Article begins

In 2021, I attended a tour to Utøya with young adult Norwegian students on the ten-year anniversary of the terrorist attack there on July 22, 2011, and a subsequent Lutheran service held on their folk high school campus later that evening. The attack, perpetrated by a right-wing domestic terrorist on the Norwegian Labor Party youth wing’s summer camp, resulted in the deaths of 69 people, many of whom were between the ages of 18 and 20, the same age as most of the students with whom I toured the island.

Over the course of the day, values like trust, equality, and respect were invoked in a range of ways, both in the activities at the secular Utøya memorial center and in the Lutheran folk high school service back on campus. Christianity emerged in these activities, as students processed the role religious extremism played in the antidemocratic rhetoric associated with the July 22 attack and engaged in a different version of Christian practice on campus that promoted democracy by encouraging students to see each other as equals “through God’s eyes.”

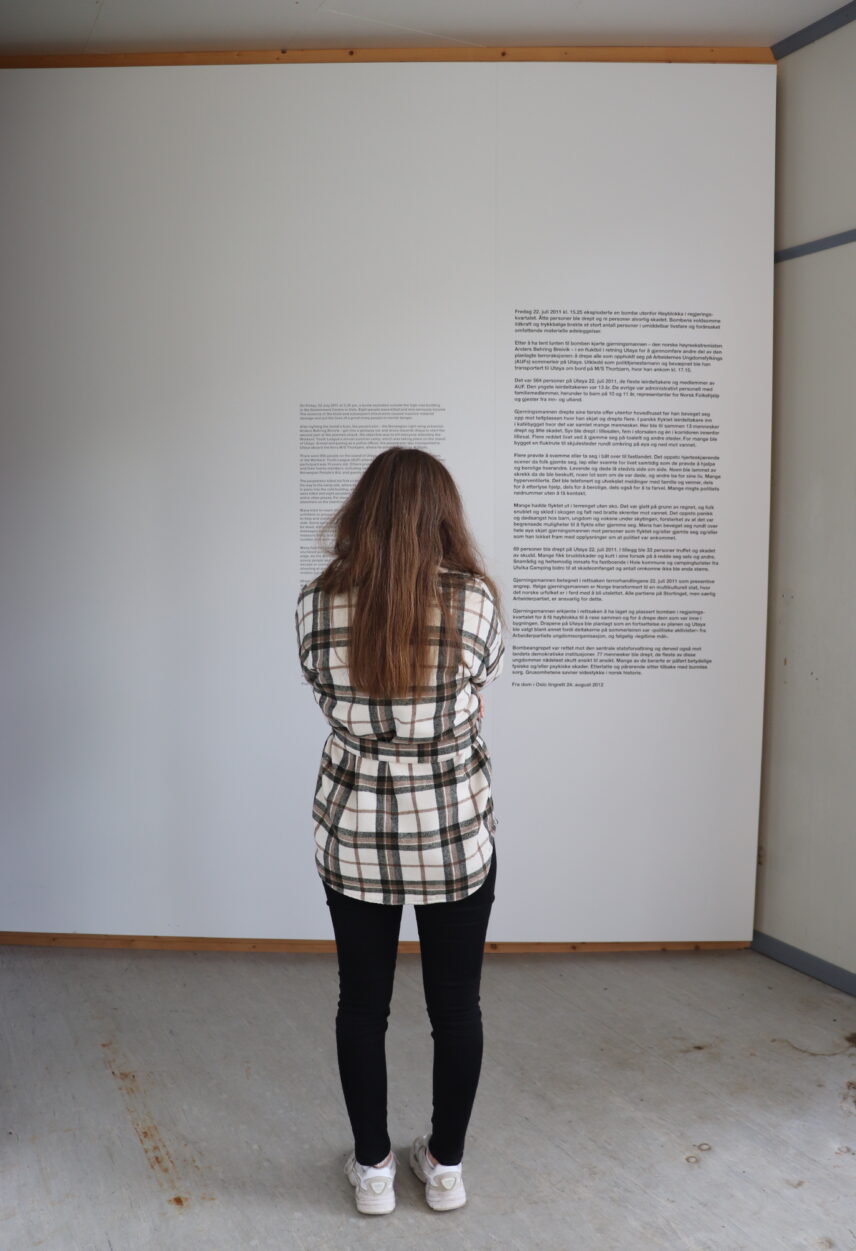

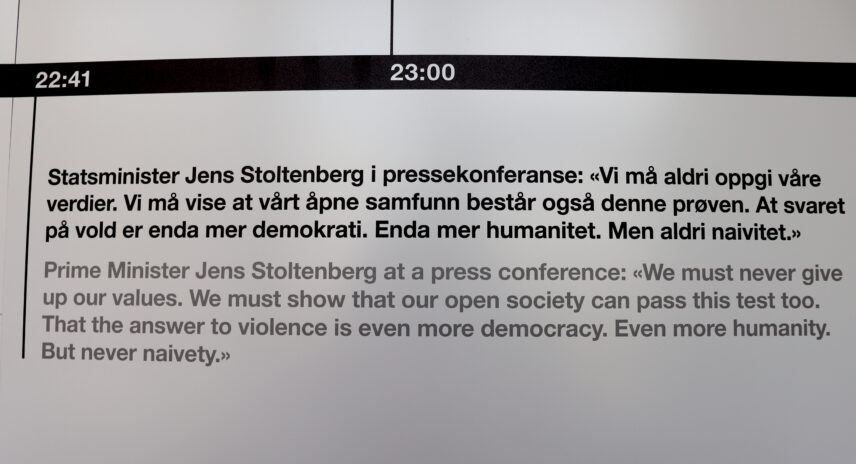

The trip to Utøya was organized by folk high school staff to give students an affective experience of the July 22 tragedy that they had witnessed on television as children, and to also teach them that social values like equality, respect, and safety could only be made possible through their active participation in contributing to the future of Norway’s democracy. These values were most visible on the signage in Utøya’s largest exhibition in Hegnhuset (The Safehouse), a memorial and learning center, where the events of July 22 were detailed in a timeline that wrapped around the interior of the room and included an excerpt from a speech Jens Stoltenberg, Norway’s prime minister at the time, delivered the evening of the attack.

