Article begins

Robert Samet: Sonorous Worlds is a conceptually rich account of young musicians coming of age in El Sistema, Venezuela’s renowned program of classical music education. Could you begin by telling me a little bit about El Sistema?

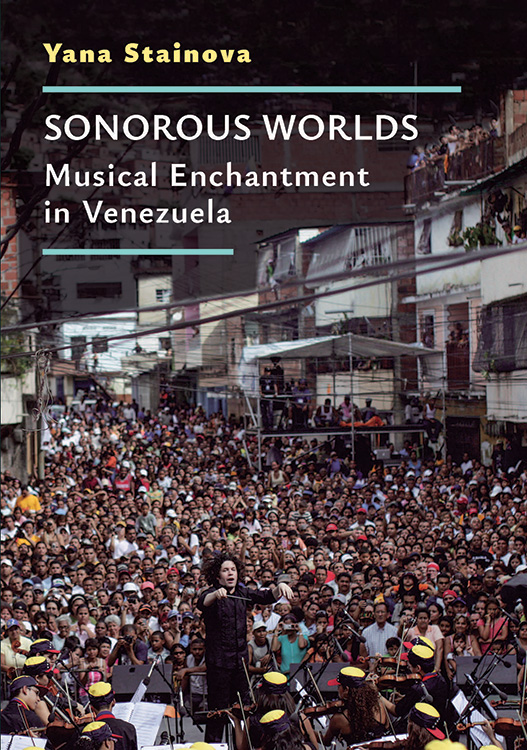

Yana Stainova: El Sistema is a Venezuelan initiative that brings free classical music education and instruments to young people all over the country. It was founded in 1975 by economist and musician José Antonio Abreu and has grown over the years to include more than a million members.

El Sistema aims to challenge the elitist status of classical music by making it widely available, mostly to those living on the margins of society. This is especially important in Venezuela, a country fragmented by socioeconomic inequality, ethno-racial discrimination, and everyday gang violence. El Sistema promotes a method of collective practice, teaching, and performance of music, a contrast to individualist models prominent in the Global North.

RS: One of the things that I like most about Sonorous Worlds is how you have tethered it, ethnographically and experientially, to the wonder of music. What led you to El Sistema? How did your own musical training—you’ve been playing since you were six—inform the ethnography?

YS: The roots of my interest in Venezuela’s El Sistema lie in my first encounter with Latin America during a study abroad semester in Chile. I wrote a senior thesis in Spanish on the place of poetry in the Chilean transition from dictatorship to democracy and studied the work of six contemporary poets. This research sparked my interest at the intersection of artistic practice and political struggles in Latin America.

In the first year of my PhD, I watched a documentary about El Sistema (Tocar y Luchar) and I was smitten. The images of children playing music in the barrios and hearing them speak of how attached they were to their instruments resonated with my own childhood of playing piano and flute. I felt certain that I wanted to do research on El Sistema for my PhD and within a few months, I was on a plane to Venezuela (a country I had never visited before) to see this phenomenon for myself. Playing music together with my interlocutors was crucial in approaching an experience that many of them described as being beyond words.

RS: When you started fieldwork in Venezuela, El Sistema was embedded in a context of acute political polarization. How did that impact the research?

YS: This was one of the greatest challenges for me as a researcher. As soon as I set foot in Venezuela, I realized that one of the first things people wanted to find out about one another was whether they supported Chávez or the opposition. I have learned about the complexities of polarization from your own work, Robert, and I remember it being a topic of conversation when we first met in the early days of my research in Caracas. I felt torn in positioning myself in this political landscape. As the offspring of the revolution that brought about the fall of communism in Bulgaria, I was skeptical of the socialist project. At the same time, my experience in Chile had made me wary of the Latin American right.

Within music practice at El Sistema, people frequently sought out a respite from the vocabulary, if not the inescapable reality, of political polarization. Through collective music practice, they aspired to build communities across political divides. While these communities were not always solid or long-lasting structures, but frequently ephemeral and ineffable like music, they nevertheless provided the experience and possibility of another form of relationality.

RS: Throughout Sonorous Worlds, you describe the fraught social, economic, and institutional conditions under which these young musicians labored. You do so with tremendous empathy, but you also refuse to frame the book as the kind of critique to which many of us have become accustomed. Even though El Sistema has serious flaws, exposing them is not the book’s central concern. Instead, you’ve oriented the ethnography to follow the aspirational thread of musical enchantment. Why did you decide to emphasize enchantment?

