Article begins

This article is dedicated to the people of Charlottesville, peaceful assembly, and the fight against racism for which it stands.

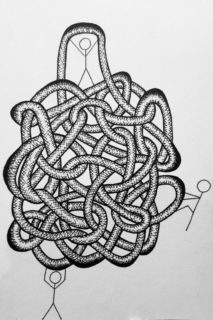

An all too familiar approach to the gordgantuan problem (a double articulation, referencing Gordian and gargantuan, to express, at once, difficulty and enormity) of racism in the United States has been the prodigious search for its ends, its reach, and its grasp. But what if the ends of racism, like those of the Gordian knot in Greek mythology (Burke 2006), are not only deeply buried but invisible, entrenched even, in layer upon layer of intricate and delicate tangles, of histories, and of social complexities?

The Gordian Knot. Artwork by Mandana Teheri Shemirani

The unlikely inspiration for this question is art, and of all things, a seventeenth-century piece of incidental music written by English Composer Henry Purcell to accompany the play “The Gordian Knot Untied” (Purcell 1691). Putting the myth to music provided audiences with an intriguing metaphor for grappling with complex social issues of the time. Here, I take up the metaphor of The Gordian Knot and introduce the development of a new form, what I term “explorations in incidental anthropology,” adapting the message of the myth to pursue an enduring concern of our time, racism. In places, the text that follows is intentionally tangled to index, metaphorically, at once a mood and the topic under consideration. Written like an ethnographic question, intended to be read aloud, and written to engage the reader in responding to racism in the United States, this work of incidental anthropology seeks to articulate the difficult work that lies ahead for each of us. In that spirit, the questions that it raises are opened but not ended.

The reflection that follow emerges at the nexus of creative processes and influences (ideas circulating from Greek mythology to classical music, dance, poetry, anthropology, politics, and philosophy). Its development, prompted by national moods, is reminiscent of earlier adaptations that illustrate the movement of ideas across disparate art forms and disciplines. Consider, for example, the early symbolism of French poet Stephane Mallarme’s L’après-midi d’un faune, whose work inspired Claude DeBussy’s composition of the orchestral piece, Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, music that stirred Vaslav Nijinsky to choreograph his ballet, L’Après-midi d’un faune. “Incidental anthropology” is an exploratory form and like incidental music, it is written to point to and accompany a mood or action. The goal, borrowing again from the arts, is not to exhaust its subject, innumerate details or produce a definitive account but instead to share a rendering, an accessible sensation, an impression of the lived world as seen, felt, and understood.

Though the topic deals with historical themes, the incidental form is by design apprehensive of convention and the seduction of attempts at summation. “History,” T.S. Eliot reminds us, “may be servitude, history may be freedom. See, now they vanish”(Eliot 2004). These sentiments were expressed much earlier by Paul Cezanne who noted that “artists use the history of art to free themselves from conventional forms of vision that interpose [intervene] and reproduce formulas rather than genuine vision”(Ferguson 2006, 35). The hope is that this rendering of racism in America, as incomplete as it is incompletable, might yet accompany growing national moods, calls and actions for justice and equality. In the cause of these efforts, this work expresses an abiding belief that sharing hope, particularly in the face of growing political despair, can help keep the collateral damage of our critical analyses in abeyance, what Romain Rolland famously warned was, “the pessimism of the intelligence which penetrates every illusion,” and help encourage us to rediscover again, in ourselves and in each other, the indominable “optimism of the will”(Fisher 2003, 88). In the midst of what seems to be a resurgence of public racism in the United States, we may do well to recall that not too long ago it was this optimism of the will, paired with the tools of time that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. demonstrated could “adjourn the councils of despair.” Now, it seems that they may be reconvening, and another generation must find that optimism of the will once again to address the problems of their time in their own voices.