In an address he gave on the ten-year anniversary of the massacre, Stoltenberg, now NATO’s secretary general, said that while the perpetrator had “misused Christian symbols,” he still “believed in the same God […] as the majority in this country.” Despite these signifiers of Norwegian belonging, Stoltenberg stated that the perpetrator was “not one of us” because he lacked respect for democracy. “Our most powerful weapon is our values,” he said. “Trust in democracy [and] trust in each other.”

The relationship among Christianity, trust, and democracy was reinforced during the Lutheran service students were invited to attend when we returned to campus after the tour. During his message, the school priest asked students to consider the following question: “How can we create a society where we trust each other?” He suggested that students could develop trust by exploring a version of democracy that was built on how God saw them as equals irrespective of their beliefs, bodies, or sexual identities. By lighting candles and writing prayer notes on behalf of each other, or those directly impacted by the events of July 22, students were invited to adopt God’s perspective in an effort to promote democracy in their school community. During these rituals, the interiority of students’ personal beliefs was subordinated for the sake of a collective, visible form of democratic belonging established “through God’s eyes,” a message that reflected Stoltenberg’s assertion that Norwegians’ most “powerful weapon” against extremism was their sense of trust in each other despite difference, religious or otherwise.

Through the events I photographed on the day of our tour, the message was made clear that to avoid another national tragedy like July 22, students would have to develop trust in their fellow Norwegians, which could be imagined by seeing each other as “God sees them,” through the eyes of a God who values democracy over dogma and belonging over belief.