Article begins

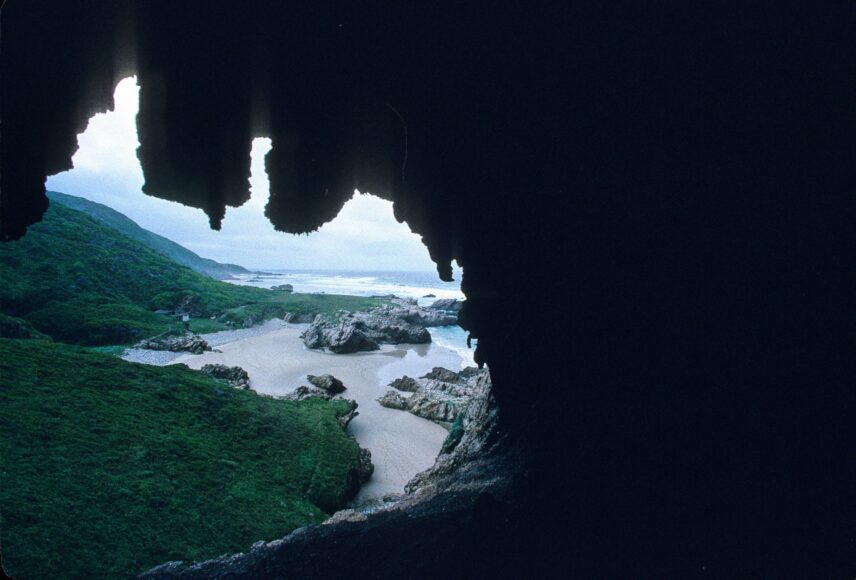

While excavating at the Klasies River archaeological site, with howling winds, the sound of waves crashing, and cormorants and black oystercatchers calling in the background, we wondered which sounds our ancestors living in the cave would have made. Did they tell stories while they prepared and ate the bounty from the sea and thicket forest? Did they sing and dance and make music with instruments made from the bones of the animals they hunted?

The southern Cape coast is a world-renowned site for archaeological shell middens from the last 120,000 years, which tell the story of our ancestors’ symbolic achievements from the deep past. But on Stone Age sounds and music these middens have, so far, been silent. Putting our heads together, we contemplated which artifacts from Klasies River and other sites could bring Stone Age sounds alive in the southern Cape. Would we be able to identify music making, the quintessential human symbolic expression that is universally present and fundamental to all human societies?

What is music? For psychologist Steven Pinker, it is “auditory cheesecake,” nothing more than an evolutionary by-product; and for others, such as cognitive musicologist David Huron, it is a “nebulous rubric.” A definition that facilitates the deep time investigation of the evolutionary origins of music is that it encompasses “intentional action in which complex, learned vocalizations (and/or instrumentally produced sound) are combined with the movement of the body in synchrony, or entrained, to a beat.” However, defining music in a more comprehensive way did not help us to come closer to Stone Age sounds in the southern Cape. The musical expression shared by all humans—synchronous rhythmic movement or dance and singing—leaves no physical traces. It was also no surprise that no Stone Age musical instruments from this area are known, as finding preserved artifactual evidence is akin to a miracle, given the preservation bias. Today and in recently known societies, most musical instruments are made from perishable organic materials like wood or reed that preserve for decades at most.

Our own search for music thus began with the less ambitious endeavor of finding sound-producing artifacts from Klasies River, familiar to Sarah as the site for her human origins work and well known for its 21 meters of archaeological midden material that reveal secrets of our ancestors’ innovative abilities. These include early utilization and processing of ochre, bone tools, and early bow and arrow technology. John Wymer, the pioneer who first excavated the Klasies River cave in the late 1960s, left a vital clue. He described a dual-holed bone implement that tapers at both ends, from midden layers dating to around 4,500 years ago, hypothesizing that this might be a wirra wirra. A wirra wirra is a flat disk with two holes in the center through which string is strung that is rhythmically pulled and released to produce a whirring sound. Other names for a wirra wirra are spinning disk, buzzing disk, whirring disk, and woer woer. At this point serendipity played a hand. Both Sarah and researcher Neil Rusch discovered that they had applied independently to the Iziko Museum in Cape Town for access to the artifact, but several attempts to find the wirra wirra proved unsuccessful. Fortunately, Wymer left excellent notes, and, since he was a trained draughtsman, the illustration he produced was accurate in every way.

We needed experimental research to expand further on Wymer’s hypothesis. Searching for Stone Age sound experimentally involved careful design, collaboration, and teamwork. We called in several colleagues to undertake actualistic research. This involves the investigation of past human actions, in this case sound production, through modern-day experiments, the results of which may support or falsify the hypothesis put forward. Actualistic research through experimentation has become one of the main ways to generate hypotheses on human behavior from the deep past (see for example Marreiros et al. 2020). But as trailblazing experimental archaeologist John Coles discussed in 1979, it is difficult to fully reconstruct the past. The experimentation firstly involved making replicas of possible sound-producing implements. Neil replicated the pieces that we studied, having recreated sound-making implements before. The replicas were used in various ways to make sounds, according to ethnographic descriptions. The buzzing or whirring sounds were recorded by Simon Kohler in the FIELD Sound studio in Cape Town. Another vital aspect was the involvement of archaeologist Justin Bradfield to study the use-wear traces on the experimental artifacts and compare this to the archaeological use-wear, in the laboratory at the Palaeo-Research Institute at the University of Johannesburg. Justin taught Joshua how to identify use-wear traces and together they painstakingly identified and described the use traces on the archaeological pieces and the replicas made by Neil. The use-wear traces that were identified include striations, polishing, and rounding on both the archaeological pieces and the replicas.

