Article begins

This exercise in eliciting early memories describes childhood experiences that led me to become a Latin Americanist anthropologist. An early recognition of cultural diversity and an inkling of entire realms of human experience beyond the here and now may have been decisive motivational factors for my career path.

The Spanish missions in California serve as one example of my attraction to things Latin American while coming of age in Southern California. As far back as I remember, I enjoyed family car outings with occasional side trips to explore the mission sites. In elementary school, we were told that the padres converted the Indians to Christianity and taught them to farm, but we learned nothing about the territorial and cultural dispossession or the decimation of their populations through disease, forced labor, and direct attacks. I chose the Santa Barbara mission to draw for a combined art and social studies unit because we had visited the beautifully restored buildings and grounds. The mission aesthetic, encompassing its contemporary applications as a regional decorative style, influenced my initial choice of architecture as a college major. Only recently have changes in state curriculum guidelines replaced California mission art projects with fuller accounts of accomplishments and survival struggles of the state’s First Nations.

Such patterns of sensory experiences and social encounters became matters of critical analysis, occasional disillusionment, and quests for expansive alternative life choices in my transition from childhood to youth. I have assembled some of these foundational memories into provisional accounts of the activities of families, neighbors, and other reference groups in those past scenarios, thereby contributing to autoethnohistory―biography, history, ethnography―as a hybrid genre. I urge others to ponder the formative observations and encounters that attracted them to anthropology. In this way, we will be able to compare our expanding and shifting perspectives through the years for fuller understandings of our personal and public lives today. As anthropologists, might we thereby reconcile to some extent our differences of temperament, positioning, and purpose as reflected in divisions in the societies around us?

For me, early yearnings to overcome confusion about the prevailing cultural milieu initiated what eventually became a compelling need to study anthropology. My parents were German-Jewish refugees who arrived in the United States in 1939 and moved with me to Los Angeles shortly after I was born in 1943. Their efforts to cope with loss and displacement and to adopt a Southern California lifestyle contributed to my cognitive dissonance. They continued to speak German, while participating in a quasi-community reconstituted by a wider range of Central European immigrants dispersed throughout the city. I felt like an outsider growing up, attempting to master appropriate norms and routines in my interactions with playmates and schoolmates. Emerging from my lunchbox, for instance, the rye-bread sandwiches with German sausage and brown mustard stood apart from all the white-bread sandwiches filled with baloney and yellow mustard or peanut butter and jelly.

Among my earliest memories, dating from 1946 when I was three years old, my mother and I walked a couple of blocks from our hillside basement apartment to board a bus at the intersection of Slauson and La Brea Avenues. The route traversed a swath of the Los Angeles sprawl to my pediatrician’s office at the iconic corner of Hollywood and Vine. Like my parents, she was a German-Jewish refugee who, as I later learned, attended to many other Central European immigrants’ children. I was afraid that this kindly lady would give me a shot, but excitement about the bus ride remains vivid, and seeing the world felt worth that danger.

The route along La Brea Avenue crossed many other streets with names that were catchy sounds but only became meaningful over the coming years: Jefferson, Adams, Washington, Venice, Pico (the last Mexican governor of Alta California), and San Vicente. At that time, I associated the names with their distinctive streetlights: among others, the simple lamps looming on arching poles along Olympic Boulevard, the glass boxes with ornate metal frames on Wilshire Boulevard, and the spiky metal frames covering the lamps on Sunset Boulevard.

La Brea Avenue passed within a few blocks of the La Brea Tar Pits, an eerie pond filled with a thick black substance that slowly formed large bubbles. My first memories of the site are sensory, not yet associated with its importance in yielding fossil evidence of extinct species (mammoths, giant sloths, saber-toothed felines, among others) and artifacts left by ancient human populations. I had no idea of the significance of the fascinating goo, used as an adhesive by human groups in previous centuries or its current relation to the ubiquitous derricks around town pumping petroleum. At some point, possibly when beginning to study Spanish in the ninth grade, I found out with a sense of betrayal that brea translated as tar. In Anglophone Los Angeles, I never heard anyone complain about the redundancy of the La Brea Tar Pits (“the tar tar pits”). One of my disappointments with an otherwise reasonably good public-school education was an inability to converse in Spanish after five semesters of coursework.

