Article begins

No one was sure what form carnival would take in New Orleans in 2021. Mardi Gras 2020 had proven to be a COVID-19 super-spreader event, and many of the social clubs called “krewes” that organize carnival parades and parties canceled their plans, anticipating that public gatherings would still be forbidden. The day the mayor officially banned parades, November 17, 2020, someone made a joke on Twitter: “It’s decided. We’re doing this. Turn your house into a float and throw all the beads from your attic at your neighbors walking by. #mardigras2021.”

The tweet went viral, and the tweeter, Megan Boudreaux, who usually parades in the sci-fi-themed Intergalactic Krewe of Chewbacchus, suddenly found herself at the helm of the new Krewe of House Floats. Various ideas for alternative, safely distanced carnival celebrations had been floated, but this one really captured New Orleanians’ imaginations. House floats were a pragmatic, inventive play on the form of carnival, and the perfect outlet for the creative energy that people usually put into making the material culture of carnival.

By Mardi Gras day, three months later, over 3,000 house floats had popped up around the city. I watched them blossom from a distance as COVID-19 regulations kept me at home in Nova Scotia. I scoured social media and news media, Zoomed with research participants, and followed photographers―including Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee, who I had worked with already―to find out how people were playing with carnival to create this novel form of public culture.

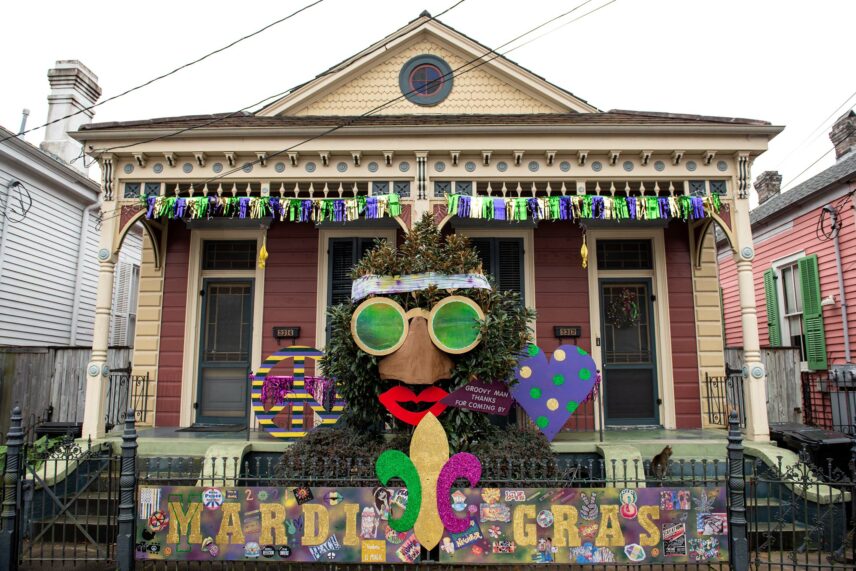

Play is always embedded in its social context, so just like carnival in non-pandemic times, house floats reflected uneven access to materials, labor, and know-how. Wealthier people could afford to pay artists or rent props from professional float-building companies to create their house floats. Caroline Thomas, a float designer, and Devin DeWulf, captain of the Krewe of Red Beans, launched the ingenious “Hire a Mardi Gras Artist” initiative, which crowdfunded employment for float builders and raffled off a house float each time the fund reached $15,000. In this way, people with less money had a chance of winning a top-quality transformation of their home, while laid-off artists had work for the season. Many more house floats, though, were created by their households along with friends and family, with whatever materials they had to hand. Residents of a “double shotgun” house (two narrow houses sharing a central wall and front porch) trimmed a shrub into a hippie figure in a tie-dyed headband for their “Peace, Love, and Mardi Gras” float, demonstrating how well traditional New Orleans architecture suited the house float form.

House floats featured less political satire than many carnival parades, perhaps because makers had to live with their float for weeks instead of hours. Some gently poked fun at the pandemic or at carnival itself, like the green, gold, and purple parody of a parade at a suburban home, complete with porta-potty. Some were simply whimsical. Many paid tribute to beloved local cultural icons, including jazz, oysters, the late chef Leah Chase, or the late musician Dr. John. House floats were typically funny, sweet, and sincere, showcasing what New Orleanians loved and missed about their city as COVID-19 quieted carnival.

House floats also resituated carnival in neighborhood space and sociality, temporarily reversing the centralization that City Hall has increasingly imposed on carnival parades. Neighborhood subkrewes branched off within the Krewe of House Floats, organized via Facebook groups. The St. Roch neighborhood chose as their theme “St. Roch and Roll,” which suited the Société des Champs Elysée, a small carnival krewe whose theme for 2021 was already “We are the Champions.” Their house float, designed by artist Miz Marrus and built at their captain David Roe’s home on Elysian Fields Avenue, became a spot to stop for a drink and distanced socializing some nights. Symbolically, house floats echoed the open house parties that many New Orleanians host during carnival season, especially if they live near parade routes. In 2021, the invitations were not to come play at particular homes but at homes in general—at a safe distance.

Carnival season in New Orleans is always a playful time. People play with words as they come up with themes for parades, floats, and costumes. They play with materials and crafting skills as they make these things. They play with personae and hedonic pleasures as they participate in the parades and parties that culminate in Mardi Gras day. Because carnival is remade every year, by people responding to the materials and events around them, improvisation and resourcefulness are built into its social structure. This, I think, is what enabled the playful reconfiguration of carnival as “Yardi Gras” in 2021.

No one was sure whether house floats would feature in carnival 2022. Ultimately, few were built, as people returned to the familiar rhythms of mobile parades. The traces of house floats still glow in people’s memories and in the remarkable collective documentation of this play on carnival for pandemic times.

Photos by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee, text by Martha Radice