Joshua spun replicas of the Klasies River spinning disk made by Neil for many hours using various types of string, sometimes to the annoyance of his housemates. Once one has mastered the art of exerting just the right pulling and releasing energy, the buzzing sound resembles the sound of bees or even breathing. The spinning disk replica produced frequencies of 52 to 200 Hz. Together with three colleagues, we spun wirra wirra replicas in the Klasies River cave, triggering a truly magical sonic experience. The resonant qualities of the cave enhanced the sound to a throbbing sustained whirring emanating from within the depths of cave, the crashing of waves on the pebble beach outside joining and competing with our spinning sounds.

Fortunately, four bone “pendants” were found in the same context as the nonsymmetrical wirra wirra from Matjes River. These oval bone pendants, thought to be grave goods, have a single hole at the top and vary between 58 and 93 mm in length. Two are oval shaped, one is somewhat wider at the end, and another is snapped. Pendants are frequently interpreted as such, based on their similarity to modern jewelry, but, as actualistic research expounds, morphology does not necessarily imply function. Single-holed flat disks from the archaeological records of Scandinavia and Europe were shown to have been bullroarers.

Once one has mastered the art of exerting just the right pulling and releasing energy, the buzzing sound resembles the sound of bees or even breathing.

Bullroarers are flat disks with a hole at the one end, which are rotated or whirred above the head or in front of the body at the end of a piece of string. Bullroarers emit a strong whirring sound that pulsates—the larger the disk, the lower and stronger the pulses of sound—emitting a haunting sound. They are still played in some areas of the world, such as Namibia and Australia. Neil also made and tested these implements through a cleverly designed mechanical arm that swung them in bullroarer fashion for extended periods of time, and Simon recorded the sound. The use-wear analysis showed that only the largest pear-shaped archaeological pendant had use-wear identical to the mechanically spun replica. The use-traces are within the lateral sides of the hole of the archaeological implement, showing that this must have been swung by a Stone Age ancestor. This piece is similar to archaeologically known smaller bullroarers, creating frequencies of between 55.55 and 76.92 Hz. That bullroarer playing was an established tradition in the Stone Age of the Cape region is suggested by a group of bullroarer players depicted in the rock art shelter from Doring River, Cederberg.

Joshua played this bullroarer replica in the Klasies River cave. His experience confirmed that playing a bullroarer requires sustained energy to swing the implement above the head. The whole body is involved and stamina is required to produce continuous sound. Writing about the aeromechanical and aeroacoustical aspects of bullroarers, scholars Michel Roger and Stéphane Aubert describe the intricacies of producing sound with these implements. While he was swinging the bullroarer, Joshua could not hear the sound produced but the rest of us who were present in the cave could hear it very well.

The whirring pulsating sounds produced by the replicas of the archaeological spinning disk and bullroarer, when enhanced by resonance of the cave, created haunting sounds. Especially the bullroarer, which created a loud and unearthly aural illusion when heard outside the cave. What role could such sounds have played in the Stone Age? There are records of recent and current groups that play the bullroarer. Several Namibian groups, for example, the Uukwaluudhi, the Kwanyama, and the Ju|’hoansi are known to use the bullroarer to call the rain and in initiation ceremonies; it is also associated with mythical creators and god. Bullroarers were used by the |Xam Bushmen for manipulating bees, as the sound resembles swarming bees. One may further speculate that buzzing sounds are part of the experience of altered states of consciousness and enhanced states of association, and that bullroarers could thus have formed part of the otherworldly experiences of past societies. Another researcher, G. T. Nurse witnessed the Kalahari San Bushman playing a bullroarer during a music performance. This presents a challenge when interpreting archaeological artifacts because a single artifact may have various uses.

The pulsed whirring sounds of the bullroarer and spinning disk that we describe here are not necessarily “music,” and thus we have not been able to fulfill our original wish. But one has to keep in mind that the idea of music differs vastly between various groups today and in the past—a challenge to any attempt to come up with a universally applicable definition of music. The bullroarer, for example, was definitely seen as an integral part of Bushman music. This is the first description of a tangible Stone Age spinning disk and bullroarer from the southern Cape. Our experimental research shows that it is possible to add a provocative aural dimension to the archaeological connection that we currently have to our ancient past in this region. The southern Cape is well known for telling the story of our ancestors from the deep past; our research has added a chord that links to sounds of the past.

Further archaeological evidence from the region shows that the past was far from silent. A handful of sound-producing artifacts were recovered from Southern Africa. These include possible Later Stone Age bone flutes or whistles from Matjes River, Nelson Bay cave, and Bonteberg shelter in South Africa, but this still needs further verification. The last 2,000 years, known as the Iron Age, produced more archaeological musical instruments, which include two clay whistles from K2 and Mapungubwe in South Africa and iron bells or gongs from Zimbabwe, Zambia, and South Africa. Late Iron Age mbira keys were recovered at Ingombe Ilede in Zambia and from Great Zimbabwe sites. A spectacular ivory trumpet with a blow hole and some decorations has been recovered from the Mozambique coastal trade site of Sofala. Rock art provides further tantalizing clues to possible musical instruments from the deep past, including musical bows, hand and leg rattles, bullroarers, and flutes.

These archaeological instruments point to a long and noisy history of sound or music production in Southern Africa. The buzz of the bullroarer and spinning disk bring sounds from our deep past alive in the present. What acoustic connections might future discoveries and actualistic investigation reveal?