Article begins

Street food finds a home in Mexican national baseball as fans gobble up peanuts, hot dogs, and tacos.

Ballpark vendors

When the Guerreros de Oaxaca baseball players take the field from April to August, fans are likely to be indulging in tasty concession food. The familiar faces and voices of dozens of hard working food vendors are an integral part of the Guerreros baseball community and experience in the city of Oaxaca de Juárez (population 300,000). These always friendly folks, aged from teens to late 50s, include independent vendors, restaurant employees that have concessions, and staff employed directly by the baseball organization. Some work on commission, others for a salary, and still others have permits to vend specific products.

View from the stadium. Jayne Howell

Vendors have witnessed many changes in the 7,200 seat stadium since 1996, when the first game was played, including a new scoreboard and the construction in 2008 of a roof that spans the central section of stands.

The scoreboard. Linda Harbert

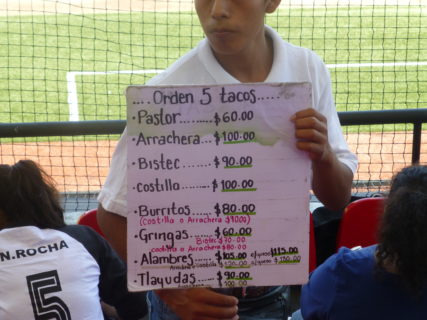

With 70 peso per ticket seats fans often buy food and drinks while it rains (19.25 pesos = $1 US). Although food sales are typically made in cash, a noticeable change in the 2019 season is that for the first time, beer can be purchased with a credit card. Another critical transformation in the food offerings over the years has been the increased visibility of local restaurants with printed menus.

A menu of street foods for sale. Linda Harbert

Local street food favorites

Puestos (stalls) beneath the stands sell freshly made local favorites: empanadas, tacos, tostadas, nachos, tortas, sliced fruit and coffee.

Concession workers at the Combinados or Alebrije Restaurant at the ballpark. Linda Harbert.

In what one Guerreros fan called a “constant parade,” vendors carry orders to patrons in the stands, or walk past carrying wooden boxes laden with candy, beer, fruits potato chips, donuts, and bags of nuts. Prices range from 10 to 175 pesos. Sales vary widely during the season, and for vendors of different products. On a typical night, collectively fans may eat over 100 donuts, bags of popcorn, or boxes of potato chips; and drink at least 100–150 glasses of beer, cans of soft drinks, and bottles of water.

“Sales are great when our team is winning, and there’s lots of emotion! When we [Guerreros] win, we [vendors] win.”

Beer vendor. Omar Rojas Hernández

Making a living

For informal sector workers earning commission, a precarious income and lack of benefits are the worst aspects of vending. On a slow night, earnings may be below the 102 peso daily minimum wage. Luckily, during what one interviewee called “a really, really good game” takings more than treble that. No one would argue that these folks earn every penny. A physical reality, one long-term vendor explained, is “you can get tired going up and down those steps. You get used to it, your body adapts. You get stronger. But you cover a lot of ground on foot, and it gets harder as you age. You see that at some point, some of the older vendors are no longer here. They just couldn’t do it anymore.”

Fans and vendors alike were saddened this past spring to learn that a popular elderly nuts vendor had passed away during the off season. There are many positives of working at the stadium. Because games start at 7:00 p.m. on weeknights and 5:00 p.m. on weekends, one can use vending to supplement earnings from a day job.

Selling nuts and popcorn during the game. Linda Harbert

During the off season, a number vend in Oaxaca City’s zócalo (central plaza), during political marches and protests, or at folkloric fairs and festivals around the state. Another benefit is that vendors meet a wide array of people, and in some cases establish friendships with other vendors and longtime Guerreros fans. Others enjoy working with their immediate family members, and many get a chance to chat with relatives who also sell in the stadium.

Tostadas with guacamole. Linda Harbert

Those who love baseball appreciate seeing all the games. Most salient to my long term research on education and employment, parents emphasized that vending has enabled them to provide their own children with formal education. One father of three said, “We’re all parents, and any of us would tell you the same thing: I’m working here to give my children a better future.” Indeed, a number of youths and young adults who work with their parents are studying accounting, architecture, engineering, and law at local universities.

In the anthropology of sports, including an issue of Anthropology News, such research about food and the workers who serve it in sport venues is rare with scant mentions in Australia, Bermuda, Japan, and the United States. For anthropologists, Guerreros games offer an opportunity to study sales, consumption, and employment in the contexts of overlapping social relationships, including bonds within families and the camaraderie that develops between vendors. Moreover, there is food for every taste. The games are always fun, including when the home team loses. Of course, it’s even better for fans and vendors when the Guerreros win.

Jayne Howell is professor of anthropology and co-director of Latin American studies at California State University Long Beach. She conducts research on education, informal and formal employment, cityward migration and urbanization, gender role change, tourism, social movements, and Isthmus Zapotec women in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Walter E. Little ([email protected]) is contributing editor for the Society for Economic Anthropology’s section news column.

Cite as: Howell, Jayne. 2020. “Selling Food and Watching Baseball in Southern Mexico.” Anthropology News website, January 16, 2020.