Article begins

Bandung is a city of punks and prayer…

The cat is out of the bag now that Lonely Planet knows that Bandung, Indonesia, is a hot spot for punk rock. Over the years, I have discussed my research with different people from all over the world, and many are surprised that punk still exists. Punk is not dead; in fact, it is alive and thriving in the urban centers of Indonesia and has been for some time.

Image description: Three persons are on stage under blue lighting. Two are grabbing microphones and singing while the third with spiked hair is playing a guitar. One of the singers is holding a microphone stand with a white flag and writing that is not clear. In the background there is a fourth person playing a drum and in the foreground there are the backs of people attending the performance.

Caption: The band Reject (Bali) playing in Bandung. Resistance movements and punk often go hand-in-hand, the singer’s flag marks support for punks against ecological destruction in Bali. Steve Moog

If you are tuned in to the visual cues of punk, it is difficult to wander around Bandung, Jakarta, Denpasar, or any other major city in the country without seeing markers of the scene. Early in my fieldwork, I bumped into some teenagers in the Dago area of Bandung, and one of them was extremely excited that the band shirt I was wearing and the back patch on his jacket were both representing the same obscure punk band from Portland, Oregon. Indeed, the punks in Indonesia are numerous and, as the kid’s fandom exemplified, plugged into the broader global punk rock scene. While punk takes different forms in Indonesia today, I focus on Bandung’s anarcho-punk scene and the global connections they maintain that are predicated on do-it-yourself (DIY) or anarchist principles. This group is redrawing sociopolitical and cultural borders, which is particularly noteworthy in a post-authoritarian nation with an emerging democracy.

Bandung is a sprawling and densely populated city in West Java, situated approximately 90 miles southeast of Jakarta. The city proper has nearly three million inhabitants, while the metropolitan area has nine million residents. Physical remnants of Dutch colonialism in the form of broad boulevards and European architecture have earned the city the moniker “Paris of Java.” Bisected by the Cikapundung River, Bandung sits in a valley surrounded by volcanic peaks. Like all cities in Indonesia, Bandung’s profound income inequalities are hard to miss; corrugated metal shacks bunched together form sprawling communities nestled up alongside opulent malls and high-rise buildings. Bandung is known as something of a college town, as it is home to several major universities, both secular and Islamic. This has attracted people from different backgrounds to Bandung creating a “hip” and cosmopolitan atmosphere against its abject poverty. The Bandung rock scene is embedded in this setting of striking juxtaposition of rich and poor. Although the city is associated with a rapidly evolving youth pop culture, the punk scene has been thriving for some time and well-known bands have been playing for over 20 years.

Anarchist punk does not exist in a vacuum, and punk’s lived realities are complicated by familial, financial, and social expectations. Band members have children and jobs and are situated in complex global power dynamics.

Not everyone in Bandung agrees on what punk actually is. The broader global punk scene also grapples with ambiguous definitions and lines of demarcation. There is a general acceptance, though, that punk is more than a music genre and is characterized by an adherence to DIY ethics. Even though DIY ethics are a central concept for contemporary punk rock, there is often little consensus as to what constitutes “doing-it-yourself.” At its most basic, DIY punk is an emphasis on cultural production that is independent of large-scale corporations or hypercapitalist agendas. However, interpretations vary greatly. I went to one DIY punk show which had a large stage, elaborate lighting setup, and an impressive sound system all backed by commercial (though not corporate) sponsors.

There are, however, groups within the Bandung punk scene that abide by a hardline interpretation of DIY; they understand it as practiced anarchism. Indeed, the anarchist punks (anarcho-punks) frame their interpretation of DIY on mutual aid, nonhierarchical organizational practices, and deep-seated anti-capitalist sentiments. To them, doing-it-yourself means doing-it-with-friends and doing-it-without-profiting. Whereas indie-company sponsored events fall within the realm of acceptable DIY practice, some anarcho-punks disagree.

At one particular punk anarchist collective that I work with extensively, I saw DIY employed as practiced anarchism and noted the implications for resisting pervasive power structures such as the state and global capitalism. Thinking about anarchist punk’s resistance may evoke images of bricks flying through Starbucks’ windows or clandestine missions to spray paint anarchy symbols in inappropriate places. However, in this collective, forms of resistance were enacted through seemingly mundane and routine interactions. Theorists of resistance have long noted the power of everyday acts to engender social change. At the collective where I worked, these acts included growing gardens and raising chickens and fish. As they see it, “Resistance is Fertile:” sustainability is conceptualized as an anti-capitalist act.

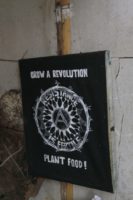

Image description: A black poster hangs on a partially painted wood wall. The poster includes white text that states “Grow a revolution” and “Plant food!” Between those two statements is a white circular design with an “A” in the middle, and text reading “resistance is fertile” circles the “A.”

Caption: Artwork at a punk collective in Bandung. Steve Moog

Although the implementation of DIY principles within the local scene presents ample opportunity to unpack small-scale hidden acts of resistance, the Bandung anarcho-punk scene is also plugged into and firmly a part of complex global DIY punk networks. Anarcho-punks in Bandung are not merely taking part in online-only communities or virtual worlds; instead, they participate in and facilitate transnational movement. Punk bands from North America, Europe, Australia, and all over Asia regularly pass through the DIY music venues in Bandung and other cities on Java and Bali. Less frequently, bands from Bandung play international gigs as far away as Europe. While an international tour sounds luxurious, this is the DIY anarcho-punk scene. Venues are sometimes dilapidated squats and bands are rarely paid for their performances—these gigs are not about promoting a new album or selling merchandise. These global networks rely on DIY or anarchist principles of mutuality and have created strong bonds between people in places far removed from one another. Although physically separated from punk hot spots in North America and Europe, the Bandung anarcho-punk scene is a critical node in global anarcho-punk networks and through their transnational connections and movements beginning to redraw cultural boundaries and relationships.

In keeping with anarchist traditions, the punks I worked with often conceptualize themselves in terms that circumvent geopolitics, nationalism, and socioeconomics in their chosen identities. From the anarcho-punks’ perspectives, it is more accurate to describe themselves as punks in Indonesia, rather than Indonesian punks. The small semantic distinction represents a larger opportunity for resistance as it acknowledges a level of dissociation from the state. However, the identity of anarchist punk does not exist in a vacuum, and punk’s lived realities are complicated by familial, financial, and social expectations. Band members have children and jobs and are situated in complex global power dynamics. While “Indonesian” may not be a prominent identity for anarcho-punks, it does not mean it is negligible. Interactions with capitalism, national identities, and broader power dynamics complicate resistance enacted through DIY or anarchist punk. These negotiations contribute to broader conversations regarding what it means to be Indonesian and impact ongoing nation building in an emergent democracy. It is messy and nonlinear—as daily acts of resistance always are.

Steve Moog is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Arkansas. His research addresses issues of resistance, translocality, and global networks through the context of Bandung’s punk scene in Indonesia.

Cite as: Moog, Steve. 2020. “The Everyday Resistance of Anarchist Punks in Bandung, Indonesia.” Anthropology News website, September 23, 2020. DOI: 10.14506/AN.1505