Article begins

Bubble Gum is an all-female choir founded by Pippa Bacca, a performance artist and environmental activist, tragically famous for her violent death on March 31, 2008, during her performance of Bride on Tour (Le spose in viaggio) in Turkey. She was 33.

The goal of her last performance was to pass through multiple stops on a journey to Jerusalem. Kicking her tour off in Trieste, Italy, she took time along the way to meet with midwives, held to be the feminine symbols of life and maternity. The encounters between the artists (Bacca and one other companion artist travelling with her) and the different midwives saw the repeated performance of two symbolic moments: the midwives lined Bacca’s wedding dress and Bacca, in return, washed their feet.

The performance of Bride on Tour had been carefully prepared over the course of a year. The overall message was one of cross-border peace and the artistic objective was to create a symbol of that with a presentation of photographs taken during the journey and a presentation comparing the dress Bacca had lined by the different midwives against the original design of the dress stored in the workshops of the Italian clothing brand Byblos.

Bacca was buried with the dress she wore on her tour as it was the dress she wore at the time of her death.

Her violent death contributed to divesting Bacca of her personality to transform her into a public icon. We offer a different vision of her oeuvre, discussing Bubble Gum as a fundamentally artistic undertaking and bringing back into view what it created. The choir, its songs, and exuberant performances extend the possibility of a permanent work of art that could allow successors to breathe new life into the panoply of characters (living and disembodied) and revitalize or even “resurrect” the now absent artist.

Bubble Gum in historical and political context

Bacca developed her talent with the Coro di Micene, an historically anarchist choir in Milan. The idea behind Bubble Gum would be as simple as it was subversive: for what reason should left-wing women have to present themselves as “ugly” to be taken seriously? Bubble Gum was born to overthrow this norm, to create opportunities for activist and cultivated women to play with aesthetics and different types of femininity.

The possibility of a demystified feminine eroticism presentable to the public was only raised in the world of contemporary European art in the 1950s, with the French artist Niki de Saint Phalle. Saint Phalle based her art on the idea that it was possible to be a woman, a successful artist, a feminist, and a vamp at the same time and without diminishing oneself. The same philosophy drove Bubble Gum in their use of ironic and erotic imagery as a counterweight to the Italian political context of the time. Just as Saint Phalle did in 1950s France, Bubble Gum roused a countercultural resistance to local notions of femininity. The art historian Catherine Dossin has said of Simone de Beauvoir and Saint Phalle that “Their femininity actually gave them more serious credibility: in the French context, the masquerade of hyper-femininity was a political position—an effective counter-hegemonic and counter-patriarchal stance” (2010, 34).

The choir was born in the summer of 2005, after the arrival to power of what was called the putocrazia (a portmanteau of “plutocracy” and “whore”) of the then prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi.

Particular ideas of femininity were taken hostage by left- and right-wing political forces who precipitated a polarization between two feminine clichés: on one hand the “whores” (those on Berlusconi’s side, the scantily clad young women or “velines” of “bunga-bunga” parties) and on the other hand, the moralizing shrews. All freedom to express femininity (including female sexuality) was reduced to those two opposing poles. Bubble Gum took on the image of the 1950s pinup, the music hall entertainer, the burlesque performer and the female diva. The choir would open up the possibility for, and go on to champion, a femininity reinvested with the excessive and the grotesque, and go on to remind women of their power to make demands and ensure they are met, with each own unique style.

Twenty-five minutes of madness on stage!

Bubble Gum is a performance, at once offbeat, ironic, and dreamlike. Each performer comes on stage in character, a being that exists only during the performance, disappearing with its end.

Bacca’s real name was Giuseppina Pasqualino di Marineo. As her Bubble Gum alter ego, she was Eva Adamovich, joined by a bawdy cast of characters: Betty Bu, Citofonare Giusy, Demi More, Gilda, Ginger, Greta Ginzburg, Lulù Tutù, Madame De Wicca, Minnie, Misù Bijù, Rosemary Grosswein, SantaRita Dal New Jersey, SportyBubble, Tatì, and Wendy. They rarely all sing at once, but rather act as an adaptable ensemble that adjusts itself to the number of participants for each performance.

There were no criteria for joining the choir: all women who wanted to sing and have fun were welcome. Nevertheless, Bubble Gum retains the classic choir structure of three feminine voice types: soprano, mezzo-soprano, and contralto. They sing a capella. Nobody actually knows musical theory. The rehearsal directors are volunteers who arrange well-known songs and jazz standards for the choir. The musical repertoire is composed of three “canoni” that open each concert: “Dam Di Dam,” “Swing your Arms,” and “Doobie Doobie.” The program continues with “Summertime,” “Over the Rainbow,” “Love Me Tender,” “Besame Mucho,” and, following Bacca’s death, “Moon River” (under the guise of it being her birthday song).

