Article begins

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread through communities in 2020, museums turned their attention to the project of curating collections to illustrate material cultural responses to the virus and daily life under lockdown.

Anthropologists and collections staff at the Field Museum in Chicago gathered—remotely—to discuss the museum’s role in assembling such materials. Since then our team has been collecting materials, interviewing makers, and puzzling through the questions: With whom will we do this work? How do we document a pandemic during a pandemic? What sort of things will we include in this archive that is both for the present and for the future?

Pandemic Collection relations

With whom?

We decided to begin where we are, with the relationships we have already established; since the 1990s, the museum has been working with community partners in Chicago, Native North America, northwest Amazon, and the Philippines. We were able to draw on these existing collaborations and snowball from them to enlarge our participant sample.

How to collect?

Given that we began this work at the height of pandemic precautions, when both travel and in-person meetings were not possible, we have relied on technologies such as remote interview platforms (Zoom, Google Meet) and social media platforms (WhatsApp). We aimed to be especially respectful of people’s time and senses of well-being noting that pandemic burdens and those of intersecting climate and economic crises were unevenly distributed among participants. Yet we also found that many of the people we interviewed welcomed the opportunity to share their experiences, particularly with the early months of pandemic restrictions. We also conducted a government documents review and attended relevant webinars. And with the availability of vaccines, we have been able to conduct in-person interviews with some our contributors.

And, what to collect?

Masks? Yes, we have collected a number of handmade pandemic-related face coverings and mask memes. In the Philippines, for example, Analyn Salvador-Amores worked with community partners to collect masks made from textiles that have protective symbols woven into them. And Native North American fashion designers Loren and Valentina Aragon’s masks intentionally feature symbols from Pueblo ceramics in repurposed Navajo fabrics.

While masks were an obvious focal point, our relationships with our contributors helped to determine what would become part of the collection. The collection incorporates a range of materials from the stuff of everyday life, like matico, a plant grown and used by many Shipibo in northwest Amazon to treat illness and wounds and on which people relied when they encountered difficulty in accessing medical care. Other items include a dollar bill with the words “C-19 is a hoax” written on it and given as change at a Chicago area gas station, daily journal entries, original artwork, poetry, and song.

From the outset, our team was clear that the museum’s collection would need to include responses to the virus raging through our communities as well as interpretations of racism and social inequality that continue to shape health outcomes and material well-being in places the museum conducts research. This broader conceptualization of the pandemic environment arose from discussions among museum staff and research partners, and is shaped by ongoing calls from within anthropology to approach research through anti-racist methodologies such as Aisha Beliso-De Jesús and Jemima Pierre’s recent call for anthropologists to attend to the continued resonance of “‘folk’ concept[s] of race” and to processes of racialization involved in establishing systems of material inequality across the world. We take inspiration as well from critical native studies scholarship documenting the many strategies Indigenous peoples have developed to endure centuries of sustained settler state violence, especially by centering creative endeavors in “survivance” strategies (Vizenor 2008).

As of June 2020, our collection consists of more than 60 interviews, 187 objects including digital artifacts, and hundreds of ethnographic materials.

