Article begins

University faculty and staff employ raciolinguistic ideologies to police Asian students and their language.

Have you ever been in the United States and heard people speaking a language you didn’t understand? Did it bother you? Have you ever thought about why it bothered you? For folks who might tell those people to speak in English, where does that entitlement come from? Why do some people feel they have the right to tell others how or what to speak?

You may be surprised (or not if you read the news) that policing people to speak English also happens on US college campuses. In January 2019, Megan Neely, an administrator in the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics MA program at Duke University, was asked to step down after warning Chinese students in her program that there would be professional consequences, such as losing out on internship opportunities, if they did not speak English while in their main research building on campus or in any other professional setting. In an Inside Higher Ed opinion piece, Susan D. Blum, an anthropology professor at the University of Notre Dame, provides the historical context of language policing in the United States, how it played out on Duke’s campus, and how it plays out in the greater everyday milieu off campus. She explains how Chinese students have recently been singled out with the current Trump administration waging a trade war with China and with Chinese products from companies like Huawei being banned for accusations of espionage, among other instances in which politics and ideologies target minoritized speakers.

As part of a research team at Oregon State University (OSU), my colleagues and I have found that Asian students are also being targeted at our institution. At OSU, internationalized students are often told—implicitly through signage and explicitly through spoken language—to speak only English, despite the evidence that translanguaging, the use of two or more linguistic codes, supports second language learning and general academic comprehension. In fact, when students walk into the Learning Center at INTO OSU—a private-public partnership housed in the International Living and Learning Center where students can take English classes and/or live on-campus in an “international” environment—they can see the following image prominently displayed near the seating area where students await their tutoring appointments.

Signs displayed in the waiting area for tutoring appointments at the INTO OSU Learning Center at Oregon State University. Jason Sarkozi-Forfinski

Apart from implicit language policing as the image suggests, students have shared stories that reflect the differing degrees of policing at OSU. According to their stories, not only are students chastised for speaking Chinese at work, but they are also called out for not speaking English well enough (or, given my subsequent research example, one could say White enough), oftentimes in front of their peers.

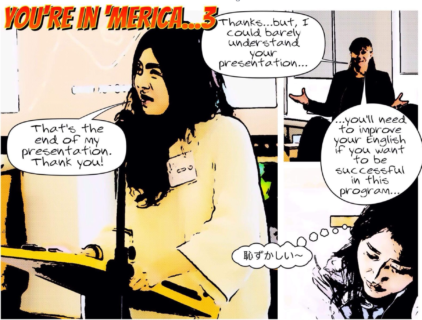

As part of a project to map the linguistic landscape of OSU, our research team examined, among issues of race and racial bias, attitudes toward language use on campus. One question we asked our participants was, “Have you ever experienced discrimination on campus?” OSU student Midori (pseudonym) reported experiencing discrimination in the classroom when a professor ridiculed her in front of her classmates, telling her that she needed to improve her English. The teacher claimed that her accent was too difficult to understand. Why did the teacher feel that is was alright to criticize Midori’s English ability, especially in front of her peers? Was Midori’s English not good enough or rather was it not White enough?

Midori, born in Japan and educated in English in various international schools throughout Asia and the Americas, being told her English isn’t good enough. Jason Sarkozi-Forfinski/Flipsnack, 2019

The experiences of Huang and Ellen (pseudonyms) also illustrate examples of racialized linguistic discrimination.

Huang is a second-year student from Southeast Asia who used to work at West Dining Hall. Having Chinese-speaking co-workers, she would often chat with them in their common first language (L1), Chinese (Mandarin), until one day their supervisor prohibited them from speaking it. The supervisor justified the prohibition claiming that she needed to be able to understand them in case they needed help and later confessed that she also wasn’t sure if they were talking badly about her.

Huang, from Southeast Asia, being scolded for speaking Mandarin Chinese with her coworkers. Jason Sarkozi-Forfinski/Flipsnack, 2019

Another Asian student, Ellen, told me about the time when she was threatened to be charged with a menial task for not speaking English. At the time of the incident, she was preparing vegetables for the salad bar with a Chinese-speaking coworker. In Chinese, Ellen asked her coworker if there were any more cucumbers. The manager, a White woman from Louisiana, must have overheard her speaking Chinese because later she approached Ellen and told her that she should be speaking English unless she wanted to be put on dish duty, a job that apparently was not highly sought after.

