Article begins

As they pursue thematic or regional specializations in the work of anthropology, several sections of the American Anthropological Association represent distinctive groups as well. What about older anthropologists? The Association of Senior Anthropologists (ASA) was founded almost thirty years ago, at that time primarily to address conditions that made it difficult for “emeritus professors” to continue their academic activity (Schwab 1990). Membership today includes adjunct scholars and many who have found employment outside of academia. Advocacy for physical, financial, and institutional accessibility continues to be an important but relatively small part of what the ASA does. Although advanced age may curtail some activities, anthropology must rank high among livelihoods with practitioners who never really retire.

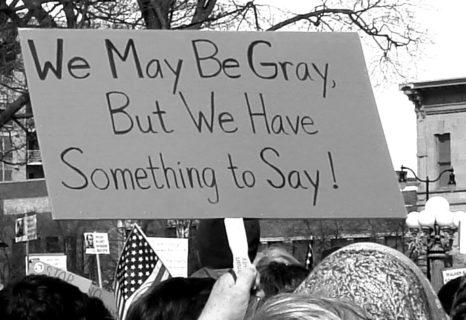

GraySay Placard. Herb Lewis.

This is where living history comes in. The ASA supports explorations of the anthropological past as it is embodied by elders. One precursor is a collection of biographies in Totems and Teachers (Silverman 2003 [1981]). Compiled many years ago by Sydel Silverman, a long-time ASA member who passed away last month, it examines the ideas and influences of some of the discipline’s foundational figures. The accounts show how personal attributes and surrounding conditions shaped intellectual and institutional initiatives in particular times and places. Another example is The Tao of Anthropology (Kelso 2008), a compilation in which ASA members and other anthropologists near or in retirement reflect on their careers. The ASA regularly sponsors AAA Annual Meeting events focusing on anthropologists who have driven changes in anthropological purposes, practices, topics, findings, and applications. One benchmark is Expanding American Anthropology, 1945-1980 (Kehoe and Doughty 2012), a collection of articles based on session papers presented over several years. As have subsequent decades, that transformative postwar period produced innovative anthropologies from which we can draw cautionary tales, as well as inspiration for new departures.

In addition to offering glimpses of our predecessors, ASA sessions have revisited the contexts and orientations that shaped our own careers. Recent panels have included Schools of Anthropology, First Fieldwork, Omissions and Silences in Ethnographic Fieldwork, Elders in the Field, and Fieldwork at the End of the Day. The recollections stimulate both senior and younger colleagues to scrutinize their anthropological experiences more closely. Relevant details may have been nearly forgotten, more meaningful than realized at the time, left under-theorized, and they eventually manifest in ways that could not have been foreseen.

The ASA treatment of living history moves from cohort to cohort down the line. Early-career anthropologists join us to draw their own lessons from historical investigations. They have contributed studies of ancestral figures and have served as our interlocutors in a series of panels called “Conversations across Generations.” Face-to-face interactions spill over into informal conversations at the luncheon that is part of the ASA business meeting each year. Field trips, moreover, introduce us to the living history surrounding the venues of the annual meetings.

More than antiquarian forays, such exercises in historicism infuse the current practice of anthropology with a fuller appreciation of its rich and largely untapped heritage. Virtual excavations of earlier projects reveal vestiges of unexamined assumptions and possibilities for the here and now. Learning the history of anthropology from its practitioners’ perspectives, we and those who follow can better understand the appeals, pitfalls, and achievements of differing approaches. In my case, for instance, familiarity with the agendas of environmental anthropologists, along with their publications, helps me draw more selectively from elements in the lineage running through cultural ecology to human ecology to political ecology and beyond. Ways in which such successive sub-specialties reflect their zeitgeist become more apparent in retrospect.

All anthropologists can embrace their distinctive identities as subject matter for research into the perpetually unfolding history of the discipline. The past we confront remains open. Origins of ongoing influences remain to be discovered over the course of a career. Having lived through a series of historical episodes, senior anthropologists are positioned to evaluate what they found useful at earlier junctures but had to jettison later. Recalling what they have retained or recovered and then incorporated in their later practice, they share vernacular kinds of knowledge drawn from past eras to create a more cumulative and well-rounded anthropological tradition.

Please review the program for this year’s Annual Meeting and participate in ASA activities in Vancouver, BC. I urge anthropologists at all stages of their careers to become members of ASA. Having been recruited well before I considered myself retired, I can attest to the benefits. Exposure to the personal reflections on continuities and changes in the work of anthropology constantly reinvigorates my own approach. Join the rest of us in making your own contributions over the coming years to the ASA’s explorations of living history. Keeping at it, we all become senior anthropologists sooner or later, each with a unique accumulation of experiences and understandings to share.

Jim Weil is a research associate at the Science Museum of Minnesota and president of the Association of Senior Anthropologists. His quarter century of field research in a Costa Rican ceramic artisan community continues, shifting with the circumstances.

Cite as: Weil, Jim. 2019. “Supporting and Promoting the Living History of Anthropology.” Anthropology News website, April 22, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1145