Article begins

“I Can’t Breathe.” The last words Eric Garner uttered on a New York City sidewalk in 2014 were also uttered by George Floyd in 2020. Through the years, these words link the deaths of far too many Black people in the United States and across the world due to violent encounters with state agents including the police. In the midst of the COVID-19 global pandemic, disproportionately borne by Black people, these three words have even deeper resonance: they provoke grief and mourning; they urge action; they invoke restorative practices among Black people to mediate repression; and they beseech us, as anthropologists, to investigate racial inequities in the access to breath, the essence of life itself.

Black breath illuminates the social, political and, above all, bodily vulnerability of Black people. The concept also affirms the significance and sanctity of Black lives and Black bodies especially given the perilous convergences of police violence, the global pandemic, and racial inequities.

The insights presented here build on my prior work investigating political performances in Johannesburg, South Africa, where I focused on protest singing and collective mobilization with implications for breath. I also draw from my experience as a yoga instructor, certified breathwork teacher, ashtanga practitioner, and founder of a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting Black and other marginalized communities through breathwork and healing justice modalities.

Respiration transcends race and species. Yet blackness, being an embodied experience of racial dynamics, confronts breath directly. As the late South African musician Sathima Bea Benjamin described it, “Black is not a color, it’s an experience. And in South Africa, there are only two possible experiences. I was never privileged to know what the white one was. That makes me black.” Benjamin’s words foreground experiences of inequities as graspable in a bifurcated dynamic that observes whiteness as an unremarked category, enabled by the casting of blackness as a negative catch-all for all that whiteness, in its privilege, disclaims.

Blackness illuminates social inequity that is specific but not limited to Black African descendants. Similarly, breath has the potential to be a connective force drawing together multiple points of exposure and vulnerability specific to Black experiences, and also marginalization and bodily precarity among those not racialized as Black.

While police brutality and vigilante targeting have raised public awareness about racialized respiratory repression, Black breath has been historically compromised for centuries through the exploitation of Black people as disposable consumers, workers, residents, migrants, and citizens. Economic disposability and political neglect rendered predominantly Black neighborhoods around the world disproportionately polluted and vulnerable to natural and unnatural disasters. Black individuals and communities have disproportionately been subjected to bodily exposures that constrict their breath.

Black lungs

One illuminating example of such exposure is offered by the United States’ tobacco industry. From the 1940s onward, spurred by the Great Migration and increasing numbers of Black folks settling in northern cities and urban areas in the South, the tobacco industry cast Black consumers as a distinct market. Alongside cigarettes, especially mentholated cigarettes, malt liquors, cheap whiskies, fortified wines, and specialty items including hair products flooded impoverished Black communities across US cities.

Using a three-pronged approach of targeted marketing, progressive hiring practices, and philanthropy, the industry worked, according to social behavioral scientists Valerie Yerger and Ruth E Malone, “to increase African American tobacco use, to use African Americans as a frontline force to defend industry policy positions, and to defuse tobacco control efforts.” In the 1950s, as the civil rights movement was gaining momentum, the tobacco industry was ahead of the curve. Philip Morris and others were among the first to hire and promote Black employees into executive roles. Progressive hiring practices and extensive charitable contributions to Black cultural, educational, and political organizations entrenched affiliative attachment to the industry in African American organizations and communities.

These “progressive” efforts constricted Black breath, contaminated air quality in Black communities, and reduced the longevity of Black lives. Black Americans are more likely to die from smoking-related illness, including from various cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and respiratory ailments than whites. At least 47,000 Black people die each year in the United States from smoking-related illness, making tobacco the greatest preventable cause of death for Black people in the country. Tobacco kills more Black folks than car crashes, HIV/AIDS, murders, and drug and alcohol abuse combined. Black children and adults are more likely to be exposed to second-hand smoke and its deleterious effects than any other racial or ethnic group in the country. By targeting Black citizens as consumers of its toxic products, the tobacco industry practiced a politics of disposability, which adds historical resonance to current calls to affirm that #BlackLivesMatter and participate in a global Movement for Black Lives.

