Article begins

Ideas about sovereignty over natural resources remain trapped in a Cold War binary of market capitalism vs. state socialism, but both these systems are inadequate to the challenge of climate change. Recent political protests in Chile, drawing on indigenous imagery, point to a stringent need to rethink sovereignty.

The Soyuz symposium scheduled for spring 2020 was on the subject of sovereignty. This is a timely topic given that climate change is forcing us to reimagine sovereignty over natural resources. Chile is facing questions of sovereignty that will need to be addressed globally, as natural resources become scarcer and more unpredictable around the world.

In Chile and elsewhere, socialist ideas are making a political resurgence in efforts to imagine solutions to the social inequalities and environmental destruction produced by neoliberal capitalism. We owe this mode of binary thinking to the Cold War that has limited our political imaginary as a choice between socialism and capitalism. Yet in practice, the various forms of capitalism and socialism have one crucial aspect in common: they all treated natural resources as commodities to be extracted. In order to find new political solutions we must pay careful attention to how sovereignty functioned in actually existing socialist systems, and to understand how the claims to sovereignty that are being made in the streets transcend this political binary.

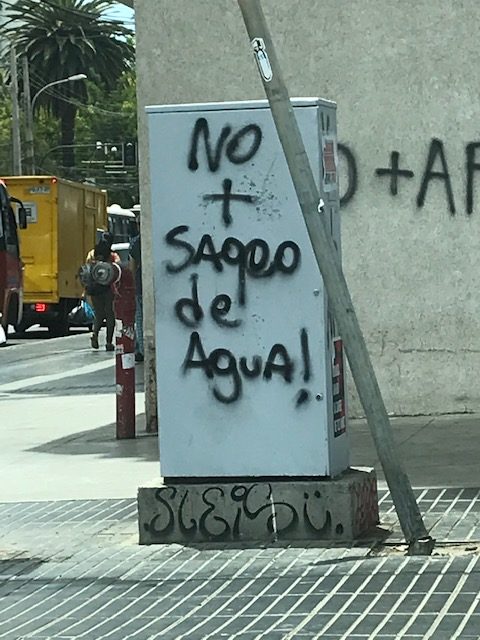

Image description: A rectangular, electrical switch box sits upon a concrete base. “No + saqueo de Agua!” is written on one side of the box in black spray paint. Metal grates surround it, and a portion of a busy street is visible.

Caption: Graffiti reading “No looting water” in Santiago de Chile. Justine Buck Quijada

I spent six weeks in Chile this past winter, where there have been anti-government protests since October 2019. I am not a specialist in Latin America. My work is on religion in Siberia, including how animist landscapes embed sovereignty in the natural world rather than in human political systems. I was in Chile for personal reasons, but a fieldworker’s habits are hard to shake. As I talked to local residents, I saw similarities between Chileans’ grievances and Indigenous critiques of property rights.

The protests, initially sparked by a hike in metro fares, are a culmination of decades of neoliberal privatization that rendered everyday life unaffordable for the many. Chileans pay for a privatized version of national health that is so underfunded that it is virtually impossible to access care. They pay into private retirement accounts that fail to provide livable pensions and pay outrageous tolls to drive on highways built by foreign companies.

Climate change, corruption, and the extreme commodification of resources like water produce a perfect storm that undermines both citizenship and the very property rights that neoliberal privatization supposedly champions.

Violent incidents between police and protestors were at the fore of international news coverage. The peaceful aspects of the protest movement that garnered widespread public support among Chileans have piqued much less interest. One of the key issues is natural resources. Specifically, access to water has joined health care, retirement, and education, among the things citizens insist they should have rights to. The attached photograph shows graffiti demanding “no saqueo de agua” (no looting water). Whereas authorities have accused protestors of looting, citizens argue that they are themselves being robbed of water access by powerful corporations.

Chile’s privatized water system means that distribution rights are licensed to transnational corporations. Citizens must obtain government permits to build a well, even on their own property. However, the central part of Chile, which includes the capital, Santiago, and the next largest city, Valparaiso, have experienced progressively worsening drought conditions over the last decade. In 2019, there was no rain at all. This year it rained, but not enough to reverse the effects of the dry spell, which has forced the government to consider rationing water for personal use. When rain was plentiful, agricultural exports, especially avocados and wine, seemed like an economic windfall. Now, however, as the central region turns to desert, access to water for avocados provides a perfect example of the intersection between climate change and sovereignty.

