Article begins

Sugar Land is a growing, white, politically conservative, suburb of Southwest Houston, Texas. It is home to one of the most sought after public high schools in the nation and proudly boasts itself to be one of the fastest growing cities in Texas with an increasingly multicultural population. The dominant historical narrative of this town is one of settlers such as Stephen F. Austin, William Jefferson Kyle, Benjamin Franklin Terry, and Edward Hall Cunningham. Until recently, the only historical record the city had officially recognized before its 1959 incorporation is a swift tale of Stephen F. Austin securing land from Mexico, Kyle and Terry naming the city after the source of their economic success, and Cunningham eventually creating a sugar mill that would employ thousands of Black prison laborers—a detail the city website does not quite emphasize. These narratives of white settlers are celebrated in schools, students participate in the annual “Colonial Day” celebration, and sugar has come to be a proud symbol referencing what current residents of Sugar Land call living the “sweet life.”

The discovery in 2018 of the remains of 95 Black prisoners aged 14–70 who were leased as part of the Imperial State Prison Farm to work sugar plantations has rattled Sugar Land’s notion of self. A racial history left unmarked, uncelebrated, and unremembered, unearthed itself in the midst of the city’s attempt at further educational expansion. The remains of the prisoners collectively known as the Sugar Land 95 were found when the local school district began construction in an open field located near the now inoperative Imperial Sugar Factory. The plan to erect the James Reese Career and Technical Center, a new technical educational facility for Fort Bend Independent School District (FBISD), was halted and the debate about the remains began (FBISD 2020). The prisoners’ unearthing evidenced a more complex racial history and identity than Sugar Land was prepared to deal with. For this is a town that still teaches high school students that slaves were “workers” and nonlandowner whites were equally oppressed by “the peculiar institution” (see Kennedy and Cohen 2015; Reed 2013). This pseudohistorical celebration of colonial whiteness shapes not only the way this city sees itself, it also shapes the ways in which Sugar Land understands Blackness and Black people. The sweet life is, in part, a multicultural dream of suburban comfort and community, seemingly being offered also to nonwhite residents of Sugar Land, but with one stipulation. The only pre-incorporation memory of self this town and its residents are to have are of the sugar itself, the pure “white gold” on which fortunes were made; not the Black labor, Black pain, Black death, and Black people that made that sweetness possible.

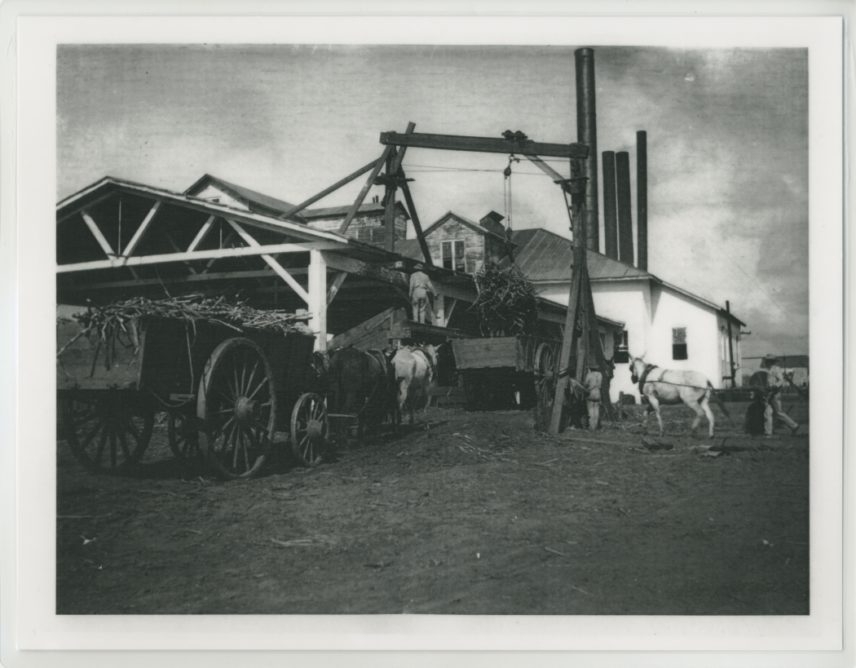

Who were these 95 people? The Sugar Land 95 were 94 Black men and boys and one woman who were leased to local plantation owners after the Civil War ended. Sugarcane had long been the primary cash crop of Fort Bend County, but it proved to be less economically beneficial without free labor (Clark et al. 2020). These laborers had previously been enslaved in the area and were recently incarcerated in the Huntsville Penitentiary where they were leased out to work long and brutal hours on the sugar plantations and in the sugar factory. Like many other leased convicts at this time they were often charged with violations of black codes, designed to counterbalance the 13th Amendment (Coates 2015; Perkinson 2010). Forensic archaeological research of the remains has disclosed the violence, exhaustion, and poor health they experienced, including broken bones, gunshot wounds, and evidence of genetic disability (Clark et al. 2020). Researchers also excavated old chains, metal collars, and broken tools indicating the bondage and drudgery that filled the laborers’ lives (ibid.). There was nothing sweet about their experience in Sugar Land, Texas, just a sour nightmare of labor exploitation and death.

