Article begins

The 2014 film, Monuments Men, took to the public an ongoing academic and political dialogue about the protection and restitution of cultural property in Europe.

Last fall, I spent part of my sabbatical at the Rathgen Research Laboratory in Berlin, run by Stefan Simon, whom I can only describe as the George Clooney character in Monuments Men, given his heartfelt commitment and efforts to protect cultural properties. Since he is also former director of Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH), I embarked on a conversation with him to learn the difference between “restitution” and “repatriation.”

Image description: A photograph of a tan building with multiple stories. The middle section is slightly taller than the right and left sections with one more floor.

Caption: In 1888, the Rathgen Forschungslabor became the first laboratory in the world, dedicated to the conservation of museum objects. Sandra L. López Varela

Repatriation, to me, is part of a dialogue taking place in countries which were part of the British Empire or are members of the British Commonwealth. Most of these nations have been concerned about returning human remains and owned objects to Native Americans, First Nations, and Aboriginal groups. In the United States, for example, the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), promised artifacts would be repatriated to the rightful owners in less than a decade after its approval. I am not well versed to discuss why this is still an ongoing process. I wonder, however, if part of the problem is a concern with the question of who owns the past—always determined by experts or institutions. In my opinion, this has set up a trap for those nations constantly struggling to reclaim property of looted or stolen artifacts, lately purposefully sold at major auction houses in Paris. Most of these auction houses have relied on the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property to determine if cultural properties were legally obtained and exported from a particular country. Simon pointed out that terminology shouldn’t be the center of my concerns. Instead, I should be concerned about stakeholders discussing what is contested among them, under principles of equality.

In 2010, Simon helped the German government during the confiscation of Leonardo Patterson’s antiquities collection at Munich airport. Despite the collection containing pieces from Latin American countries, mainly from Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, and Peru, the Mexican government was the only nation with the means to travel to Germany and to assess the collection. No scientific instrumentation was used in the process; a qualitative assessment was made by Mexican experts. Historically, Mexico’s stewards have claimed that the “quetzal feathered headdress” or “cape” housed at the Weltmuseum in Vienna belongs to the Aztec ruler Montezuma. However, the Guatemalan government has never claimed its property, even if it is made of quetzal feathers. Therefore, Mexicans can enter the Weltmuseum for free with proof of nationality.