Avocados usually grow along rivers at the bases of Chile’s many mountains. With the growth of international trade, export corporations have expanded their plantations onto the cerros, the mountainsides. To obtain the tremendous amounts of water that avocado trees require, they dig wells deep into the hills, extracting groundwater long before it reaches the valleys. These wells combined with the recent drought to dry up local rivers that once supplied water to small-scale farmers living further downstream.

Driving anywhere in the central region, one crosses bridges over dry riverbeds between hills covered with green avocado trees, a stark visual representation of water access inequalities. My friend explained, “Corporations aren’t supposed to be able to do that. These hills used to be covered with native palms that are supposed to be protected. But they have friends in the Congress, so they get a permit for a well, and everyone else’s trees die.”

Those of us who work in former Soviet spaces know very well that state socialism did not do a great job in protecting the environment from exploitation either.

Climate change, corruption, and the extreme commodification of resources like water produce a perfect storm that undermines both citizenship and the very property rights that neoliberal privatization supposedly champions. Simply put, power differentials enable export corporations to get a disproportionate share of natural resources to the detriment of local residents, who will have to ration water, and small-scale farmers who produce for the local market. Without access to water, the latter’s sovereignty over their lands is rendered meaningless. They could neither grow food on it, nor could they protect the trees and plants which were slowly dying of thirst. “It hurts me to see them like this,” one woman said, as she gently stroked the dried leaves of a dying avocado tree. “Everything dry, everything dead.” Her sorrow does not express merely a property relationship but points to resource sovereignty as an existential question. Citizenship means very little if the means of existence can be expropriated.

The government has agreed to the protesters’ demand for a new constitution. Elections to choose delegates to write the new document have been postponed due to the pandemic. Water, mineral, and fishing rights are all at issue. The question facing Chile is one we will all have to answer: Will our political imaginations be up to the task of defining sovereignty over natural resources in a way that enables their conservation and just distribution?

Chile’s history is scarred by the binary choice between state socialism and market capitalism. For those who supported Salvador Allende, the first democratically elected socialist president, Augusto Pinochet’s coup in 1973 represented the foreclosure of a better future. For those who opposed Allende, the coup saved them from Venezuela’s present. Demonstrators drew hammers and sickles on buildings to highlight their commitment to socialist ideals, but many of those I spoke to felt corruption transcended political party or ideological affiliation. Socialism may appear to offer an alternative to capitalism, a vision of sovereignty in which natural resources are common property. However, those of us who work in former Soviet spaces know very well that state socialism did not do a great job in protecting the environment from exploitation either.

There are substantial differences, of course, between the democratic socialism of Europe and centralized planned economies. Both, however, like market capitalist liberal democratic systems, vest sovereignty in national forms, and treat natural resources as property. Overly simplified, in capitalist systems, the state guarantees property rights that are regulated by markets, whereas in state socialist systems, property rights are vested in the state, which redistributes these resources. Since the state represented the sovereignty of the people, there was no system to hold the state accountable for over-exploitation that led, for example, to devastating over-hunting throughout Siberia in the effort to meet production quotas. In European democratic socialism, states decide what falls to the market, and what to the state. In all three, natural resources are regulated as property, rather than a shared resource that must be managed in order to sustain life. In contrast, Indigenous treaty rights activists have long argued for the truth that climate change is forcing the rest of the world to acknowledge—that without access to resources, political sovereignty is meaningless.

If we are to reimagine sovereignty in a way that allows us to survive climate change, we need to overcome the tendency to treat socialism and capitalism as pure opposites and analyze instead how both state socialism and market capitalism produced unsustainable environmental extraction. Comparing the common failures of these systems, and considering the alternative visions of sovereignty imagined in their wakes, may offer a better path forward. Indigenous conceptions of sovereignty, which subvert nation-state forms and have long focused on access to natural resources offer a useful point of comparison. It is no coincidence that protestors in Chile have claimed the Mapuche flag as a symbol of protest.

Justine Buck Quijada is associate professor in the Department of Religion at Wesleyan University. She is the author of Buddhists, Shamans and Soviets: Rituals of History in Post-Soviet Buryatia.

Adrian Deoancă and Nelli Sargsyan are contributing editors for the Soyuz Postsocialist Studies Network’s Anthropology News column.

Cite as: Quijada, Justine Buck. 2020. “Resource Sovereignty Beyond Socialism and Capitalism.” Anthropology News website, October 23, 2020. DOI: 10.14506/AN.1519