Sugar Land has been under national pressure over the last two years to vindicate these lost individuals through a proper memorial and museum that would narrate the identities and oppressive contexts of these mostly young Black lives and deaths (CLLP 2020). I was asked to sit on a committee of Sugar Land residents and scholars with whom the city and the school district were initially open to collaborating in designing their response. Historians, archaeologists, anthropologists, parents, and museum administrators met with FBISD lawyers and cultural liaisons to decide, first, if the remains should be moved. Where would they go? How would the city respond publicly? The committee was soon dismantled once FBISD realized that most members wanted the remains to stay where they were found, for a museum to be built near them, and for the educational facility that was planned for that space to be moved elsewhere. Moving the facility was not economically favorable for the school district. Subsequently, there were heated exchanges, legal injunctions, and protests by The National Black United Front, activist Reginald Moore and The Texas Slave Descendants Society, and the Sugar Land Heritage Foundation who all fought to either memorialize in-place or to reinter the 95 bodies. The debate was about so much more than the geographical location of the remains. It seemed that FBISD and local Sugar Land officials wanted to filter out historical impurities that challenged the pristine whiteness of their imagined post-incorporation history—a sweeter history based on anti-Black lies.

Reginald Moore advocated on behalf of the Sugar Land 95 from 1999. He publicly warned the city and the school district that there was an unmarked cemetery somewhere in the area, a fact he learned of while serving as a prison guard at the Jester State Prison Farm (Hardy 2020). Moore had long understood that the real historical narrative of Sugar Land is not one of sugar refinement, economic boom, and sweet suburban comfort. Moore always maintained that Sugar Land and Fort Bend County had been built on the backs of leased Black convicts. Even with the support of the history department at Rice University, he was still ignored by officials from the city and the school district (Landry and Perez 2020; Moore 2018). Not until the builders working on behalf of FBISD literally dug up remains, did everyone stop to listen. Sadly, that momentary pause was quickly eclipsed by economic greed and complacence with the silencing of Black narratives of pain that seems to come easily to this town. These Black lives that Moore and others sought to commemorate shifted Sugar Land’s understanding of self from a neutral sacchariferous reality to a dark hidden underbelly of exploitation, torture, and death. Sugar Land officials and cultural heritage workers struggled to figure out how to deal with this “new” history that threatened to decay the fantasy of the sweet life that so much place making had been built on.

