Article begins

By conforming to norms of mask making, mask wearing, and regulating physical contact, people in India and the United States are redefining what is acceptable social conduct.

“Oh, I forgot to wear my mask!” How many times have we said this as we tried to leave our homes in this pandemic world, immediately rushing back inside to put on our cloth coverings, and wondering how long this will last? As inhabitants of the United States (New York City) and India (Nagaon, Assam) respectively, we realize that our forgetting has very little to do with memory. Rather, it is a struggle to cope with a new normalcy wherein we are learning to adapt to the new “mask culture.”

Two major parts of social life—interaction and public participation—have been challenged by mask culture. Although many argue that the practice of wearing masks is to show collective solidarity, it has also brought changes to our collective thinking. How is masking experienced in the United States and India? What kind of impact do masks have on social behavior and interaction? How do these interactions relate to prevailing social and cultural dynamics?

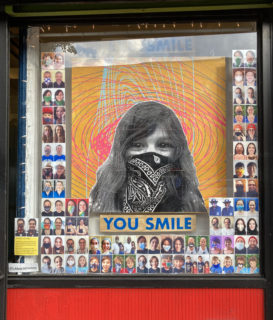

Image description: Window with a large greyscale image of a young person with long wavy hair wearing a mask surrounded by several smaller images of masked people. Beneath the image of the young person is text in blue that reads “You smile.”

Caption: “Eye Smile, You Smile,” art space window featuring photos of local residents. La Bodega Studios, Brooklyn, May 2020. Urmila Mohan

Masking protocols

In the last few months, individuals, families and communities in India have been negotiating a new social order. India’s roughly 1.3 billion people went under the first phase of lockdown for three weeks in March 2020. In April, Mumbai became the first city to declare face masks compulsory when it issued an order under the Epidemic Disease Act, 1987. Similar measures were followed by other Indian states with varying degrees of penalties. In Indian national politics and the media, there were prominent awareness campaigns on masking or covering one’s face. These platforms promoted the correct use of masks as markers of positive change in our habits and lifestyle. Through his popular Mann ki Baat radio series Prime Minister Modi repeatedly appealed to citizens to incorporate new habits and cultivate masking culture as a symbol of civilized society. However, from the very beginning, some in India have contested mask wearing as well as the mass lockdown and the crisis it created for various sections of society, especially the working class.

