Article begins

A person that lives in a country shouldn’t be required to know another language to be able to sustain themselves. I shouldn’t have to say, “Wow, I was born speaking Spanish, but I have to learn another language to have a good quality of life.”

—Miguel (18 years old)

Miguel animatedly responded to the statement from Luis Abinader, president of the Dominican Republic, that “ningún dominicano que sabe inglés está bajo nivel de pobreza” (no Dominican that knows English lives below the poverty level). This headline provoked intense conversation among youth in a language and social justice course I developed with three multilingual educators at a nonprofit organization (Institute for the Future, IFF). As students noted, tourism jobs required English without paying minimum wage and were marked by exploitative labor conditions. Even the most precarious informal jobs—such as moto-taxi driver—required some English to interact with foreigners.

Throughout the 13 years I have worked in the Dominican Republic, I have observed the intimate relationships among language, race, and citizenship in the political economy of tourism and their effects on youth livelihoods. Dominican youth express frustration at seeking jobs unsuccessfully in their communities due to limited English. Many Haitian and Dominican of Haitian descent youth, despite speaking multiple languages, encounter difficulties finding jobs given legislation that restricts their access to citizenship and national identity cards. Yet, white foreigners—who speak little Spanish and/or have no legal residency paperwork—can secure or create jobs for themselves.

Most educational programs in the Dominican Republic are designed with the assumption that helping youth learn English will prepare them for local jobs in the tourism industry and ultimately improve their economic livelihoods. Yet what happens when youth are encouraged to shape their multilingualism toward an extractive labor market?

After working full-time for IFF on the Dominican Republic’s north coast for five years (2012–2017), I returned in 2021 for my dissertation research with this question in mind. Before developing the language and social justice course, I co-taught four English classes as part of IFF’s workforce development program. It became clear that for the 75 students in these courses, their multilingualism had different meanings than those found in English courses aligned with the service industry. Joa and Nelson were two students whose multilingualism defied notions of economic success underpinning most English programs in the country.

Joa

Joa was confused about being placed in the beginning level on the first day of English class. She had been switched from intermediate courses because she was late receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, a requirement to participate in the government-run customer service class that was part of IFF’s workforce development program. To illustrate her proficiency, Joa showed me the English sentences she composed on her phone to describe a typical day. Joa felt uncomfortable writing because she had more experience using English in conversation. She proudly stated that her dad—a well-known artisan—was multilingual and had spoken to her in English and Spanish since she was a little girl. He always pointed out how to say different things in English and even spoke a bit of French, German, and Italian. In Joa’s case, English had already been passed on intergenerationally from her father from a young age, even though he had become proficient in English as an adult. For many years, Joa used English in familial and community relationships and did not see it as necessarily instrumental for a job, in contrast to the English class’s purpose in the workforce development program. Her experiences defy dominant discourses that position English as a foreign language acquired most successfully through private language institutes. Her experiences also illustrate that English is not only accessible to the country’s elites but also may be used at home by students from more marginalized communities.

One morning, Joa was working rapidly on a presentation she would give in class about a monument in Santiago. She looked at me with tired eyes and said she didn’t have time to finish it the night before because she got home late from work. I asked where she worked, and she admitted that she had just quit her job at a restaurant. She offered that the job did not give her a fixed salary, and she was overworked, constantly doing tasks outside the job for which she was hired. She had decided that it just wasn’t worth it to continue.

Later that week, we sat at a restaurant on the beach where students practiced ordering their favorite juices in English. One of Joa’s peers, Nicol, jokingly said that they were all gringos now (a common refrain among students in the class that linked language to race and nation). I replied with a smile that they were Dominicans speaking English. Nicol laughed, and Joa added quickly, “Yo no tengo el sueño americano” (I don’t have the American dream). She affirmed that she had already decided to leave the country but preferred to go somewhere like Spain, where she spoke the language. Nicol also preferred Europe; she wanted to go somewhere to have new experiences and adventures. In many ways, they both saw their desire to leave the country as typical among youth in the Dominican Republic, but they also understood their choices were different from the norm because they did not want to go to the United States. Even having been exposed to English from a young age, Joa did not see English as necessarily playing a role in her ability to be successful in the future. However, she recognized constraints in the local political economy that might prevent her from realizing her dreams of opening a hospital in the community.