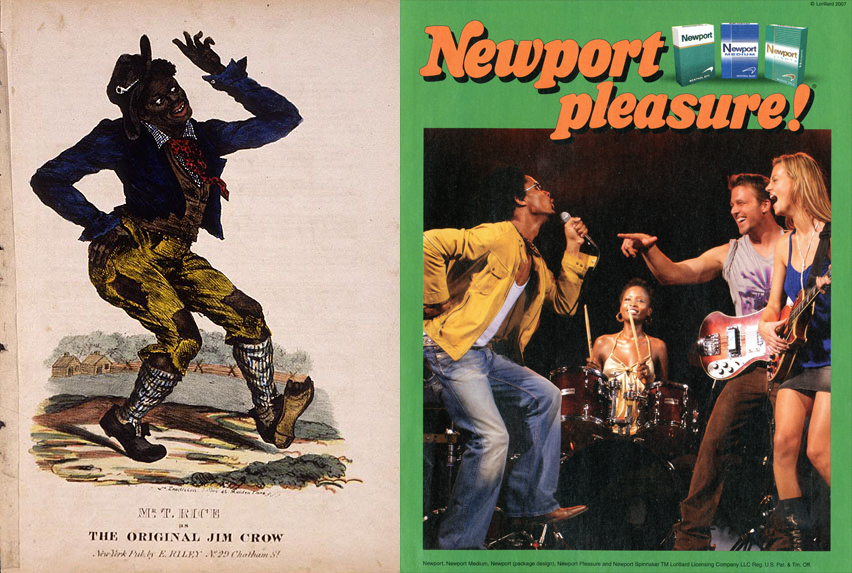

As manifest in the juxtaposition of Jim Crow minstrelsy with a 2007 Newport print ad, the tobacco industry’s exploitation of Black consumers follows longer histories of racism, slavery, and colonialism that treated Black bodies as contemptible and thereby disposable. For example, colonialism on the African continent profited from labor practices that restricted Black breath. Mining corporations in Southern Africa targeted Black men as disposable workers in labor conditions that rendered them more susceptible to black lung disease, tuberculosis, and other respiratory ailments. The disposability of miners—whose occupational exposure to silica dust, asbestos, and other toxins puts them at risk for these respiratory diseases—also played out among Appalachian mine workers in the United States. Black miners were part of a strong labor movement in Kentucky in the 1930s that fought back to achieve some protections, although they are now once again under threat.

Black breath

These histories become prologue to the inequitable health outcomes that we have seen amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a virus known to target the respiratory system. The disproportionate impact of the virus on Black, Latinx, and Indigenous bodies exposes not only racial disparities, implicit biases, and the systemic racism underpinning these inequities in our health care system, but also the politics of disposability at play in the Trump administration’s calculations regarding the virus. Despite warnings from public health officials, many state governments reopened businesses and loosened lockdown restrictions in April and May 2020, leading to a resurgence of infections in communities of color.

Breath also connects the COVID-19 pandemic to other instances of harm, including police brutality. The same communities that are more vulnerable to the pandemic are more vulnerable to premature death from police and extrajudicial violence. The words “I can’t breathe,” linking the deaths of Eric Garner, George Floyd, and Kayla Moore, among countless others, have drawn public attention to chokeholds and other methods of police restraint that physically restrict our most basic need for air. Defined by the New York Police Department (NYPD) patrol guide as “any pressure to the throat, carotid artery or windpipe, which may prevent or hinder breathing, or reduce intake of air or blood flow,” chokeholds have been prohibited by the NYPD since 1993 but remain in use by NYPD officers—an indication of the disposability of particular communities. The same patrol guide lists “sitting, kneeling, or standing on the chest or back of a subject in a manner that compresses the diaphragm, thereby reducing the subject’s ability to breathe” under prohibited methods of restraint. Perhaps there’s no greater indication of breath as a binding link of Black exposure than the revelation in an autopsy report that George Floyd, who died with his neck under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer, tested positive for COVID-19.

Black breath and recovery

While the concept can be used to trace multiple points of exposure to harm, Black breath is not without hope as it can be mobilized to investigate practices of repair, recovery, and restoration in African-descended communities across the world.

