Article begins

Trucks stop

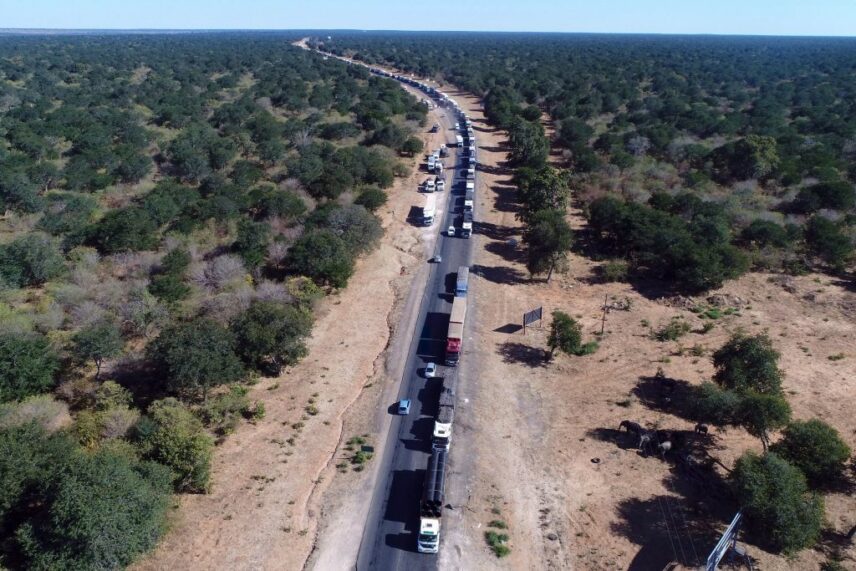

The line of long-haul trucks seems endless, stretching several miles from the South African border; a few engines idle but most are switched off in the effort to conserve fuel and are tacit recognition that no one will be crossing anytime soon. The air is hot and dusty. It is September 2020, and medical workers in hazmat suits make their way down the line of trucks, swabbing throats and noses, distributing masks, and checking cargo. Frustrations are running high, as the usual backups along the Tlokweng border have been exacerbated by confusing COVID-19 protocols and delays that put drivers in precarious positions, weighing personal health and safety with the need to deliver freight across the region.

Ernest Bongaka is a 35-year-old long-haul trucker who has been driving for almost 10 years but who has never encountered anything like the traffic backup along the border. He works for a large local company, headquartered outside of Gaborone, Botswana, and transports everything from building materials to perishable goods, traveling across multiple borders several times each week. Ernest and his friend Macdonald, who drives for a different company based in Gauteng, South Africa, grew up together in the small village of Malolwane along the border of the two countries. Fascinated by engines and trucks of all sorts, the friends became certified drivers and worked locally in Botswana for a beverage distribution company in Gaborone before finding jobs in the international long-haul industry. As Ernest shares via text as they sit in the same, seemingly interminable line of trucks that day, “The border control think we are all carrying COVID, they don’t see the rest of the cargo, or the reasons we need to move, they just see us as sick.” Both Ernest and Macdonald have been accused of being vectors of the virus, border officers and even their family members shouting suspicions and sharing concerns that truckers were and are still spreading disease across the continent, fears of COVID-19 mapped onto the drivers themselves.

In many ways the concern was warranted: cross-border traffic and travelers were significant factors in COVID-19 transmission throughout Africa and in particular along borders in the eastern and southern regions. In Kenya and Uganda, along with Botswana and Zimbabwe, truckers tested positive at rates much higher than those in the general populations (though lack of access to regular testing may explain some of those data) and were characterized in the news and conversation as literal carriers of the pandemic. International borders were closed or tightly restricted. Fear led some to close before any cases had been reported.

Although early in the pandemic, conditions varied across the continent, initial reports on social media suggested some real barriers to movement―as Ernest described, “One day, Tlokweng was at a standstill, nobody moved, it was like we were statues. On my regular route I would go through there many times, at least once a day, they knew me there, but then, full stop. That border would close for a day, close with no warning, with nobody telling us anything.” Prior to the pandemic, some trucking companies in the region advertised that with their own in-house clearing operations and bonded transfer agents, drivers and clients would easily move through customs without facing delays, VAT, or unexpected fees. As Ernest told me, “If you work for one of those companies you get a nice cab and an easy haul, things would be pretty seamless, no penalties for anyone, they weren’t stuck hanging around Beitbridge or Kazungula [border posts with notoriously long lines for truckers and tourists alike]…but after COVID, everyone became the same…all of the drivers, all of the trucks, nobody moved.”

Ernest doesn’t use the phone to actually make calls; like many in the continent, he uses SMS, TikTok, or Twitter to communicate.

