Article begins

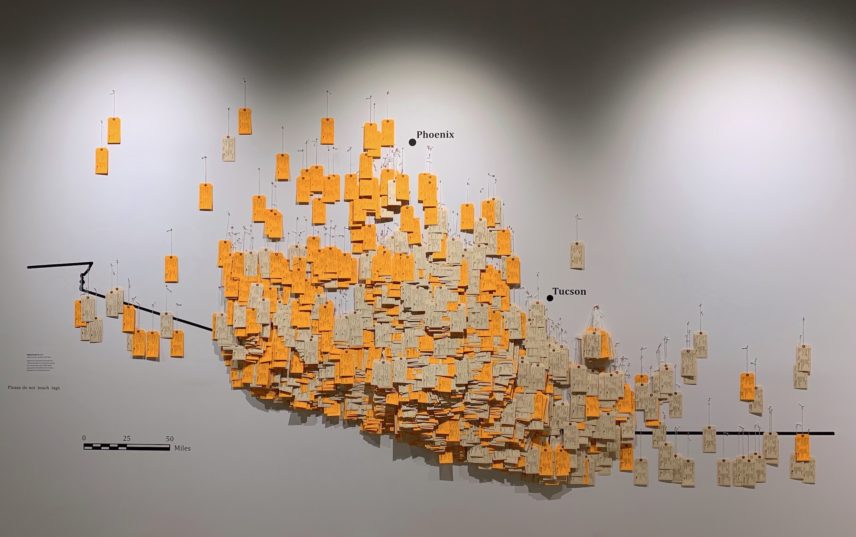

Hostile Terrain 94 (HT94) is a global participatory art exhibition created and organized by the Undocumented Migration Project (UMP), a Los Angeles-based nonprofit research, arts, and education collective focused on documenting and raising awareness about clandestine migration issues around the world. Using a public database made accessible by the humanitarian group Humane Borders in partnership with the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner in Arizona, HT94 coordinates thousands of volunteers to install large wall maps of the Arizona–Mexico border to visually represent the more than 3,200 people who have died crossing the Sonoran Desert since the mid-1990s. We are currently partnered with nearly 130 hosting institutions and organizations across six continents who will be mobilizing their local communities to assemble their own unique versions of the exhibition between 2020 and 2021.

| ML Number | Name | Sex | Age | Reporting Date | Surface Management |

| 01-00697 | Unidentified | Male | Unknown | 2001-05-01 | Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner |

| 01-00748 | Cruz-Mendoza-Cruz, Fernando | Male | 31 | 2001-05-09 | Tohono O’odham Nation |

| 01-00791 | Sotelo-Mendoza, Alicia Adela | Female | 46 | 2001-05-17 | Tohono O’odham Nation |

| 01-00823 | Sanchez-Najera, Felipe | Male | 53 | 2001-05-23 | Private |

| 01-00861 | Unidentified | Female | Unknown | 2001-05-29 | Tohono O’odham Nation |

Forensic data for individuals recovered from the Sonoran Desert (Humane Borders 2020).

Participants engage with and create the exhibit by writing out the names and forensic information for each of the thousands of people known to have died while crossing the border. These tags are mounted onto a large map of the border between Mexico and Arizona in the exact location where human remains were recovered. Manila tags represent people who have been identified and orange tags are used for unidentified human remains. The goal of this exhibition is to memorialize these lost lives, while also educating the public about the United States’ inhumane border enforcement policies.

Dangerous ground

In 1994, the United States Border Patrol formally implemented the immigration enforcement strategy known as “Prevention Through Deterrence” (PTD). This was a policy designed to discourage undocumented migrants from crossing the United States–Mexico border near urban ports of entry. Closing off these historically frequented crossing points funneled people toward more remote and depopulated regions where the natural environment could act as a deterrent to clandestine movement. Policymakers anticipated that the difficulties people would experience while traversing dozens of miles across what the Border Patrol called the “hostile terrain” of places such as the Sonoran Desert in Arizona would ultimately discourage migrants from attempting the journey. This strategy failed to deter border crossers, and more than six million people have tried to migrate through the Sonoran Desert of Southern Arizona since the mid-1990s. At least 3,200 people have died, largely from dehydration and hyperthermia, while attempting a crossing. Forensic research conducted by the UMP suggests that desert environmental conditions often destroy bodies before they can be recovered, making this statistic a likely underestimate of the actual number of fatalities (see Beck et al. 2014; Martinez et al. 2014). In recent years, this policy has shifted people toward Texas, where hundreds (if not thousands) have perished while attempting to cross the border. PTD is still the primary border enforcement strategy being used along the United States–Mexico border today.