“Herein lie buried many things,” the words that began W.E.B. Dubois’s immortal “Souls of Black Folks” published 1903, are mournfully not an epitaph, marking the grave of racism in America, where it lay dead (Dubois 1903). They are a haunting reminder of the remains of what remains hidden. For the field of anthropology, quadrifoliate and inquisitive, unearthing the strange stratigraphy of racism would require many things. It demands the deft hands and mixed methods of archaeologists to reconstruct and preserve; and the bioscientific and technological prowess of physical anthropologists to unweave, once and for all; biological evidence of our shared evolution, our origins. Untangling this gordgantuan knot requires the keen observations and disciplined participation of cultural anthropologists to document the innumerable tendrils of injustice and inequality reaching in and out of its production, and also the astute ear and accurate transcriptions of linguistic anthropologists to parse these unspeakable narratives and hear the unvoiced voices that hold the whole story of racism together while interactionally hard at work keeping us apart.

Could it be that a pursuit of the ends, of archiving the origins of racism, through whatever our lens, is liable to land us, as Eliot put it, no further than at “the end of an endless journey to end”? And to that end we might as well consider what has been the inconsiderable: ending the search, not for solutions to racism, our nation’s Gordian knot, but for its origins. In turn, we could turn our attention and energy to the means. It is perhaps through the means, the mechanisms, which are visible everywhere and nowhere that the hidden ends, the remains of racism, are not only indicated but also perpetuated.

The answer is not to call for an ahistorical turn but a realization that “the question of the archive,” and the act of archiving as Derrida put it, “is not, we repeat, a question of the past. It is not the question of a concept dealing with the past that might already be at our disposal or not at our disposal, an archivable concept of the archive. It is a question of the future, the question of the future itself, the question of a response, a promise and of a responsibility for tomorrow” (Derrida 1996, 27). A response to racism today that is responsible for tomorrow, would need to grasp racism and its hold on our society, not as a series of deplorable events that can be archived, contained or properly restrained by history for all prosperity. Racism as we have too long observed is inevitably produced, contemporaneously, in time, through ongoing processes, practices, and everyday interactions (reaching in and out of the past) that we participate in wittingly and unwittingly. The question of the future of racism in our country, and the promise of it disruption, limitation, and ultimate elimination is, therefore, not to be found by searching somewhere “out there” but hauntingly “in here,” in lived (and living) experiences well within our reach, where the responsibility for tomorrow rest.

As we reflect on the allegorical substance of the myth of the Gordian knot, we might do well to recall that according to the story “anyone who could unravel the elaborate knot,” a knot tied so tightly, so completely that it was impossible to see how it was fastened “was destined to become ruler.” As a nation and a people, we have wrestled with racism, our Gordian knot, for far too long and if we are to solve it, to become rulers of our own destiny, in our time, which comes successively to each of us in our turn, the time for wrestling is over. Before the light of this day fades we must find, within ourselves that greatness that the story tells, Alexander possessed when he purportedly cut the Gordian knot with a power that lay, not in might or sword, but in foresight and courage, the wisdom and will, to know and do, at every point, what is uniquely and collectively required of each of us.

As a discipline, our tools for documenting and analyzing racism may be unparalleled, but if we wish to undo it, to end racism now, each time, and for all time, it may require an undisciplined and audacious surmise. Through art we are lifted, rallied, and reminded of that greatness within each of us, something that can get lost in the endless archive and critiques. Reminded that through our lives, interactions, and even love, we can in fact undo the means and ends of racism before they capture and cripple another generation. But the desire alone cannot end racism, it must be informed, focused, and renewed. Through social science we may be uniquely enabled and prepared, in the words of the poet Wallace Stevens, however difficult it may be, to “see the very thing and nothing else, see it with the hottest fire of sight” and only then might we “burn everything not part of it to ash” (Stevens 1947) and commit it to past, though never to forgetfulness. Through our shared moments of everyday intentional victories over racism, within our reach, and multiplied in the lives of millions across this land, we can all be lifted by a great tide of justice, equality, and inclusion, working together, however imperfectly, ever towards that more perfect union.

T.S. Harvey is associate professor of medical and linguistic anthropology at Vanderbilt University.

Cite as: Harvey, T.S. 2019. “The Gordian Knot of Racism, Explorations in Incidental Anthropology.” Anthropology News website, March 5, 2019. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1107