Nelson

“Sé algunas cosas y puedo defenderme en inglés” (I know a few things, and I can hold my own in English) Nelson shared during our conversation to assess his English level for course placement. I recommended him to the program coordinator for the intermediate English class and was surprised to find him in the beginning-level class on the first day. As a Dominican of Haitian descent, Nelson moved fluidly between Spanish and Kreyòl. In other courses, I had seen him play a crucial linguistic brokering and translation role for three of his peers who had recently migrated from Haiti. I wondered whether he had been placed in this class to continue serving in that role. All seven students of Haitian descent had been placed in this classroom. From my previous conversations with another teacher, I knew these students had shared that they often felt excluded in other classes. For example, I observed one student, in particular, defending his ability to speak Spanish when other students suggested he did not understand the language despite immigrating at a young age.

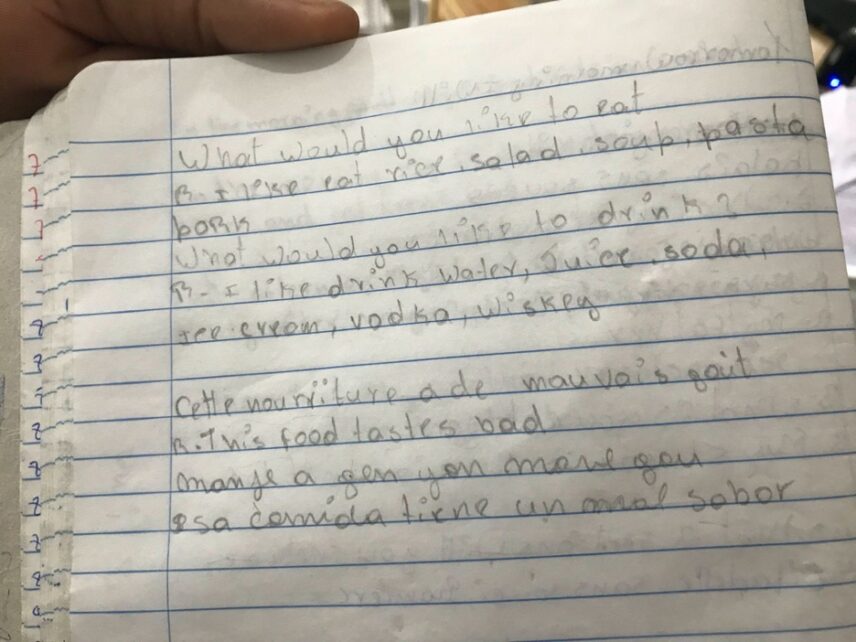

Throughout the English classes, I watched Nelson use Spanish, English, and Kreyòl to translate activity instructions for his friends and to generally share his knowledge of English (which he had learned in school) as they worked collaboratively on dialogues. When two of his peers were absent on the day students selected famous sites for a final presentation, he took a picture of the slide and shared the instructions with them. One day, when Nelson was absent, these same peers came to class without having the drafts of their texts. When I asked about the drafts, they said they needed to ask Nelson where they were. Nelson played an important role in and outside of school for his friends.

As one student, Pierre, presented about Palais Sans Souci in English, he asked me if he could say a few sentences in Kreyòl (as several students had similarly used Spanish in their presentations). When I said yes, he called Nelson to the front of the room. Nelson did live interpretation line for line for Pierre’s presentation. When Pierre read from his paper “se yon bel kotè,” Nelson interpreted it in Spanish “es un hermoso lugar” (a beautiful place). At one point, Nelson couldn’t think of the translation for a Kreyòl word on the spot, and he called out to the other Kreyòl speakers in the class for help. After much back and forth, nobody could come up with the word. Nelson glanced around the room, saw his peers becoming restless, and laughed and said, “Deja esa vaina!”—a distinctly Dominican expression indicating he wanted to move on. Sensing that the non-Kreyòl speakers in the class were losing interest, he diverted the conversation. Yet the change of topic did not detract from the Kreyòl speakers having had an uncommon opportunity to center their language practices in the classroom.

Nelson had initially confided that he was interested in learning English to work and to meet new people. These goals were complicated by the fact that within IFF’s workforce development program, the government-run customer service class did not allow students like Nelson without Dominican identity cards to participate. In addition, the program coordinator shared his worries about being able to secure internships for these students based on past experiences with local employers who were unwilling to hire them. Though these students engaged daily with multiple languages differentially valued in the local labor market—they often wrote in four languages in class—structural racism shapes their ability to find stable employment in the local labor market.

Joa’s and Nelson’s relationships to their multilingualism were more complicated than dominant narratives suggest. Neither fully accepted the belief that English was the sole pathway to economic mobility, nor were they unaware of the rampant discrimination and exploitation in the local tourism industry. Because of these realities, students desired—and carved out—opportunities to enact multilingualism on their own terms.

Tricia Niesz is the section contributing editor for the Council on Anthropology and Education.