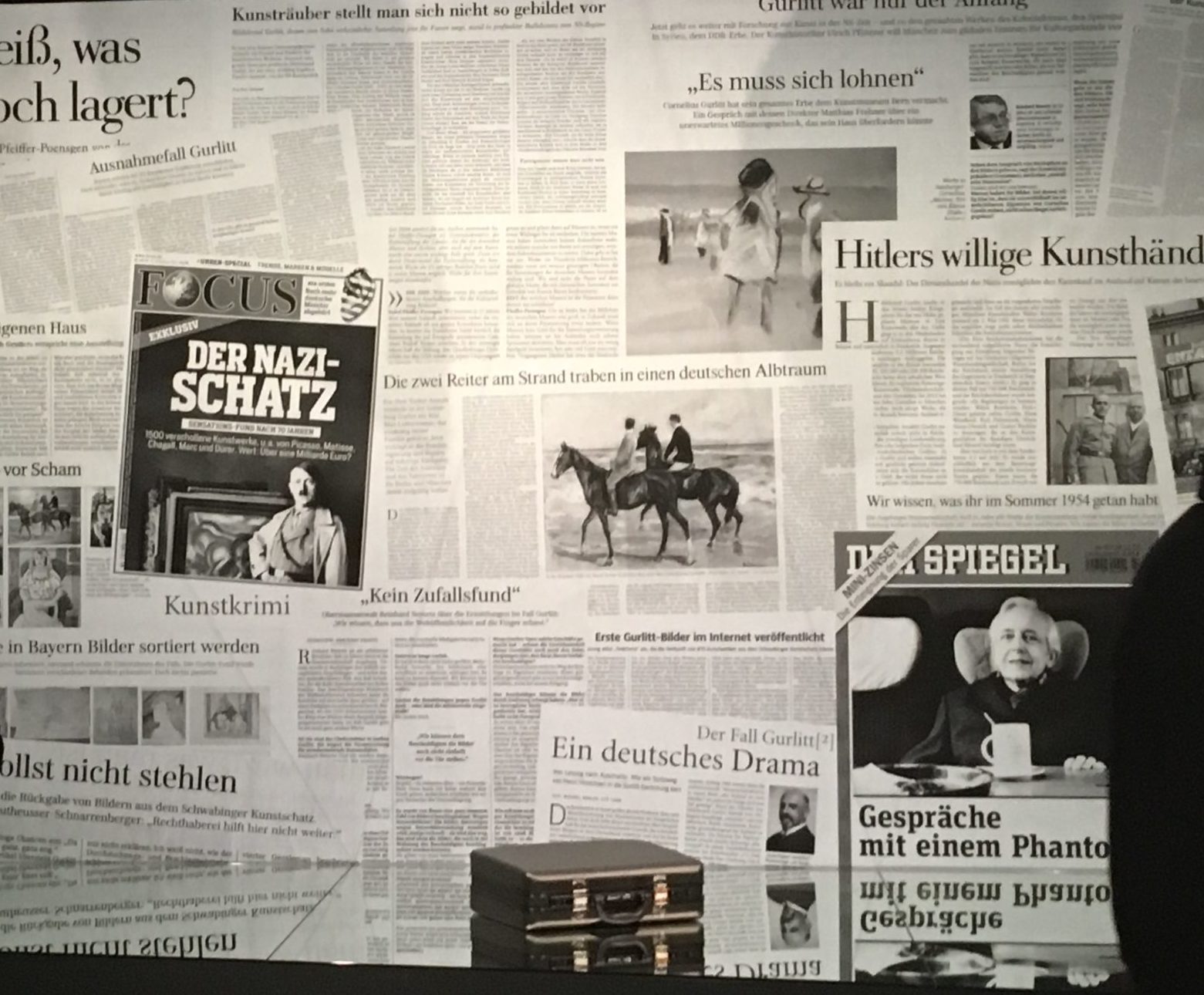

Repatriation takes a different route in Germany, one that is embedded in legal authority and responsibility to its past. Restitution of cultural property is the term used by experts to refer to looted art or displaced cultural assets displaced from or to Germany during or immediately after the Second World War, by either German or Soviet troops. The German government has diligently worked to return Nazi-confiscated art to the rightful owner, most recently in the well-advertised Gurlitt case. Austria is seemingly further ahead than Germany in its commitment to restitution. Still, the German government has created a Lost Art Database, archiving cultural objects that were relocated or seized during persecution under the Nazi dictatorship and the Second World War, and which is administered by the Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste at Magdeburg. Obviously, the discussion on holocaust art has gained more ground than the discussion about cultural heritage from other colonial and postcolonial contexts in which Germany was involved, even in the history of East Germany. The legal framework considers cultural assets, which are part of a nation’s history and identity, must not be taken hostage in war or serve as restitution in kind. Since 2016, importing cultural property to Germany requires an export permit proving that the objects have been legally exported from the country of origin, according to the Cultural Property Protection Act (Kulturgutschutzgesetz). This framework has already prevented the selling of artifacts from Guatemala, which had been put up for auction in Berlin.

Image description: A photograph of a wall with black and white cutouts of German newspapers and magazines reporting the confiscation of masterpieces stolen during the Nazi regime. In the foreground, a black briefcase can be seen.

Caption: More than 200 confiscated masterpieces from the Gurlitt Collection were on display at the Gropius Bau Museum in Berlin in 2018. Sandra L. López Varela

During our conversation, I asked Simon if museums are ready to give away their most visited precious objets d’art, such as the bust of Nefertiti or the Elgin Marbles. Museums frequently abuse the discipline of conservation by using it as an “escape” to avoid their responsibility of returning an object back to a nation. Museums have tended to claim that transportation could impact an object’s state of conservation or that the reclaiming nation does not have enough means to properly secure and maintain the asset. Simon reminded me that in 2017, President Emmanuel Macron commissioned Felwine Sarr and Benedicte Savoy to write a proposal to restitute 80,000 objects taken from sub-Saharan Africa, most housed at the Musée du quai Branly–Jacques Chirac in Paris. The report questioned the legitimacy of the West’s retention of objects with troubling provenance. It not only put on the spot the opening of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, which will house collections of artifacts of dubious provenance from all over the world, it gave the impression that in facing their colonial responsibility European nations would have to empty their national museums. At that moment, restitution became a public relations issue for Germany and France. Cultural authorities in Germany opted to sign an eight-page agreement to work with museums and to make sure that wrongfully obtained artifacts are given back to their rightful owners, to produce inventories and to make them publicly available to facilitate any claims. The French government faced public outrage, as restitution was widely understood as a policy to empty national museums of African objects. A proposed solution of loaning these objects to the African continent infuriated the Nigerian government. More than a year later, the report lost momentum and not a single object housed at a French museum has been returned to an African nation.

Building partnerships will only translate into a win-win situation if we understand knowledge trumps possession.

Full or partial restitution is probably not the answer to overcoming the obsession with the possession of artifacts. Questions raised by the policy of restitution are an invitation to reassess the role of museums, curators, and professionals within a system of appropriation, or rather possession and disaffection, which has failed to communicate the moral, historical, and scientific implications of separating an item from its historical context. Some museums seem to be more interested in possessing objects than in creating knowledge out of their collections. Museums are places where an item’s rich history can become a meaningless object of digital and analogue collections, a container from a certain time period and region.

Museums continue to keep their interest in owning objects or preparing blockbuster exhibitions, but what about the knowledge these provide? Museums are highly trusted institutions. If they are not telling the public where objects come from, museums are not only betraying the public, they put themselves at risk of losing their main asset: public trust. Museums have to move beyond a dialogue of ownership and instead engage in significant partnerships with these nations. For example, Yale University returned the objects collected by Hiram Bingham, which ended up at the Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco (UNSAAC). In addition, a co-signed agreement established the UNSAAC-Yale International Center for the Study of Machu Picchu and Inca Culture in Cusco. I recommend paying a visit to the wonderfully curated small museum called Casa Concha on the way to Machu Picchu. Yet these efforts do not entirely compensate the alleged “loss” of Peruvian objects and are not enough to curb the global plague of illicit trafficking.

Is this the solution?, I asked. For similar partnerships to work, Simon responded, these have to be turned into a unique opportunity to work together and to learn about how an object was made, what was it made for, why is it meaningful, what was inside the object, how was it discovered, and how it is studied. Do you think the German government will engage soon in similar actions? Let’s hope it does. It is an addition to Germany’s internationalization strategy, an understanding that solutions can only emerge through transborder cooperation in education, science, and research. Unfortunately, no solution is perfect. Building partnerships will only translate into a win-win situation if we understand knowledge trumps possession.

Sandra L. López Varela is contributing editor for the Archaeology Division’s section news column.

Cite as: López Varela, Sandra L. 2020. “Museums and the Restitution of Cultural Property.” Anthropology News website, April 28, 2020. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1395