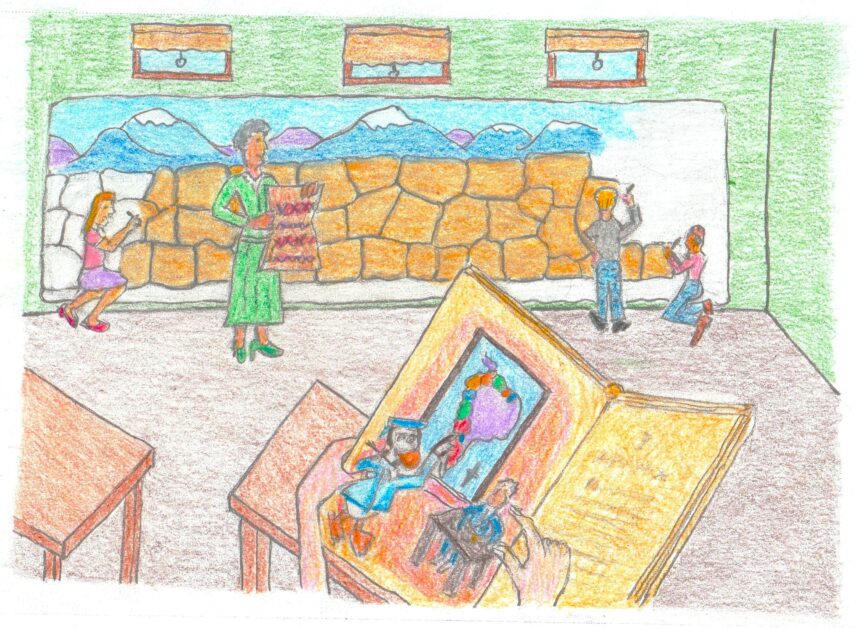

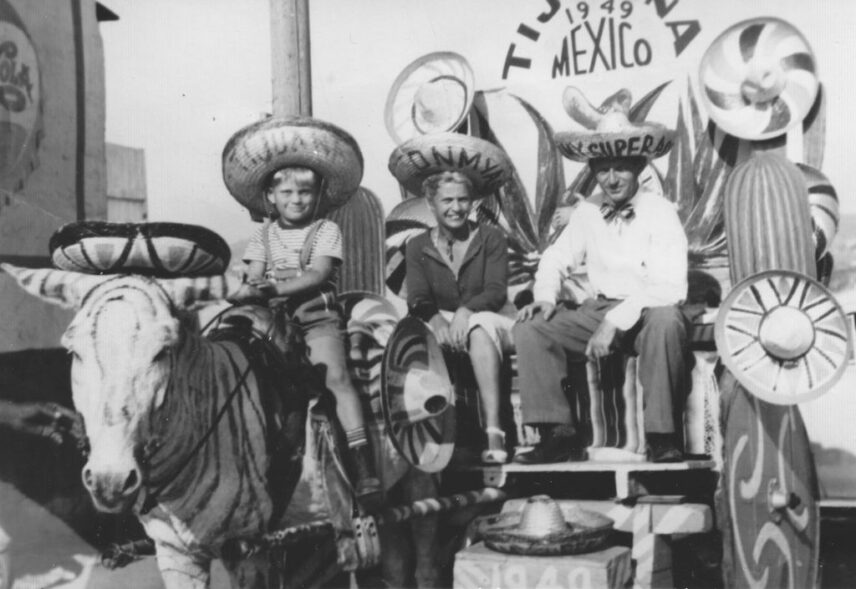

Imperceptibly then―but possible to re-create in stages now―I developed an intense curiosity about the Latin American region that extended to my hometown. In the third grade, our class prepared an Inca pageant for a PTA (Parent Teacher Association) meeting. We painted murals with massive, intricately fitted stones and stitched iconographic designs on burlap tunics―whether authentic or not I cannot now envision. Among the piles of books I brought home from the library for summer reading, one of my favorites was Donald Duck Sees South America (H. Marion Palmer and the Walt Disney Studio, 1945). Despite the Disneyfication, the appealing drawings and informative text reinforced a nascent fascination with the Andean countries.

Meanwhile, I passed many pleasant days playing with a Chicano neighbor across the street. I listened to him converse in Spanish with his abuelita, who had not learned to speak English. He had older brothers who dressed “sharp” and “customized” their cars with fancy paint jobs and upholstery. He could call on them when other boys bullied him. In seemingly inevitable boyhood squabbles, I got into fights with one Chicano schoolmate who called me a teacher’s pet and a kid in the next block who called me a “dirty Jew.” In the latter conflict, before we came to blows, more words were exchanged: “Oh yeah, what are you?” “A Mormon.” “Well, you’re a dirty Mormon.” Of course, neither of us understood the group identities and animosities behind these labels. Some fights created lasting enmities; others generated mutual respect, leading to friendships of sorts.

In addition to the few families who could claim Indigenous descent and the many Mexicans present before California became a state in 1850, the rapid population growth of Los Angeles in the first half of the twentieth century brought more migrants from south of the border, as well as from Midwestern and Eastern states and from more distant countries in Europe and Asia. Ethnic differences notwithstanding, we all were proud when Richie Valens, a Chicano student from a neighboring high school, became a rock idol with the crossover hit “La Bamba.” We mourned together when he died in a plane crash in 1959 at the age of seventeen, flying between concert venues. We shared a broader Angelino identity, many of us striving for a California cool demeanor, and I recall feelings of envy of the Chicano kids for their style and what I now recognize as having local roots I lacked.