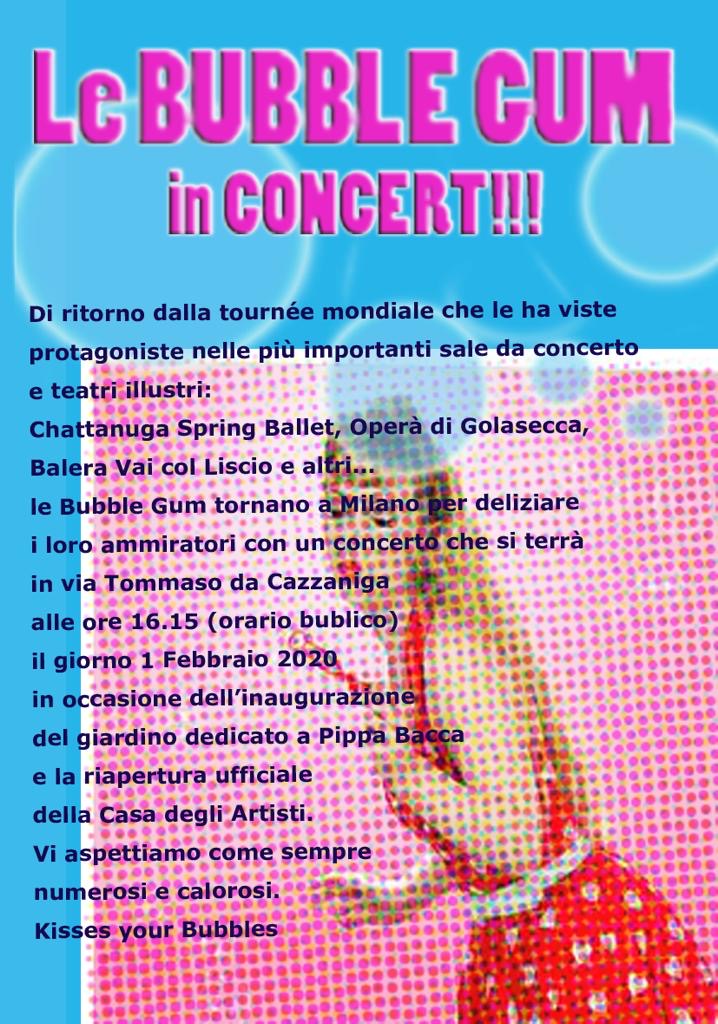

The choir takes its mark without announcement. The performers wearing dresses and heels, excessive makeup, false eyelashes, glitter, and colorful garb. Adamovich standing out with her black parakeet and fake ostrich feather boa (since her death all the costumes include a boa). They organize themselves in a semi-circle facing the audience. One of the members (originally Adamovich) presents the group as “big stars” and boasts of Bubble Gum’s long tour to the four corners of the world where they are in high demand from countless fans and where they are protagonists in amazing adventures. Then, on with the show! The finale is always “Besame Mucho.” And the performers exit the stage.

For two years up until Bacca’s death, the choir gave concerts all over Italy: in Florentine squats, in Milan to inaugurate exhibits at La Biennale museum, at the Lac de Garde for a stop of the Mille Miglia motor race, for artistic openings, in an Italian alpine club in the middle of the Apennines, for marriage ceremonies, and at Bacca’s funeral on April 19, 2008, in front of the San Simpliciano church of Milan.

In 2008, according to her obituary in Corriere della Sera, Adamovich thus departed for a never-ending tour of the Bahamas. After a period of mourning and disarray, the choir started performing again. But how could they sing with an empty space among them?

Return to the stage

Today, the choir performs for commemorative events, typically after being contacted by Bacca’s family. The original features are all there: the same songs, the same aesthetic codes, the same zany surrealism. But 12 years on, the mood is still one of collective mourning.

The repeated spectacle serves as a kind of mediation between the absent member and the living characters. The audience finds itself before an ensemble of characters that are both fictional and flesh and blood with the ability to reveal the ontological condition that blurs the limits between the living and nonliving (Pecci 1999, 95). The performance that once invoked a different kind of feminine presence, one that took issue with the figure of the “woman” being imposed in the Italian cultural context, now allows for the possibility of reactivating the group’s bonds to the dearly departed. The choir with its imaginary characters is now the materialization of the past link to Bacca. In the liminality of the performance, in her absent presence, Adamovich lives on.

The artistic performance allows a re-elaboration of the loss, but at the same time it brings out a new ontological status acquired by Adamovich, neither alive, because her body is no longer among the living, nor dead, because the power of the evocation vivifies her presence.

Bubble Gum is a performance, at once offbeat, ironic, and dreamlike. Each performer comes on stage in character, a being that exists only during the performance, disappearing with its end.

In his article on the liminality of the corpse, David Le Breton asks, “Quelle sorte d’êtres sont les morts?” (What kind of beings are the dead?) (2013, 36). A person’s death always brings with it new meanings on the nature of the relationship with the deceased.

In the early years, the choir rehearsed at La Casa degli Artisti (the House of Artists), a squat in a three-story building built in the early twentieth century as residences for struggling artists at l’Accadamia di Brera in the Corso Garibaldi area in the middle of downtown Milan. The site was designated for luxury apartment developments, and in September 2007 the police evicted La Casa’s residents. It took strong popular mobilization, facilitated by the city’s shift to the political left with the election of mayors Giuliano Pisapia (2011–2016) and Giuseppe Sala (2016–present), for La Casa to find rehabilitation and transformation as a public space for art and culture. The official inauguration of the new Casa degli Artisti on February 1, 2020, and consecration of a garden in Bacca’s name provided Bubble Gum with a new chance to take the stage before a public audience.

The funeral took place, everyone was present, her coffin was buried in the small family chapel. Giuseppina Pasqualino di Marineo is dead, no doubt. But we desire continuing relations with her, and the Bubble Gum shows allow us to share and continually revitalize the relationship between the group and its member, Adamovich. Perhaps this is the new substance our friend and founder is now made of.

It is only among the different characters and their ostrich boas that Adamovich can take back her identity and integrity. It is no longer the unbridled bride who died in an unknown country who we commemorate, but the liveliness of the artist star that continues to perform in the looping cacophony of “Dam di dam di dam… .”

We’d like to give special thanks to Marco Dall’Omodarme, Michael Houseman, Marika Moisseeff, and the participants in the “Atelier Mediations Relationnelles” organized by Houseman and Moisseeff.

Endless gratitude to Pippa.