Article begins

In Toronto, calls for inclusivity and diversity in sexual health care services abound, marking a paradigmatic shift from earlier forms of sexual health care in the interwar and postwar periods, where public sexual health services existed primarily to prevent the spread of venereal diseases across the country.

Many of the former members of Toronto’s Women’s Liberation Movement, who fought for the 1969 legalization of abortion and homosexuality, work within Toronto’s public sexual health care system today. They aim to make sexual health care possible in a space that is safe for all. But what makes a space safe, and how must actors actively maintain these spaces? In particular, how do Toronto’s sexual health care workers’ aspirations to inclusivity and diversity run up against the relations of power that constitute these spaces and their subjects?

For Theresa, who has been working in and around sexual health clinics in Toronto for over 30 years, making those seeking sexual health care feel comfortable is an important component of health care provision. This work includes ensuring the presence of non-English pamphlets and posters in the clinic’s waiting room, Theresa explained. Comfort was a value echoed by other health care workers including Pauline, a manager of another clinic.

Pamphlet series found in a waiting room of a Toronto sexual health clinic. Morganne Blais-McPherson.

The value placed on inclusivity and diversity was reflected in the pamphlets and posters that adorned walls and bookshelves in the waiting room at Pauline’s clinic. For example, the pamphlet series Loves Me, Loves Me Not is divided into sets with covers that target specific LGBTQIA+ identities, however, the information offered is identical.

Although sexual health care workers aimed for an affect of comfort in their respective waiting rooms, the rooms were curated differently. Theresa’s clinic, located in one of Toronto’s younger, lower-income wards that has a relatively high presence of people of color (demographics that over-represent the wards in which Toronto’s sexual health clinics are located), clients are greeted by a room of worn-out teal upholstery and a handful of washed-out posters. The clinic shared its waiting room with dental and oral health services, and the demure paraphernalia, Theresa explained, was a way of recognizing the sharedness of this space. The waiting room of the clinic that Pauline manages, located downtown and full of university students, young professionals, and other long-term residents of the community, was busier. The waiting room was enclosed in a room separate from the comings and goings of the building. This clinic was historically oriented to servicing Toronto’s LGBTQIA+ community, and hanging on the walls were posters presenting the social justice politics of the clinic. From posters declaring that “sex work is real work” to those advertising social groups for Black gay men over 30, this was intended to be a safe space in the broadest sense.

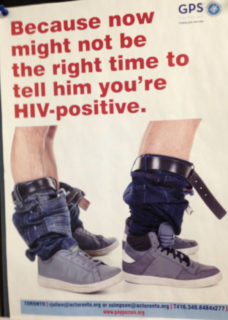

And yet, not everything goes in Pauline’s waiting room. One poster, in particular, depicting two pairs of legs, one set behind another, belt buckles undone, jeans down to the ankles, elicited unease for Pauline. Above this suggestive image was a message from the AIDS Committee of Toronto, “Because now might not be the right time to tell him you’re HIV-positive.” The poster was displayed in both the waiting room and in the consultation room; however, in Pauline’s opinion, the former of the two needed to be removed as it was “too public” to be anywhere else but in the confines of the consultation room. The message, suggesting that men-who-have-sex-with-men are—or could be—HIV-positive, was inappropriate in a public space like the waiting room.

What does it mean to have a space in a sexual health clinic be deemed too public? Why would such a poster be appropriate in the intimate spaces of the clinic, but not in a waiting room? Moreover, the waiting room had plenty of other posters about infectious diseases, HIV/AIDS, LGBTQ+ relations, and sexually explicit pamphlets. So, why this specific image?

“Too public.” Nicholas R. Abrams

In our research with sexual health care workers, it became evident that the clinical encounter was imagined by workers as occurring in separate spaces. One space, the waiting room, was coded as public and the other, the consultation room, was coded as private. Importantly, this spatial coding is not just imagined, rather, we argue that these spatialized codes structure the forms of care that patients are meant to experience.

For example, Theresa discusses her work in the consultation room as one of informing the clients and of “playing the devil’s advocate.” Her work involves, on the one hand, informing “[her] girls” of her hierarchy of birth control methods. She explains that given the right person, the pill is the best option as it gives the woman some control over her body and comes with reduced risk of many cancers, sexually transmitted infections, and pain related to the menstrual cycle. But this advice is also tailored to the individual sitting in the consultation room. A 35-year-old sedentary woman who “weighs 400 pounds [and] smokes a pack [of cigarettes] a day” would be met with something along the lines of, “Oh no dear, I don’t think we’ll be talking about the pill today.” But, Theresa cautions, the woman must also make this decision herself, without any pressure from her boyfriend. Theresa’s job at the clinic is to “massage [the] preconceived notions” the woman may hold, no matter where they come from. In addition to the profile of a “healthy” body, the pill requires certain behaviors. Theresa states clearly, “if you think you can commit to taking birth control every day at the same time, that would probably be your best bet”.

The public waiting room is marked by a lack of foreclosure, nothing is off-limits or disallowed and everything is permitted, being left to the expert patient’s authority. The consultation room, however, is imagined by health care practitioners as a place where uncertainty is refined. The health care workers’ intervention into what is usually regarded as a private matter—family planning and the ways in which one manages knowledge about their HIV/AIDS status—puts into question the idea of the liberal state that allows its subjects to do as they please in the bedroom. Following this spatialization of the clinical encounter from the waiting room to the consultation room, the distinction between a space coded as private and one as public, and the sociality of the public and the private, are muddled. It is in the privacy of the consultation room that one’s obligations to the body politic are most obviously made apparent—the safeness of the consultation room is always for the species body as well, the body whose inner mechanics are studied and intervened upon to optimize both life and nation. Insofar as these clinics are imagined, perceived, and aspired to by health care workers as being safe spaces, this safeness is troubled by the nature of the very spatialized modes of care through which health care in Toronto’s sexual health clinics are organized.

Morganne Blais-McPherson is a PhD student in the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, Davis. Her research is primarily based in Tuscany, Italy, where she works alongside actors in and around the fashion industry.

Nicholas R. Abrams is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Toronto. He primarily conducts research in South Africa where his interests include health, gender, and religious populism.

Please send your comments and ideas for SMA section news columns to contributing editors Dori Beeler ([email protected]) or Laura Meek ([email protected]).

Cite as: Blais-McPherson, Morganne and Nicholas R. Abrams. 2019. “The Clinical Importance of Space in Sexual Health.” Anthropology News website, November 18, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1318