YS: Even though I felt pressure to do so from mentors, I realized that writing a book emphasizing critique of the institution would be untruthful to the overwhelming excitement my interlocutors experienced when playing music. “Me encanta,”they would say about music, meaning that they are enchanted by it, that they love it. To be enchanted is to feel wonder and fascination, to take pleasure in an activity. To insist on critique, even though I was witnessing enchantment, would be condescending towards my interlocutors, as if I knew more about their reality than they did or I had more acute powers of observation, something I refused to do. Instead, I aspired to make my interlocutors the theorists of their own situation and I put myself in the place of learning from them, allowing myself to be enchanted with and by them—to be changed. This does not come at the expense of being cognizant of the repressive power structures that are pervasive in El Sistema as an institution with hierarchical leadership. I expose the impact of institutional and state power on music playing and study its intersection with enchantment.

RS: Near the middle of the book, you defend your concept of enchantment against critiques that it is depoliticizing. What are the strengths of enchantment as methodology? Does it have any limitations?

YS: Frequently in social science scholarship, we focus on the structural forces pressing down on our interlocutors, to the point that we risk portraying their lives exclusively in the vocabulary of violence. My interlocutors, in contrast, painted their lives in the words of music and enchantment, and expressed brave dreams about the future. I chose enchantment as a conceptual orientation that privileges the fragile life projects and aspirations of people who have entire systems stacked against them. A method of enchantment emerged as a political choice of being complicit with such world-building forces in my field site.

The limits of this method lie where violence becomes too unbearable to allow any space for enchantment. After the publication of my book, musicians who stayed in Venezuela have shared with me that the economic crisis in the country is making it hard to afford food to eat. Another person shared her testimony of sexual abuse, a systemic problem within the institution. The deep sadness and violence of these stories delineated the limits of enchantment. I write about this in a book chapter, “In the Wake of Disenchantment: Silence and the Limits of Ethnographic Attentiveness.”

RS: My favorite paragraph from Sonorous Worlds is your response to your former Bulgarian philosophy teacher who lamented that El Sistema was too good to last. Rather than succumbing to fatalism, you respond by shifting emphasis. You write: “a focus on the flourishing of individual lives can help us theorize the failure of political systems.” How did the experience of growing up in postsocialist Bulgaria equip you to think about Venezuela? Did Venezuela make you think differently about Bulgaria?

YS: Thank you for this question! I grew up in Bulgaria in the aftermath of the peaceful revolutions that brought about the fall of communism in 1989, a time of great hope but also of economic suffering. I remember electricity and food shortages, empty shelves in the stores, an inflation that devoured my mother’s salary in a matter of hours. When, years later, shortages and inflation hit Venezuela, I felt that my life experience brought me closer to the precariousness my interlocutors were experiencing. I also grew up hearing my mother’s friends tell stories about the violation of freedoms during communism and their inconsolable dismissal of Bulgaria’s communist past.

My upbringing armed me with a skepticism of the socialist project in Venezuela. When I encountered interlocutors who supported Chávez, however, I lingered in our differences, rather than try to resolve them. Holding on to what we held in common—a love of music—usually lessened the intensity of these differences. I felt compelled to write about the individual and collective flourishing that emerged in the rubble of the collapse of the Venezuelan political system. This taught me to look past my community’s complete disillusionment with Bulgaria’s communist history to discern, between the cracks, practices and traditions of value originating in the past that survived the system’s collapse. This includes a disciplined and systematic tradition of education in the arts, music, and beyond, that are still an integral part of who I am.

RS: Writing, like music, is a craft, and this is a beautifully crafted book. I wonder if you could reflect, for a moment, on narrative enchantment? How do you think about the encounter between writer and reader? What kind of reading experience were you aiming for?

YS: I wish I could say I was able to strategically predict the reading experience. However, I think I just wrote the book I was able to, while trying not to limit my audience to the scholarly community. Yesterday, at a party, someone asked me whether it was hard to write a book. My instinctive response was to say that no, it was not. I reminisced later about why I had responded like that, knowing full well how much effort it took to write the book. I think my answer reflected the deep love for the subject and the urgent need to communicate as accurately as possible my own and my interlocutors’ experiences in the field. Giving free reign to this love and urgency made me more of a medium, rather than a calculating agent, of the writing process.