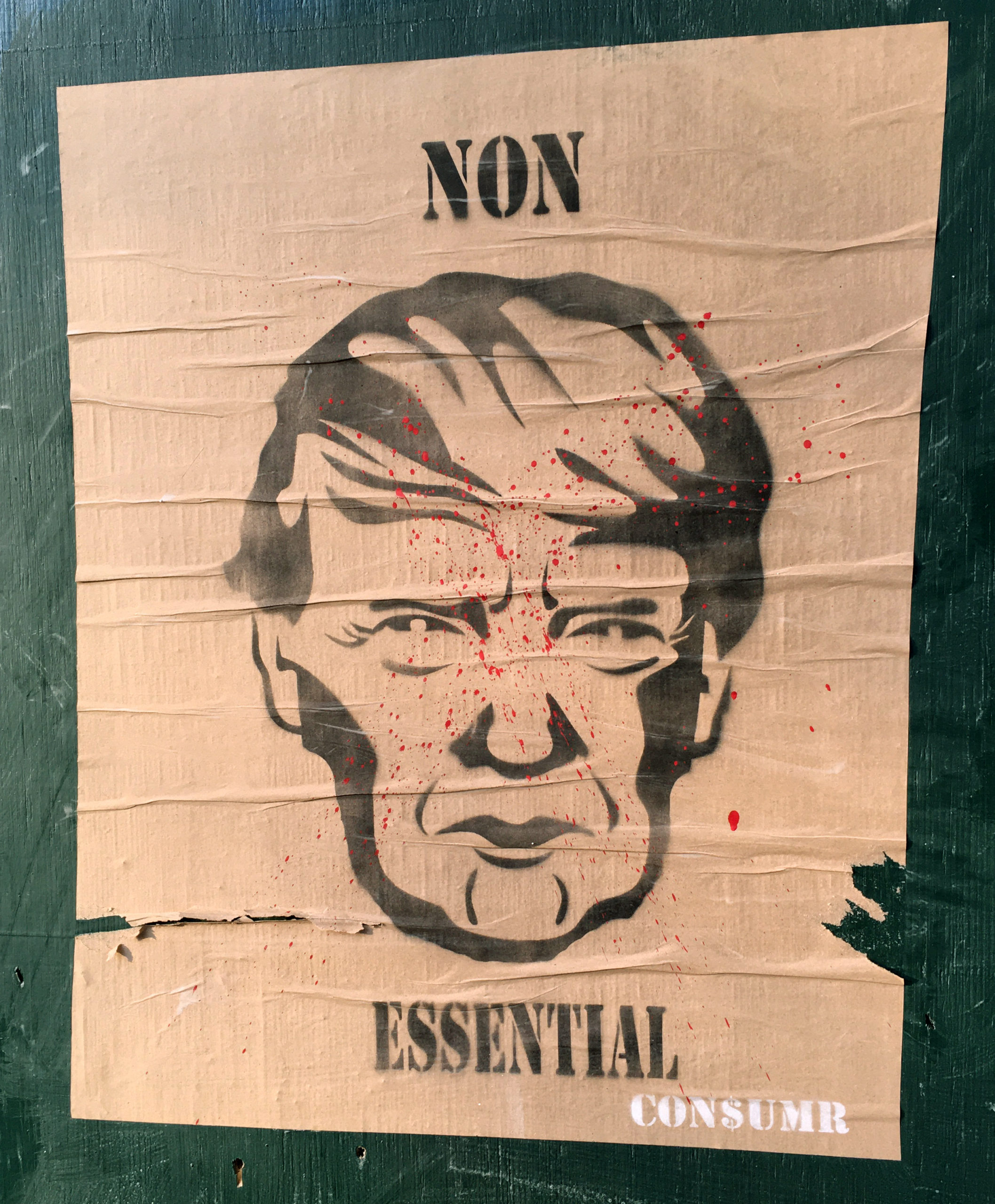

On June 5, 2020, long after masks were being worn in Asia as easy and inexpensive preventive measures, the World Health Organization issued its endorsement of masks. Despite recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and federal agencies, masking has been variable in the United States and its population of 331 million. An executive order on April 17, 2020, made face coverings mandatory in New York State but enforcement has differed even within New York City—a trend repeated in other parts of the United States where mask culture differs by state, county, and city. When New York City was experiencing the first wave of the pandemic, sentiments of anger and frustration were reflected in posters (see for example, figure 1). While this image does not address President Trump’s resistance to masking, it implicates him in broader pandemic “culture wars.” The use of the term “nonessential” refers to how jobs and people were demarcated. It invokes the social fault lines exposed by a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) for essential workers.

Image description: A tan poster is pasted to a green surface. In black paint, the poster depicts a face that resembles Donald Trump and text stating non-essential. Red flecks of paint create a faint x crossing out the face.

Caption: “Non-essential,” stenciled poster of an unmasked President Trump on the wall of a construction site. Brooklyn, April 2020. Urmila Mohan

Masks and embodied socialities

According to Erving Goffman (1967), our social life is meaningless and unpredictable without rituals of “face-work” that involve being close to or interacting with others. Verbal and nonverbal acts mediate interactions between people.

The pandemic has prompted us to re-evaluate some of the categories, distance, and intimacy, used when exploring human interactions. The new mask culture has meant that everyday rituals and cultural greetings such as standing close to show trust, shaking hands to signal an arrival or departure, and hugging and kissing as a means of displaying affection, are replaced with new ones. As our personal space has shrunk, walking around parts of Brooklyn and Nagaon has given us an appreciation of the new interactions being formed. In the small town of Nagaon, people are used to visiting neighbors and sharing things. Now, they must find new ways to negotiate social distance, for instance, by staying apart while conversing. Similarly, new gestures are enacted in Brooklyn when giving a mask to another person becomes a way to show concern. In another example, the window of an art space, appropriately titled “Eye Smile, You Smile” helps us connect by depicting the power of smiling “with the eyes.”