Ellen, from China, being threatened with menial labor for speaking Mandarin Chinese with her coworker. Jason Sarkozi-Forfinski/Flipsnack, 2019

Monolingual English speakers may have a hard time understanding why asking someone to speak English at the workplace would be problematic. After all, we are in the United States. But then, the United States does not have an official language; neither does Oregon nor OSU for that matter. While we note that language use, even in the workplace, is always flexible since people joke around, shift among different styles, or use mock languages, among other linguistic strategies, based on our research team’s findings, we argue that the discriminatory acts committed by the supervisors from both stories are connected to racialized bigotry, based on the notion that while in the United States one should use English at the workplace. We argue this because we found that it only applied to folks that were racialized as non-White.

Why does this happen at OSU and other college campuses across the United States?

White public space is a concept that Jane Hill describes as “[being] constructed through intense monitoring of the speech of racialized populations such as [Chicanxs, Latinxs, Blacks, Natives, Asians, and internationalized students] for signs of linguistic disorder.” Fundamentally, people of color (POC) who use languages other than English, or who speak English with an L2 accent or a stigmatized L1 accent (like Black English), are subject to heavy monitoring of their speech. As Gregg argues in “What Ta-Nehisi Coates Taught Me About ‘People Who Believe They Are White,” self-identified White folks, like the manager from Louisiana, listen to these people who they racialize as non-White with an ever critical ear, and some, according to our research, claim to “shut off,” or stop listening, when they hear a so-called “foreign” accent.

When we combine the concept of White public space with raciolinguistic ideologies, we can see why language policing is so prolific on US campuses. Nelson Flores and Jonathan Rosa argue that raciolinguistic ideologies “produce racialized speaking subjects who are constructed as linguistically deviant even when engaging in linguistic practices positioned as normative or innovative when produced by privileged [W]hite subjects.” In other words, in White public space, when POC don’t use the language or accent that is expected of them, i.e. (White-accented) English at OSU, their behavior is considered deviant or different from what is “normal” or “morally correct.”

What can internationalized students do to protect their linguistic practices?

After the incident at Duke, students created a petition to raise awareness of the issue. At OSU, our research team created a glossy zine, from which the above images were taken, to be distributed around OSU’s campus, with dining hall student employees and managers in mind. The zine details resources for students to report incidents of bias and provides information from the US Department of Labor so that managers can understand when it is acceptable to limit an employee’s speech to English. After the zine was distributed, we were contacted by two of the top administrators in housing and dining and discussed ways to move forward, especially focusing on how student employees can be informed of their rights and other resources beyond being given a gigantic orientation booklet that uses language that may not be accessible to all levels of English users. However, much more needs to be done, namely creating more resources for people to become more aware of how language is not only a material object but also a process and a social practice. Also, there need to be resources that help folks be self-reflexive about their own language ideologies and those of others. If we can’t do away with language policing, at least we can recognize when it’s happening, engage it critically, and through those processes perhaps reduce its presence.

In the end, ideas about language, especially about which language is “(un)acceptable” when spoken by certain people in certain contexts, are also ideas about race. When these ideas become institutionalized, they can carry additional authority. Thus, policing language needs to be understood as often constituting a racist practice, much like the Muslim ban, the detaining of POC on the southern border of the imagined community that is the United States, and other abhorrent racist practices that have always been commonplace as part of European colonization.

Jason Sarkozi-Forfinski, ABD, is a former PhD candidate in anthropology at Oregon State University. His research focuses on raciolinguistics in the United States and on disseminating anthropological findings to broader audiences.

Catherine R. Rhodes ([email protected]) is contributing editor for the Society for Linguistic Anthropology.

Cite as: Sarkozi-Forfinski, Jason. 2019. “Speak English or Else You’ll Be Put on Dish Duty.” Anthropology News website, July 18, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1226