Among isiZulu speaking shack dwellers in Durban, South Africa, “ukubhodla” (coughing out) is key to mediating the tension of not being able to breathe in an industrially polluted urban periphery. As anthropologist Kerry Chance notes in Living Politics in South Africa’s Urban Shacklands, “Coughing out is when you clear your lungs of pollution to breathe—whether to sing, pray, or speak—in [collective] ritual space” (2018, 64). Ukubhodla is a mode of curative purgation that relieves discomfort by dislodging and expelling polluting particulates; it asserts presence by breaking through stifling air with sound, allowing the persons coughing out to be heard and felt by others. The production of sound itself, whether through song or speech, involves the management of breath—a skill that can be cultivated to varying levels of expertise—and transverses bodily interiors and exteriors. The quality of sound, viscerally experienced, along with subjective and intersubjective sonic associations affect not only the speaker or singer, but also hearers. Ukubhodla therefore facilitates connection and solidarity during collective events by allowing residents besieged in urban peripheries to momentarily change their bodies by expelling pollutants even as they change the air and link with one another through sound.

Like water, which, as the illustrious Afrobeat singer Fela Kuti has noted, abides no enemy, breath is a point of exposure to harm and a salve. In African-descended communities worldwide, breath mediates grief, mourning, collective queries, demands for justice, the cultivation of ancestral relations, and other responses among survivors confronted with lost lives and denied breaths. In isiXhosa, which along with isiZulu is among South Africa’s 11 official languages, ukuphefumla is a verb meaning to breathe. Umphefumlo, its noun derivative, refers not only to an individual’s breath but also their spirit or soul. Umphefumlo links an act that sustains life to a phenomenon as invisible, intangible, and intractable as one’s spirit or soul. Umphefumlo indexes not only the body as an abode for the physical management of air but also a nonphysical spiritual realm anchored to but also existing beyond the material body. IsiXhosa is not alone in this connection that manifests even in contemporary English: at the root of respiration or inspiration is the Latin spiritus, meaning “breath, spirit,” from spirare “breathe.” Umphefumlo not only recognizes this link, it embeds it in collective action.

Much like ukubhodla (coughing out) mediates industrial suffocation in urban peripheries, ukuphefumla (breathing) during mourning mediates the weight of grief. As Allen Feldman points out regarding the connotations of breath in a South African context of loss,

A person in mourning, a person harboring great suffering and emotional stress, experiences a heavy weight on the chest and shoulders, and cannot breathe easily […] To breathe is also to speak of painful events that weigh on someone […] This speech is the exhaling of the soul, the release of blockage, and an emergence from social death” (2004, 177).

While the dead may have died in isolation due to racialized state-sanctioned and extralegal violence, the breaths of those who mourn them pour forth in wails, songs, and speech to reclaim them from the grips of violence and socially reincorporate them into communities of shared feeling that cross national boundaries. Christen Smith examines parallel mediations regarding the role breath in the justice-seeking work of grief in Bahia, Brazil, thus locating such moments not as evidence of Brazilian or South African exceptionalism but as part of a Black diasporic experience.

The tobacco industry’s exploitation of Black consumers follows longer histories of racism, slavery, and colonialism that treated Black bodies as contemptible and thereby disposable.

If breath shapes the body through the physical exchange of air, it also indexes an ineffable realm of spirit and soul. Breath expands and deflates the lungs with air even as it emerges from and releases the soul.

Understanding breath as a force connecting the material and the ineffable highlights how Black people experience the convergences of racial violence, health and environmental hazards, socioeconomic precarity, and natural disaster through time and space. “I can’t breathe,” these immortal dying words are provocation not only toward grief and mourning but also to analytical rigor as part of anthropology’s contributions to the movement for Black life. In responding to these calls, Black breath as an analytical resource exposes deeply historical phenomena that link experiences across geopolitical and environmental climates due to enduring structures of power that order contemporary human life. Black breath draws us not only to explicate harm but also to investigate efforts to repair, recover from, and reclaim a world that has not been faithful to Black freedom by denying that most fundamental human need: breath.