Article begins

Imagine […] an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception. How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of “Green”?

—Stan Brakhage, Metaphors on Vision

Engaging the terrain between the disciplinary boundaries of anthropology and painting in this essay, I argue for the importance of nurturing a reflexive act of seeing. As an undergraduate student in anthropology, I was taught the importance of rigor in the gathering of data through participant observation, and therefore contemplation, exploration, and open-mindedness were imperatives. I was taught that how we observe has consequences, from what kind of questions we pose to what we see and the analysis we derive from our observations. However, I was not offered techniques to develop a reflexive practice in relation to observation. I found this possibility in the arts.

I suggest that since both anthropology and painting use visual reading skills to gather and represent findings, anthropologists can gain methodological insights from the ways painters might train their visual skills to understand and apprehend the world and their own place in it. I learned to paint under the apprenticeship of an eminent Norwegian painter, Jan Valentin Saether (1944–2018). We met in 2004, and during my apprenticeship with him I became gradually aware of ways of seeing that I was not used to. He introduced me to the method “seeing without an object,” which I understand not as a mere technique of painting, but as a mechanism to develop a more deeply reflexive approach.

Seeing without an object

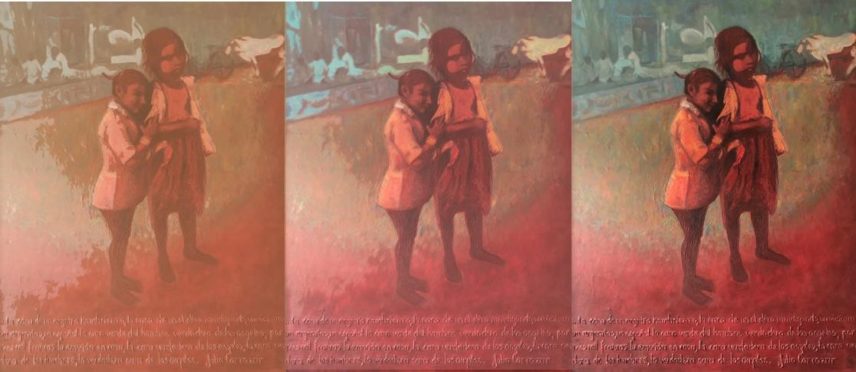

Saether applied this method in his teaching on how to master painting skills and explore the personal artistic vision. Through this method, the apprentice learns to construct the image she wishes to produce by the mapping of relations between light and shadow. By mapping what he called “collisions and transitions,” the image is the result of a process that moves away from a mechanical reproduction of bounded forms known a priori, such as a hand, a nose, a body. In this way, the image is understood as an entity that emerges through the reproduction of different values that light and shadow create on the surface. The method attempts to redirect the view to focus less on the visual experience than on its performative dimension, that is, to the patterns of light and shadows. This move away from focusing on deciphering objects allows for particular attention to the quality and dimension of the interstices, the spaces in between that the shadow and light create. The guiding question of the work is then not what it is, but how it is.

Seeing without an object does not necessarily imply indeterminacy, although the moment of nonrecognition of comprehensible forms can be part of the process. The mapping of light and shadow takes place by adding a succession of colored layers that gradually overlap. The structure of the image is established at the beginning of the work, but complexity is progressively added to it. The first layer on the painting consists of a monochromatic completed version of the painting where the tonal range and value are simplified to three colors: the light tone of an earth color (in my case raw umber), a mid-tone, and a dark tone. Through the consecutive layers, the painter still has to map the light and shadowy zones monochromatically, but in greater detail, now using intermediate variations between the darkest tone and the lighter one. When the mapping is completed, one gradually adds color to the monochromatic tones.

Thinking without a concept

I gradually discovered that “seeing without an object” offered me a possibility to put in practice what I had learned in anthropology about the importance of consciously striving to get rid of preconceptions, being more attentive to the gestalt, and how the whole picture with its details will only emerge from the background over time. The researcher cannot not rush assuming the form of the phenomena she studies. As the philosopher Emmanuel Alloa (2010) cautions, seeing something is not necessarily seeing something as something specific. We need time to recognize the phenomenon; any concept once named starts functioning as an object, which in turn delimits our exploration. Thus, sharpening our observational skills deeply shapes our way of knowing and thinking. It is in this sense that I translate “seeing without an object” to “thinking without a concept” in my ethnographic practice. This means exploring the field of research and later the data gathered without fixing the point of reference to a concept and an assumed meaning. If I translate the steps from my painting practice into my ethnographic practice, it will mean that in the field I will map relations that eventually will show me the relevant phenomenon to be analyzed in greater detail at a later stage. During writing and analysis, I will delay identification of the object of inquiry by exploring “the spaces in between”: the relations that make that object, in tandem with the interrogation of my way of knowing and my ethnographic point of view.

The guiding question of the work is then not what it is, but how it is.

In recent decades, anthropologists have increasingly searched for approaches that challenge the discipline’s foundational epistemological understandings, and for novel modes of knowing, whether through the so-called material, ontological, and decolonial turns or through other critiques. Anthropologists applying these perspectives have called on us all to develop greater sensibility, to be able to discover other ways of conceptualizing and enacting in the world or worlds. My reflections on my artistic practice come from my engagement with these approaches. I am not suggesting that there exists a single technique; from time to time, each researcher may find their own way to train their skills of perception. This might be through painting, drawing, or creative writing, while others might enter the process by being more playful with concepts. In Philosophical Investigations ([1958] 2001) Wittgenstein presents the reader with concepts and words from different points of view simultaneously in an attempt to change their way of looking at things. According to him, discoveries in philosophy are in reality discoveries of new ways of seeing: “What you have primarily discovered is a new way of looking at things” (ibid., 61).

I am an anthropologist who is also a painter interested in challenging her common ways of seeing as well as in reflecting on the hows of her ethnographic practice. How we see and what we see, indeed influence what we know. Nevertheless, our visual practices are highly influenced by what we already know, so the reciprocal relationship between seeing and knowing is in reality a hierarchical one. Once we have learned and internalized ways of knowing, it is not easy to challenge and reshape our ways of seeing and thinking otherwise. It is in this sense that I am intrigued by how “seeing without and object” can challenge internalized ways of knowing and enrich the anthropological practice. Developing awareness of the act of seeing will in turn awaken awareness of the politics of seeing and knowing that influence the process of scientific knowledge production, challenging dominant understandings of the world and opening the way for other ways of seeing-knowing.