Pandemic Collection snapshots

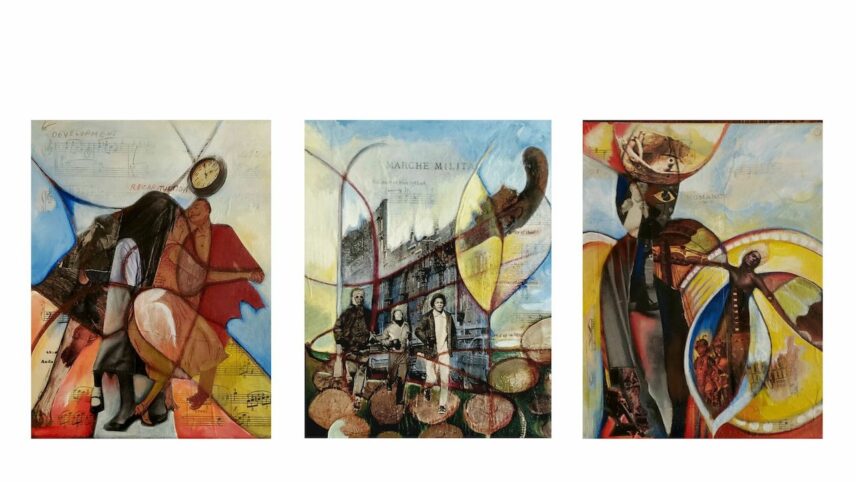

In March 2020, Beth Herman Adler converted what would have been her gardening journal to an archive of her daily reflections on the first 30 days of COVID-19-related shutdown in the United States. The converted handmade journal is a mixed media collage work in which Adler used a paint pen to write out questions such as “Do the plant and animals wonder what’s going on?” and thoughts about the virus, “Getting bigger, getting closer.” That same month, Makeba Kedem Dubose set to work on a mixed-media triptych entitled “Tangled Mass” engaging the aftermath of chattel slavery in US society. She began the piece after Breonna Taylor was killed by Kentucky police in her home on the eve of the shutdown: March 13, 2020. “Tangled Mass” grapples with themes of suffering, protest, resistance, resilience, and time with images of generations, genders, stone, sky, plants, butterfly, animals, and more.

Several months later, in June, Nick Garcia received a series of texts about confrontations between police and social justice protestors from his brother, who was working security for the Merchandise Mart in downtown Chicago. Garcia turned the texts into a hip-hop song coproduced with North Carolina artist DJ DOUG. Also at those Chicago protests, local photographer and artist Isiah ThoughtPoet Veney captured a powerful set of images chronicling Chicagoans’ efforts to occupy the streets in protest against state violence.

In July, Sarah Hinojosa printed poems and used her grandchildren’s colored pencils to embellish the paper, which she then slipped inside plastic sleeves and tied to a tree trunk outside her home in an effort to communicate with a neighbor child she saw walking regularly on her street. She called it her “poetree.” Thousands of miles south of Chicago, in Bogota, Claudia Mejia Eimenekene worked with the Cabildo Indigena Monifue Urukɨ, an Indigenous rights organization, to organize shelter, care, and food provisions for Indigenous urban residents who drew on cultural traditions to help community members cope with loss of income and problems with access to medical treatments. Uruki’s community established a maloca, a ceremonial roundhouse, with Uitito people living in a settlement on the outskirts of Bogota to provide a space of care and mutual aid offering essential and preferred foods including manioc, fish, chilis, and hot chocolate during a time when many families were cut off from familiar food distribution channels.

Grief and repair

Museum spaces and processes may serve as resources for collective grieving and help communities approach repair in the aftermath of profound harm. In a recent issue of Museum Anthropology, Sabra Thorner considers her ongoing collaboration with Koorie artist and curator Maree Clarke whose methodology combines traditional and digital technologies to create materials that are housed now at a number of museums in Australia, writing, “[T]he museum, in this sense, is a field of relations more than it is a structure or an enduring institution.” What “field of relations” and associated qualities of place making will the Field Museum foster during this time? At present, we remain in the throes of an evolving pandemic, entering what science journalist Ed Yong is calling the “Pandemicene” with a majority of the world not immunized, more than one million COVID-related deaths in the United States, and six million deaths worldwide (vastly undercounted). We have no national memorial and no events dedicated to national grieving in the United States. The Field Museum Pandemic Collection team is seeking to support partner-led initiatives designed to collectively mourn and hold space for repair, one example of which is Jenny Kendler’s “Mending Wall,” adjacent to the museum grounds. The Pandemic Collection aims to both serve as a material culture expression of this historical moment for future generations while also facilitating exchange and collective actions among our contributors.