Other barriers to movement were even more profound. Macdonald and Ernest both described days-long quarantine periods while awaiting test results and without sufficient running water, toilets, or adequate space to socially distance from other drivers, adding to the public health crisis. As Ernest says, “It was so ironic, we were treated like we were carrying the disease and yet they had no ways to keep anyone safe; we had to figure it out ourselves, take it into our own hands to stay healthy.” According to the SA Long-distance Truckers Facebook page in May 2020, trucks were queued for nine days or more and “[P]olice…escorted trucks into Lusaka and parked off…[a]ll the drivers were loaded into a bus and taken to a university building and left there under heavy police guard to quarantine in inhumane conditions.” This despite drivers not showing any symptoms of the virus. Trucks were also not allowed to offload for that fear of “carrying COVID.”

The vilification is reinforced in varied national testing and contact-tracing policies. For instance, instead of general community testing, Botswana implemented a “sentinel testing” strategy, with a focus on points of transit, villages close to its borders, and points of entry, meaning that truckers and other migrants were tested most routinely. Tswana officials also implemented a color-coded permit system where holders could only cross into certain geographic zones during certain times a day to keep contact and the coronavirus at bay. Eventually, and similar to reports of what was happening in eastern Africa, Ernest and Macdonald began to follow posts online offering drivers negative COVID test results for sale, bribes to bypass the restrictions, lengthy interviews at customs, decontamination processes, and temperature and vaccination checks that were disrupting the flow of goods as well as individual driver paychecks.

TikTok

Even with COVID restrictions in place, informal cross-border trading activities continue, and people communicate. Borders are porous along these transportation corridors and images such as those of financially strapped Zimbabweans crossing the Limpopo River near the Beit Bridge border post into South Africa, exchanging cigarettes and beer for groceries and other household items with Musina residents, were shared widely on social media. For Ernest and the other truckers, these images sparked wide debate and their own social media (mostly Twitter and TikTok) discourse. For them, these informal crossings (framed as “illegal” by law enforcement officials) fed into the continued, problematic, and growing narrative that anybody crossing the borders, including truckers, were dangerous COVID-laden criminals. As Ernest says, “We had to do something, that’s not an image we wanted to persist, not of being criminals and not the idea that people couldn’t get what they need; the whole reason behind driving is to help people survive, to bring their goods.” Truckers often frame what they do on the road―their jobs―as a responsibility to protect others. For example, bokangbokang935, a South African trucking industry TikTokker, posts often about the need for truckers to help track down and even punish thieves who steal cargo off flatbeds.

Since its launch, TikTok’s popularity has grown rapidly across Africa. In October 2018, it was the most-downloaded photo or video app and currently has over 500 million monthly active global users. In Botswana, the number of people using social media for daily news doubled in the years just prior to the pandemic, from 2014 to 2019 over a third of the population gained access to those news sources. And throughout the continent, TikTok’s popularity and usage grew exponentially during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic and continues to grow.

Truckers claim this technology as something of their own. Ernest and Macdonald and many other truckers on social media leveraged their own growing social networks (once the purview of CB radios, most drivers now communicate and share information on social media platforms) to speak up against unfair treatment at the borders and in the process, created a more effective distribution system of essentials, COVID information, personal protective equipment, food, and water. As Macdonald proudly describes, “We are the essential workers now, we can move, even its difficult, we can move when everyone else has to sit still. We tell other drivers what load we’re carrying, what extras we can take and where it all needs to be. So if I know I have a free pallet and can take water, cans, and masks that are meant for Polokwane but might be held up back in Pretoria, then I will, all I have to do is post something on #southafricatruckdrivers and things will move.”

During the first year of COVID, when personal protective equipment was hard to find, when supply chains stalled and even simple masks were limited or nonexistent, particularly in remote areas, Ernest made certain that boxes of sanitizer, hand wipes, and soap were included in his load. In Francistown, Botswana, along the eastern corridor of the country and a highly trafficked route for transport throughout the entire region, much of the local population were without reliable boreholes or plumbing and using “tippy taps” instead. Made by attaching a jerry can of water to a stick, dowel, or branch and operated by a foot pedal connected by a rope, tippy taps are ways that even those without running water could increase handwashing and contactless cleaning. But in Francistown and villages outside of Dukwi, near the border, it became clear that cans, soap, and twine were in high demand and low supply. Ernest and two of his colleagues brought a load of cans (there are often excess jerry cans in Gaborone or NGO headquarters, as they are seen as an essential yet easily donatable item), Sunlight soap, and rope to the community. As Ernest describes it,

We got the idea from those local guys on motorbikes, kids really, who were selling drinks, cigarettes, snacks…they’d bring you takeaways, any kind of food, seswa, pap, biltong or chocolate, sometimes beer, and definitely Fanta while you were in the border queue…they were weaving in and out of the trucks as we were lined up, delivering it all since we couldn’t move. You could yell to them to stop if you needed something, but mostly they began to just deliver things to people from online…nobody wanted to be face to face then anyway…so, TikTok, Insta, WhatsApp if you were in a group, the motorbike delivery guys would get your message and find you in the queue…sure they made money but it was the idea, that they had organized all this to help bring us things when we were stuck…we liked that and so did the same on a bigger, international scale.