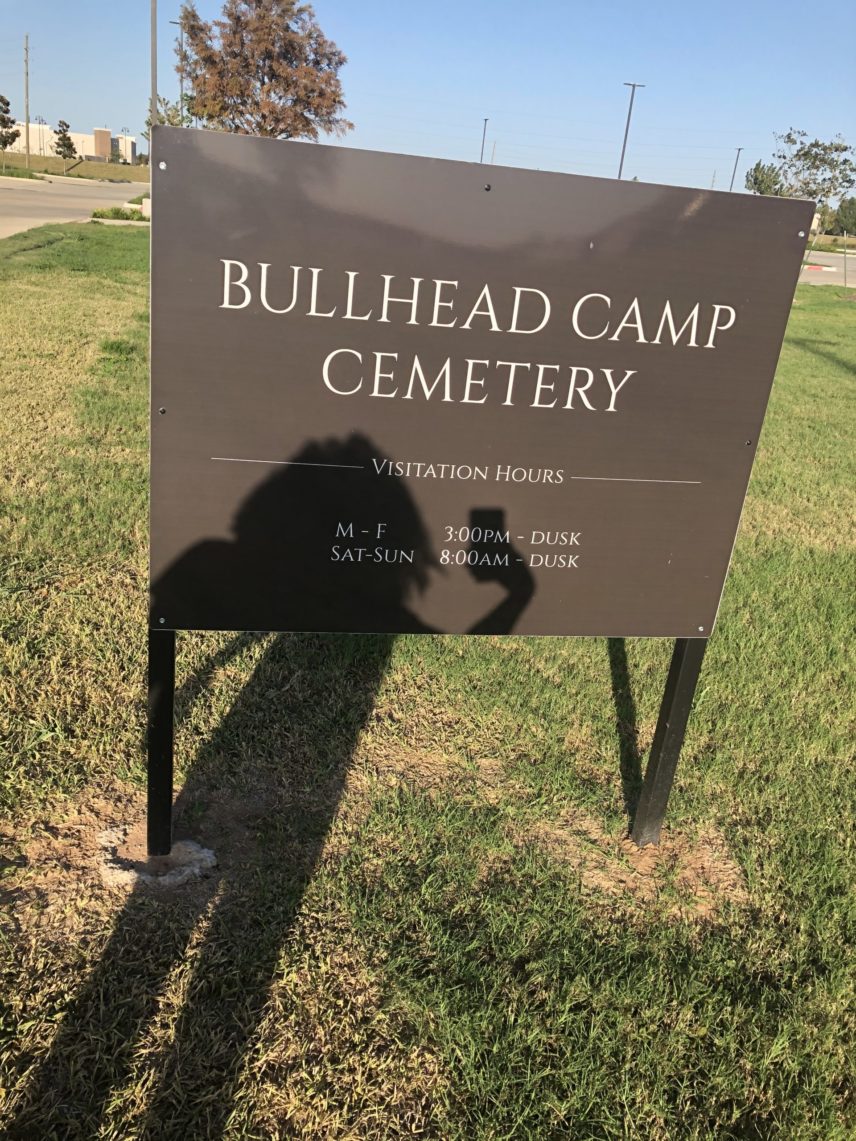

In late 2018, FBISD officials decided that the Sugar Land 95 would be reinterred and honored in the Old Imperial Farm Cemetery, a multiracial cemetery that commemorates prisoners and prison guards who died between 1912 and 1942 at the Texas Department of Corrections’s Central Prison Unit. Placing these bodies in a cemetery that is not clearly linked to a narrative of slave labor, mass incarceration, and anti-Blackness further ignores the historical trauma Sugar Land’s beginnings are responsible for and dependent upon. A cemetery that celebrates fallen white prison guards is perhaps another cultural attempt at leveling historical Black injury and white oppression, a typical FBISD offense that I have shown to manifest in the historical curricula often adopted by this school district (Reed 2013). If these bodies had been buried together so would the distinct historical contexts of racial violence that overwhelmingly shaped the lives and deaths of the Black Sugar Land 95. Reginald Moore, along with numerous other activists and experts, pushed back against this decision and after numerous legal battles and conflicts it was decided by all that the Sugar Land 95 would be laid to rest in the exact same spot that they were found, an area now called the Bullhead Camp Cemetery. The truth, no longer sugarcoated, is being told and honored in a more genuine way that perhaps brings Sugar Land a little bit closer to its sweet self-image.

The city’s official website now includes an updated historical timeline with several frames that feature images and narratives spanning from slavery to convict leasing and labor exploitation. On a separate part of the website there is a page dedicated to explaining who the Sugar Land 95 are, their path to their final resting place in the Old Bullhead Cemetery, and where they were originally found. But Sugar Land, like the rest of the United States, is in the midst of a new era. This website and these commemoration decisions did not happen overnight; it was not until Reginald Moore’s passing in June 2020 and the national awakening to anti-Black racism in response to the brutal murder of George Floyd that these anti-racist, social justice changes were made. The Bullhead Cemetery has allowed the remains to be unmoved and the location in which they were found to be preserved, but the markings and surroundings of the cemetery leave much to be desired (CLLP 2020). There is very little historical information at the site and the graphite grave markers all read “unknown” with an identifying number. In some ways FBISD is continuing to eclipse representations of historical Black oppression as the cemetery sits in the shadow of the now complete technical educational facility that swallows the area. One would have to park in the back of the school to even catch a glimpse of the 95 dirt graves that now fertilize the soil of the fields that once bore sugarcane.

Sugar Land, like so many other suburbs in the American South, has always wanted the sugar in their history without the labor and the pain of that particular type of economic past in their immediate memory of self. There are a few critically inclusive examples of museums and plantation memorials that make central to their narrative of sugar the Black pain and labor and life and death that was required to process that particular crop. Both The National Museum of African American History and Culture and The Whitney Plantation narrate the history of sugar in the United States and Louisiana respectively through cultural objects and oral histories of Black experiences. So that a trip to one of these places leaves visitors with imagery of bodily burns from boiling sugarcane and broken backs from carrying flaming hot and unbearably heavy cauldrons. These types of humanizing and necessary details of the experiences of the Sugar Land 95 are not so clear, not on the Sugar Land website, nor in any educational tools currently available to Sugar Land residents and students.

As an anthropologist I recognize that the school district’s effacing of Blackness in textbooks and now in city memorials and monuments mirrors much of the traditional social scientific and historical treatment of Black people. More specifically, Black bodies have always served as the superficial “other” whose identity is manipulated and erased as needed in order to create a particular white western self, a tradition that textbook writers and perhaps facilitators of the Sugar Land Heritage Foundation are potentially carrying on even as anthropology has begun to attempt to self-examine and self-correct. In fact, there is no epistemological precedent for understanding Black identity as foundational or residential in Sugar Land. This is a city that consistently redefines itself as white, not only in the absence of acknowledging any real Black history, but also in opposition to its neighboring predominantly Black city, Missouri City—consequently home to many of the Black and Latinx students who will be filtered into the technical school that was to stand where the Sugar Land 95 now lay. Discovering that Black bodies built the sugar economy of this town and have historical and consequently cultural and familial claim to Sugar Land and its forefathers not only angers me and other Black residents of Sugar Land and Missouri City, but also puts pressure on city officials to do more than commemorate. Currently there are efforts in motion to conduct DNA testing of the Sugar Land 95, as officials seek to create some reparative response. The hope now is that these efforts and the path to their implementation will be sweeter for the descendants of the Sugar Land 95 than the treatment that these Black founder-laborers of Sugar Land received.