Image description: One person wears a mask and stands in front of a blue gate, hands on his hips. Another person stands on the opposite side of the gate and clasps the bars. They converse through the gate with a few feet of distance between them. A paved road and greenery are visible in the background.

Caption: Simashree Bora’s mother and uncle conversing through a gate. Nagaon, June 2020. Simashree Bora

The making of PPE also reveals new interactions. For instance, Ethan Dean, an undergraduate student who lives in California, made 500 masks to help his mother, the chief financial officer of a beverage distribution company, protect her several hundred employees as they helped restock shelves. In another example, Cheri Vasek, a retired Associate Professor of Costume Design and Technology, University of Hawai’i, Manoa, transferred her skills to a community project called “Operation Protective Gowns” in Santa Fe, New Mexico to help make over 1,000 gowns for healthcare workers at local hospitals. While making PPE, producers also have to factor in the protective functionality of the garment, size variation, and the feel of the fabric against the skin.

In India, people started wearing masks made from the same ordinary fabrics they use for clothing in their everyday lives. The Times Group, India’s largest media conglomerate, launched a nationwide campaign called “Make Your Own Mask,” widely popularized as #MaskIndia, that aimed at promoting homemade masks and their correct wearing. At the same time, there was an upsurge of regional masks that promoted Indian traditions through their weaves and patterns along with enabling small-scale economic growth by employing youth and women. By endorsing such steps, the Indian government draws upon tropes of “self-reliance” (atmanirbhar) to boost the new economy.

Image description: An overlapping collection of masks made of traditional weaves, motifs, and designs that are popularly used in India.

Caption: Masks enhanced with traditional weaves, motifs and designs. Nagaon, June 2020. Simashree Bora

In addition, it quickly became evident that, within domestic settings, it was mostly women who were making masks for their families, the local community, and the immediate neighborhood, and that this had become a source of income for families where other types of work were scarce or nonexistent. Reena Das and Radha Das (names changed) formerly worked as domestic helpers. With the national lockdown, however, their income stopped. For the last three months, they have been making masks. They each make 20–25 masks in a day for which they earn 10 rupees (13 cents) per item. The masks are then sold to local entrepreneurs.

Far from being only limited to medical use, masks have gained aesthetic value and one can purchase them in nearly any style. Locally produced masks in India, carrying traditional and ethnic elements, can be purchased in stores or online as “culture masks.” In the United States, varieties of masks are sold by both major clothing brands and small businesses. In both countries, masks have become fashion items available in expensive materials, signalling that face coverings have transitioned from the realm of the everyday to the ceremonial.

Image description: An Indian couple standing next to each other and wearing masks made from traditional silk of Assam on their wedding day.

Caption: A couple wearing masks made from traditional silk of Assam on their wedding day. Limpy Khataniar

Our initial comparison indicates that mask cultures vary, for instance, through phenomena of resistance. In the United States, the protests against masking involve emotions over variable guidelines and ideas of personal freedom as well as the unique politics of states within a federation. In the Republic of India, protests have a common root in channeling the frustration over the economic effects of a long drawn out lockdown instituted by the central government.

Another point of difference is the context in which masks are made for local communities. Mask making in the United States could be seen as a form of citizen activism in response to the lack of PPE, while in India the activity is primarily one of income generation although attempts at creating solidarity cannot be discounted. Further in the Indian context, masks have also become markers of regional identity.

By conforming to norms of mask making, mask wearing, and regulating physical contact, people in India and the United States are redefining what is acceptable social conduct as well as what actions are to be associated with states of care and connectivity. As the effects of the virus extend over the foreseeable future, masks are not simply a response to the crises but are actively shaping our pandemic world.

Urmila Mohan is an anthropologist and editor of The Jugaad Project ([email protected]).

Simashree Bora is an assistant professor at the Department of Sociology, Cotton University, Assam, India ([email protected]).

Please send your comments and ideas for SHA section news columns to contributing editor Rose Wellman ([email protected]).

Cite as: Mohan Urmila, and Simashree Bora. 2020. “’Mask Cultures’ in the United States and India.” Anthropology News website, September 25, 2020. DOI: 10.14506/AN.1506