NIMBY movement of the 1980s, in which white homeowners fought against poor and working-class people of color “invading their” spaces.

Narratives of displacement and resistance

Tenants’ passionate testimonies at City Hall hearings about housing policies, tech buses, and evictions, convey the affective dimensions of uneven and unequal development impacts. They can be read through street art and guerrilla tactics, such as spray-painted sidewalk stencils marking homes that no longer stand. And they can be heard in oral histories, in which people recount changing neighborhoods and lost apartments. AEMP’s Narratives of Displacement and Resistance Project records these stories, embedding them on an online interactive eviction map. By geospatially documenting personal tales of regional change and tactics of resistance, we merge maps such as those described above with more personal stories that never quite fit the script of normative map-making. In doing so, the project maps affects: the deeply personal and detailed experiences of living in and through the violence of gentrification. We conclude this piece with an excerpt from one of the people we’ve interviewed for the project. Cheryl lived in San Francisco for 30 years, mostly in her apartment in the Mission, before being evicted and relocating to Oakland. In this interview excerpt, she discusses the tribulations of seeking a new home and the loss of friendships and support networks she had built with her neighbors over the years.

God, it was painful. It was really painful. You know, I had my life at a certain level. I was able to cover my expenses. But I don’t live with a lot of cushion. Not too many things can go wrong before… I just don’t have a lot of extra resources. So it was really, really difficult and I don’t think they understood that. It’s not that easy to find a place that you can afford; it’s not that easy to find a place that you want to live. But even finding places that I wouldn’t want to live, I still couldn’t afford them. I had been there a long time and my rent was below what was out there on the market. And it was really, really hard. I looked at a lot of different stuff. I looked at some city programs that did subsidized housing things. It was tough. You know my circle kind of got wider and wider and I finally started looking in the East Bay. And I looked in Richmond it just was difficult. Really difficult. And kind of traumatic. I mean it’s not overdramatizing it because it is traumatic. It’s a lot to deal with when it’s not your choice to lose your home, to not have your neighbors that provide some little network and safety net for you. Just everything from, “Can you feed my cat while I’m gone?” to the night that the water came through the ceiling of the kitchen. You know, it was my neighbor who grabbed the flashlight and said, “What are we going to do?” and he got the people upstairs and we took care of each other. So it was traumatic in that way too.

Manissa Maharawal is assistant professor of anthropology at American University, Washington, DC. Her research looks at evictions, displacement, urban space, and urban activism. She has worked with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project since 2014 and cofounded the oral history wing of AEMP, the Narratives of Displacement and Resistance Project.

Erin McElroy is a doctoral candidate in feminist studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and cofounder of the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project as well as the Narratives of Displacement and Resistance Project. McElroy’s doctoral research focuses on technological entanglements between postsocialist Romania and post–Cold War Silicon Valley.

Cite as: Maharawal, Manissa, and Erin McElroy. 2018. “Mapping Dispossession, Mapping Affect.” Anthropology News website, November 9, 2018. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1038