Translating anthropological data

Inside the Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College, students get changed for their modern dance class. Ten feet away, I (Gabriel Canter) sit at a makeshift table in a room where the first class is finishing up their routine, the wall vibrating to the pop music’s rhythm. On that same wall, toe tags hang above my head as I fill out a blank card with the death details of Gabriel Torres-Alcala. Age: 47; Cause of Death: Unknown; Body Condition: Decomposed; Reporting Date: May 1, 2003. He shares my name, and his body was found on a day that I remember from my childhood. I sit there thinking of what I was doing that day, guessing what Gabriel Torres-Alcala’s last moments of life may have been like and how he ended up dead in the desert.

Gabriel’s experience at Bard College highlights the tensions that can arise when anthropologically driven projects such as HT94 both transcend conventional disciplinary boundaries and find homes in diverse and sometimes unexpected spaces. At its basic level, HT94 is a crowd sourced data visualization project that asks participants (i.e., those filling out tags) to bear witness to the human cost of clandestine migration. Meticulously placing toe tags in the exact location where bodies were found is not an aesthetic decision, but rather a deeply felt moral responsibility to accurately memorialize and honor the dead. By translating forensic data (represented in an Excel spreadsheet) into a handwritten and hand-built visual form, the project seeks to forge connections between those who died in the past and those who wish to raise awareness about this tragedy today.

The encounters this exhibition has had with the arts has inspired new forms of making, visualizing, and producing anthropological work (Rikou and Yalouri 2018). It has also led to ongoing conversations about disciplinary boundaries and the nomenclature we should use for describing our practice and our roles (see Morphy and Banks 1997, 30). HT94 often occurs in art spaces, but we are reluctant to have it solely define its location. In many ways, we are attempting to disrupt the art space by installing a project that is deeply anthropological in its commitments but with an aesthetic that can sometimes be misinterpreted as simply the result of “artistic decisions.” This misinterpretation was exemplified during an HT94 installation when a gallery curator, growing frustrated with the time-consuming process of installing more than 3,200 tags in their exact locations, commented, “It doesn’t really matter where they go, does it? It’s just art.” Our counter to this comment was, “It does matter. This is not ‘just art.’ These are people’s lives tragically cut short by inhumane federal policies. We are committed to preserving the details and locations of these deaths as a form of witnessing.”

The friction that comes from ignoring disciplinary boundaries or rules is nothing new to the Undocumented Migration Project. For over a decade, the UMP has refused to be pigeonholed into one subdiscipline of anthropology while also drawing widely from the arts and humanities in an ongoing attempt to document and raise awareness about the experiences of people crossing borders. What we have found most frustrating during the last decade of work is the constant need to explain where exactly the UMP fits in regards to the social sciences or arts and humanities. These are often tiring conversations that we reluctantly participate in. We find that these navel gazing discussions can distract from the task at hand, which we believe is pushing the boundaries of what anthropology is and what can it can do to improve our understanding of the human experience. We need less discourse about what anthropology is and isn’t and more concrete examples of how we can translate our work for new publics in innovative and thought-provoking ways.

Collaboration and connections

The lives at the center of this humanitarian crisis are often obfuscated by numbers and dry policy briefings. It can be easy to get lost in the statistics of apprehension, deportation, and death. HT94 seeks to reshape some of this “data” into a form that makes more legible the fact that these numbers represent actual people. We envision the act of writing out the name and information of someone who died as a momentary way for our living participants to connect with them and this issue. The experience can be intensely emotional, particularly for those who may have personal connections to migration or who are able to draw parallels to their own lives.

