Article begins

Community engagement and participation in heritage have become buzzwords for heritage scholarship.

Both community engagement and participating in heritage have promised not only a path out of unethical research practices, but also a route toward empowerment and liberation: to reclaim the past and mobilize heritage for the benefit of local and descendant communities, preventing the continuation of extractive colonialist research practices. Calls to ethical, engaged heritage and archaeology suggest that multivocality is key to any project—that a singular narrative of history is to be avoided in favor of an emphasis on the diversity of the past and present, and the opportunity for multiple groups to participate in and assert ownership of heritage (e.g., Habu et al. 2008).

This emphasis on ethical engagement is a welcome counterbalance to our discipline’s history of extractive practice, seen in the physical movement of artifacts from excavation sites to foreign museums, and in the one-way transfer of knowledge from local communities to scholars. Discussions of heritage ethics and public archaeology revolve around the principle that heritage should be applicable, responsive, and responsible to local communities, or even driven and directed by local communities themselves (Atalay 2012; Chitty 2016; Colwell and Ferguson 2008). Places where the past is especially important to the making of the future—like post-genocide Rwanda—would seem to be apt locations for a thoughtful and reflexive heritage practice when engaging in community projects.

In Rwanda, the field of heritage production is dominated by the central government. National museums and memorials are part of the government’s efforts to establish a usable history for the country, where the politicized divisions between ethnic groups that were reinforced and reified during colonialism resulted in a devastating genocide in 1994 (Des Forges 1999). Today, the Rwandan government seeks to replace ethnic identity with national identity, using heritage to create a narrative of the past in which pre-colonial Rwanda is the source of a unified Rwandanness.

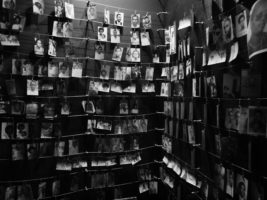

Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre. Dave Proffer/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Narratives about the past have been strongly centralized. Divergent historical interpretations are not only unwelcome, but actually criminalized through laws about genocide ideology. This term has become increasingly expansive. It includes not only direct incitements and genocide denialism but also deviations from the official discourse and certain kinds of political opposition. In this context, if civil society organizations or, for that matter, foreign heritage specialists or archaeologists wish to promote engagement with heritage, the space available for them to do in ways that challenge or complicate the official narrative is tightly circumscribed.

At the same time, heritage participation is not impossible. An array of development initiatives incorporate heritage; culture-oriented civil society groups exist; and the government-directed heritage sector undertakes citizen outreach. Is response to the official heritage discourse, statutory regulation of the past, and sweeping capacity of the government, Rwandans have protested heritage projects they oppose, such as when some groups of genocide survivors agitate against the display of human remains at genocide memorials. But many of the efforts promoted by calls to engaged practice—those that complicate and diversify views of the past or those which identify and aim to empower specific descendant communities, are politically untenable.

Genocide Memorial, Kigali, Rwanda. Olympus Digital Camera. Andy/Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Rwandan case should give pause to those of us with an interest in heritage ethics. It demonstrates how heritage is simultaneously of intense importance—in how many places can we say that heritage is understood as a life-or-death issue—and, because of that importance, how heritage can be intensively controlled by a strong central government that is unwelcoming of efforts to diversify, complicate, and democratize control of the past. Those of us with an interest in heritage ethics, should consider participatory heritage as a high-stakes endeavor. The very value of heritage itself can be a barrier to certain kinds of heritage practice, especially those which stem from the principles of participatory, engaged heritage ethics.

Annalisa Bolin is a student in the doctoral program at Stanford University and a 2018 winner of a Student Membership Award from the Archaeology Division.

Sandra L. López Varela is contributing editor for the Archaeology Division.

Cite as: Bolin, Annalisa. 2019. “Practicing Heritage Means Life or Death in Rwanda.” Anthropology News website, May 30, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1177