Article begins

Our experience with games at the American Anthropological Association Annual Meeting goes back many years—with Nick Mizer running table-top RPG sessions at the meeting in 2015. AnthropologyCon began at the 2017 AAA meetings in Washington, DC, and premiered a format that would be used in subsequent AnthropologyCons―a workshop followed by a gaming session. The inaugural session also initiated another practice―enlisting the expertise of games scholars to present and to organize workshop sessions, beginning with our coauthor Anastasia Salter. In 2018, in San Jose, we held AnthropologyCon at the Hammer Theater with playtesting back at the conference hotel. Finally, the 2019 AnthropologyCon in Vancouver (and the last before the pandemic) featured a workshop on gaming with Twine (led by David Gaertner), together with game-play opportunities. Will there be another workshop in 2022? We hope so, and, with it, we expect other revelations. In the meantime, here are 10 things we’ve learned.

1. There is broad interest in gaming in anthropology, one that reflects a long history of games in the discipline. Games and anthropology go back as far as the nineteenth century. All our workshops were well attended, as were subsequent game sessions. Moreover, holding these events introduced us to people in anthropology already involved in game studies in anthropology and incorporating gaming into their work.

2. Yet there is also resistance to gaming as a form of anthropological dissemination. Despite this history of games in anthropology, there is still little support for game design in academic anthropology (and, for that matter, games studies in anthropology). Each iteration of AnthropologyCon has been sponsored by the Society for Visual Anthropology, and has piggybacked on other experimental initiatives, including Ethnographic Terminalia and Wakanda University.

3. Game design in anthropology is not gamification. Gamification, in games scholar Ian Bogost’s infamous turn of phrase, “is bullshit.” To “gamify” something is to treat it as if it is not already a game. Much of the work anthropologists do, from research design to course design, is already a type of game, a goal-based modulation of experience through the use of rules. Further, Bogost points out that the -ification suffix “makes applying that medium to any given purpose seem facile and automatic.”. This approach leads to superficially slapping simplistic, easily reproducible game concepts like points and leaderboards onto a thing without taking seriously the ways that playfulness and gamefulness might offer means for more radically transforming anthropology by making visible and challenging otherwise unspoken rules.

4. Games offer participatory opportunities. We live in a golden age of game design, with indie games available in countless forms at the overlap of art, literature, politics, history, and anthropology. Yet what makes games so very different from other multimodal anthropologies is the play itself. Games are designed to be played. At their core, they are participatory in a way that other forms of anthropological dissemination are not. It’s often just the opposite, with the scholarly journal article or monograph serving to close off participation. This is especially true when utilizing gaming in curriculum design. We have numerous exercises now on gaming anthropological theory and even ethics through Cards Against Anthropology, a game kit that has been translated into several languages globally. Not only do students respond positively to exploring anthropological theory and methods through games, but games become a way to explore these ideas through a collaborative method where students design games themselves.

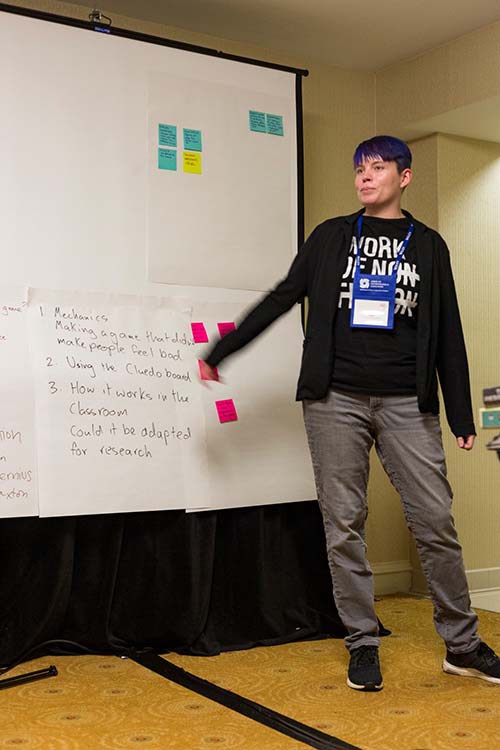

5. Game design can be a collaborative methodology. Our games workshops involve people coming together to design together. This models an ideal relationship between game design and game play. To the extent that design is collaborative, games become more than the sum of their mechanics―they are the products of complex negotiation that are the practice of the group. As in other forms of collaborative anthropology, the process itself is an important outcome, one that can be both revelatory of ethnographic truths and productive of community.

6. Ludic is not the opposite of serious. Games can be both. A sharp growth in so-called serious games (think Alex Rowland’s Canned or the Urban Ministries of Durham’s Spent) show that difficult, complex situations can be approached in different, critical ways through gameplay. Games can also be political. The game Thoughts and Prayers makes the rounds of social media every time there is a mass shooting and highlights the empty rhetoric of politicians and others who use that phrase to express empathy that rings hollow.

7. Anyone can design a game. Yes, there are courses and (increasingly) departments in game design. But much like other media, there’s not a steep curve to designing a game, although it may take a lifetime to design a game well. A great repository for games designed by individuals is through the software Twine that has a download and thousands of examples of self-designed games, often very personal in nature.

8. You can use simple mechanics but not be reductive. Although there are maddeningly complex games out there, games can produce meaningful and even moving gameplay with simple mechanics. See Nick’s “Game Design Worksheet” from our second AnthropologyCon workshop, where he guides designers through a “Game Theme,” “Problem Statement,” and “Core Mechanic,” allowing even complex ideas to be modeled in an approachable way.

9. Games can be a powerful, reflexive tool. The reductions in the design process itself confront anthropologists with many assumptions that may need to be questioned―competition, individualism, colonialism. For example, do you “win” by conquering? Or by acquiring more than other players? How many of these game elements extend from colonial legacies and settler capitalism? Monopoly anybody? Since game design involves a core dynamic that is, on some level, a reduction of social life, it focuses attention on the way that we are simply reproducing ethnocentric assumptions in games. How might we design alternatives that engage players in the process of questioning their assumptions?

10. We really don’t know what’s going to happen with anthropology and games. Like other forms of multimodality, games represent an emergent form in anthropology. We anticipate a growing adoption of game design, but it is unclear how that will change our teaching and research. You can find a short booklet with some of our original thoughts, games, and ideas through our AnthropologyCon website that could be a model for replication.

You’re in a Large Room―A Game of Ethnographic Exploration

This is a simple game based on a table-top RPG (Parsely) simulating early, ASCII-based computer games (think Zork). These early computer games typically described a space and the limited programming allowed players to interact with that space in limited ways, using a limited “syntax” (as we called it back then): “open door,” “pick up object,” “inventory.” In this table-top game, people will take turns describing a space they’ve all experienced in the style of these early computer games:

A. Everyone plays together, collaborating on their description.

B. One person needs to keep notes on the “inventory.”

C. Each person gets to describe a room (or space), and each room should have two objects and at least one, other door. In addition, rooms can require the use of an object.

D. The rooms will be based on experiences in those spaces or situations.

E. Objects should also reflect common elements of that space.

F. As the group picks up or discards objects, someone needs to update their inventory.

G. After the last person has described their room, the group should think about what they could do with the objects they’ve collected.

At the 2018 AnthropologyCon, we did this with the “anthropology department,” but we have also tried this game with churches, parks, neighborhoods, and other spaces. There’s frequently an element of critique to these descriptions.