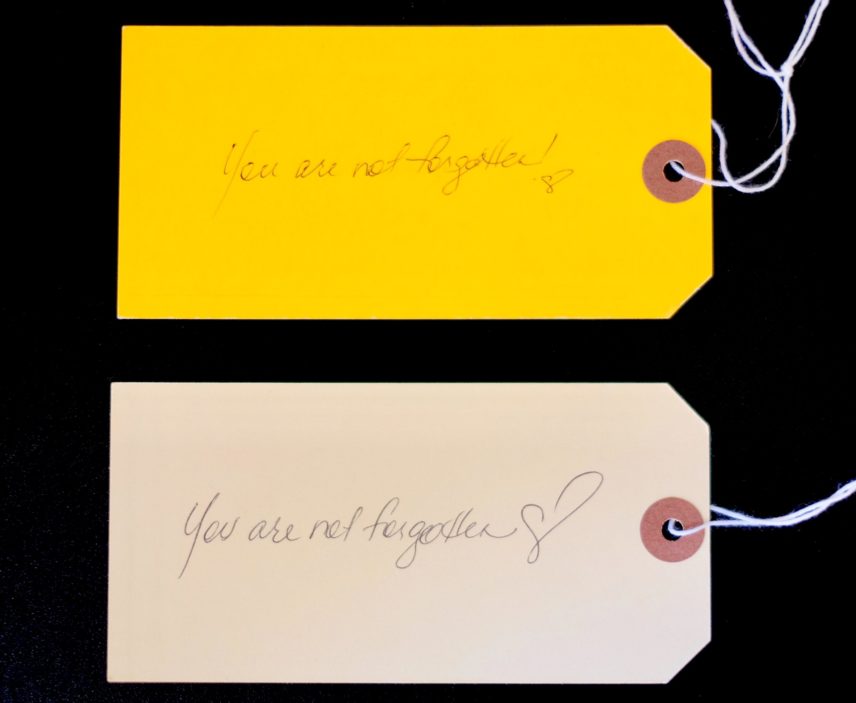

One volunteer at a prototype of HT94 at the Penn Museum in Philadelphia participated by filling out tags with her son. After her 30-minute session of writing out the names of the dead, she sat with us and cried over the tragedies she had witnessed through her pen. In those 30 minutes, she had written the death details for people who were the same age as her son or whose remains were found on days she spent celebrating. After walking away to take a moment to herself, she came back and spent several more hours memorializing many more who have died in the Sonoran Desert, writing “You are not forgotten” on the backs of each tag. Before leaving, she asked if she could take home the tag of the deceased boy who was the same age as her son so she could pray for him. For many volunteers that day, the exhibition brought something previously distant and unfathomable closer to home; the commonalities they found with the deceased connected them to the issue in unexpected ways.

A key element of HT94 also involves facilitating creative spaces and freedoms to explore dynamic forms of collaboration and information dissemination. To this end, we have encouraged our hosting partners to transform the exhibition within the context of their own local communities by creating complementary programming unique to each site. For example, in July 2020, the official launch of the exhibition occurred virtually in Santa Fe, New Mexico, which also included the display of photos (taken by Michael Wells) and drone video footage of the Sonoran Desert to illuminate the harsh landscape. All exhibitions will have access to an augmented reality experience developed by the UMP that will allow people to virtually tour the Arizona desert, view and listen to interviews with migrants and those who have lost loved ones in the desert, and interact with 3D replications of artifacts such as backpacks, water bottles, and personal possessions that people have left behind while migrating. The augmented reality experience, along with storytelling workshops in certain locations, will provide a platform for individuals to voice their own personal narratives of migration.

As participants fill out tags and grapple with various emotional responses, some feel a desire to take action outside of the exhibition space. HT94, along with the additional programming of hosting partners, provides communities with opportunities to take action and advocate for positive social and political change. Many hosts are collaborating with local organizations to highlight the intricate ways that immigration is intertwined with other forms of systemic inequality that are all too present in our nation and encourage people to push for reform.

Hostile Terrain 94 is a social science project that seeks to actively, collaboratively, and reflexively explore issues of migrant death and its presentation and representation across many locales, communities, and countries. We hope that this evolving project will serve as a model for a type of publicly engaged anthropology that refuses to recognize the authority of disciplinary borders or be constrained by the expectations of particular spaces.