When I ponder reactions these many decades later, I feel quite certain that my difficulties in bridging the gulf between my parents’ subculture and the mosaic of other subcultures, ethnic and otherwise, had much to do with the welling desire to learn how to function in Latin American contexts. At the time, I rejected almost everything German and Jewish in a sometimes desperate struggle to be more like my peers in the emerging suburban youth subculture. I remain mystified about a turnaround, as soon as I started college, deciding to study my own heritage. I took courses in German language, literature, and history, along with a year at the University of Göttingen under the auspices of a new University of California study abroad program. The immersion inspired and empowered me to consider living and working beyond Euro-American frontiers. After graduating with a field major in the social sciences, I served two years as a Peace Corps volunteer in Thailand. Only then, with a brief detour through public health, did I find a lifelong path by turning to anthropology and specializing in Latin America. The choice of Bolivian Quechua coca cultivators for dissertation research resulted from a combination of predispositions, circumstances, and decisions with causes and consequences discernable only in retrospect.

* * *

Autoethnohistory need not be a vanity project. I have taken the opportunity to portray an ethnographic niche in the kaleidoscopic mosaic of my hometown’s past. This may help colleagues appreciate where I am coming from in my personal as well as professional approach to anthropology. Accounts of college experiences, graduate training, and successive career stages also offer valuable ethnographic insights about past times and places, ultimately unique for each of us in their details. Our developing selves serve as witnesses arriving at a range of standpoints as varied as the diversity within the population of anthropologists. If we are going to continue to interact with mutual respect, given the increasingly divisive conditions under which we live and work, discussion of formative influences serves at least two purposes beyond enrichment of the ethnohistorical record. We can recognize potential sources of bias in everyone’s perspective―including our own―while also celebrating points of view, based on distinctive positionings and experiences, as sources of expertise and commitment.