In this way, the rise of TikTok as a traveler’s or trucker’s aid is a necessary means through which communities of care, safety, and supplies continue to travel even as physical cross-border movement grinds to a veritable halt. Technologies such as this are familiar as social movements and political organization (from the 2011 Arab Spring to Kenyan artisans entering a global economy using iPhones) are facilitated through such tools. Mobile phones are essential, and it is not surprising that the uptake of social media and mobile apps have been so tremendous in Africa. In Botswana, landline technology has been quickly outdated, eclipsed a decade ago by mobile phone usage. As Ernest reminds me, “If I didn’t have my phone, I wouldn’t have family, nobody would have food, and I’d be lost [laughs] literally…” The “family” he refers to are mainly other truckers and people on the road with whom he connects with along the way each week (girlfriends, friends, business partners). Ernest doesn’t use the phone to actually make calls; like many in the continent, he uses SMS, TikTok, or Twitter to communicate.

With their physical mobility restricted, drivers use other hashtags such as #truck_driver_south_africa, #truckersofsouthafrica, #africantruckdrivers, among others, as ways to update people on their well-being, travel status, and road and border closures. Truckers and their communities create social networks of care and encouragement and even help one another combat disease through sharing resources and bringing them to hard-to-reach communities. Where once truckers used CB radios to connect, they now deploy TikTok to broadly (and visually) share experiences and information, voice opinions, and film the impact of the pandemic on personal and professional lives.

The Last Mile

In a region where HIV/AIDS has been part and parcel of everyday life for generations, there are roadmaps for how to protect communities through behavioral change. Donor agencies and governments have long strategized how to best disseminate medicines and improve health literacy. HIV-awareness strategies are far from the early “ABC” (Abstain, Be faithful, and Condomize) campaigns of the Bush era and recognize the role of gender and sexual decision-making in negotiating perceptions of risk that surround health and illness. Edutainment strategies, such as the wildly popular Magkabaneng radio soap opera in Botswana, work well in addressing the impact of HIV in everyday life. Yet national, international, and NGO supply chains are fraught with challenges that continue to make the provision of medicine, care, and consistent messaging to people in their communities persistently difficult, a concept in global public health that is captured by the idea of going “the last mile.” In 2016, “Project Last Mile” (PLM) was rolled out by USAID in partnership with Coca-Cola, in the effort to draw on best practices in the private sector, coordinate community health efforts, and achieve medical access for all in Africa.

“We had to do something, that’s not an image we wanted to persist, not of being criminals and not the idea that people couldn’t get what they need, the whole reason behind driving is to help people survive, to bring their goods.”

The question driving the development of PLM remains, “If you can find a Coca-Cola product almost anywhere in Africa, why not life-saving medicines?” With the aim to leverage Coca-Cola’s best practices in providing products and creating “pick up points” for medications, their efforts have been successful. In 2021, COVID-19-specific efforts reached over 27 million people in South Africa in just five months through a mixed-media campaign about the importance of vaccinations. From September 2021 to January 2022, vaccination rates in South Africa increased from 10 percent to almost 30 percent, considerably greater than across the continent as a whole.

It appears that the informal, social media driven (and literally driven) goods and information that truckers in southern Africa are bringing to communities, mirrors much of what larger, international and ministry of health offices are trying to do. The strategies that truckers are using are fodder for those thinking about how to reach the millions of African populations without access to vaccines, PPE, or communication about COVID-19. For example, in early 2022, Director of External Communications for the South Africa Department of Health, Nombulelo Leburu, stressed the need to continue these efforts and shift the focus to “identify more innovative, nontraditional communications approaches to motivate vaccine uptake, especially among the youth.” Ernest is therefore understandably proud when he talks about how the USAID and Coca-Cola partners “had the same idea that we did” and describes the latest “viral” (he always puts it in air quotes) TikTok video about vaccine uptake, viewed over six million times in one month. Today, Project Last Mile is focused on exploring other strategies to motivate vaccinations and health precautions and improve awareness, mostly through incentives such as airtime for mobile phones, electricity, or cash vouchers. Ernest and Macdonald on the other hand, continue to carry COVID-related goods (tests, vaccines, medical equipment, PPE, sanitizer, wipes, and masks) alongside their regular loads. They are literally closing that gap, going that last mile so that others (local community members, NGOs, volunteers, practitioners, and others) may not have to.

With the Africa CDC efforts to enact “digital disease surveillance,” truckers like Ernest and Macdonald find themselves somewhat unintentionally at the forefront of innovative global public health interventions. The CDC site describes their next efforts as the “aggregation and analysis of data available on the internet, such as search engines, social media and mobile phones, and not directly associated with patient illnesses or medical encounters” but rather an approach to tracking behaviors and movements of people. There is clearly interest in developing digital surveillance strategies for public health actions worldwide, and arguably the informal networks and strategies of long-haul African truckers may again provide the best insights about how to create community, combat disease, and move essential consumer goods where they need to be.