Article begins

My maternal grandmother spent hours sitting on the narrow verandah outside her apartment. She waited patiently for the breeze, a respite from the extreme heat of the Chennai summer. There were days when you could catch a taste of sea salt in that breeze, carried a few kilometers from Besant Nagar Beach. As my grandmother grew less certain of her footing, the short walk down the stairs to the road began to resemble a daunting expedition. That narrow verandah allowed her to enjoy the breeze while bypassing the treacherous steps to the outside world. Around the time that my grandmother passed away from a combination of colon cancer and clinical disregard, a large concrete call center was erected in the lot facing the verandah. Her breeze was cut off.

Of course, not all breezes cool. The hot wind known as the Loo will, as Salman Rushdie put it, “melt the marrow out of your bones” (1983, 50). The causes of heat are multifarious: predictable seasonal changes; natural idiosyncrasy; failed or delayed monsoons; humidity. Heat is also, as we know well in our time of heightened discourse around climate change, anthropogenic. And in cities like Chennai, the heat has only gotten hotter. Carried along by the liberalization of the economy, Indian cities have experienced a dramatic metamorphosis over the last few decades. More cars, more roads, more businesses, and more people. Flyovers stretch above city streets drenched in traffic. Squat outsourcing centers colonize entire blocks. New housing developments arch into the sky, billboards out front promising an oasis in the middle of the city.

Yet, the middle of most Indian cities is less of an oasis and more what meteorologist Leonard O. Myrup called, back in 1969, an urban heat island. The city has been made anew with concrete and tar, materials that absorb and trap radiation in terrestrial form. Water reservoirs plummet, the city simmers. Airflow is rerouted and, finally, blocked by towering constructions at every turn. The heat cannot dissipate. The city’s dynamic system of thermoregulation has failed. It cannot sweat.

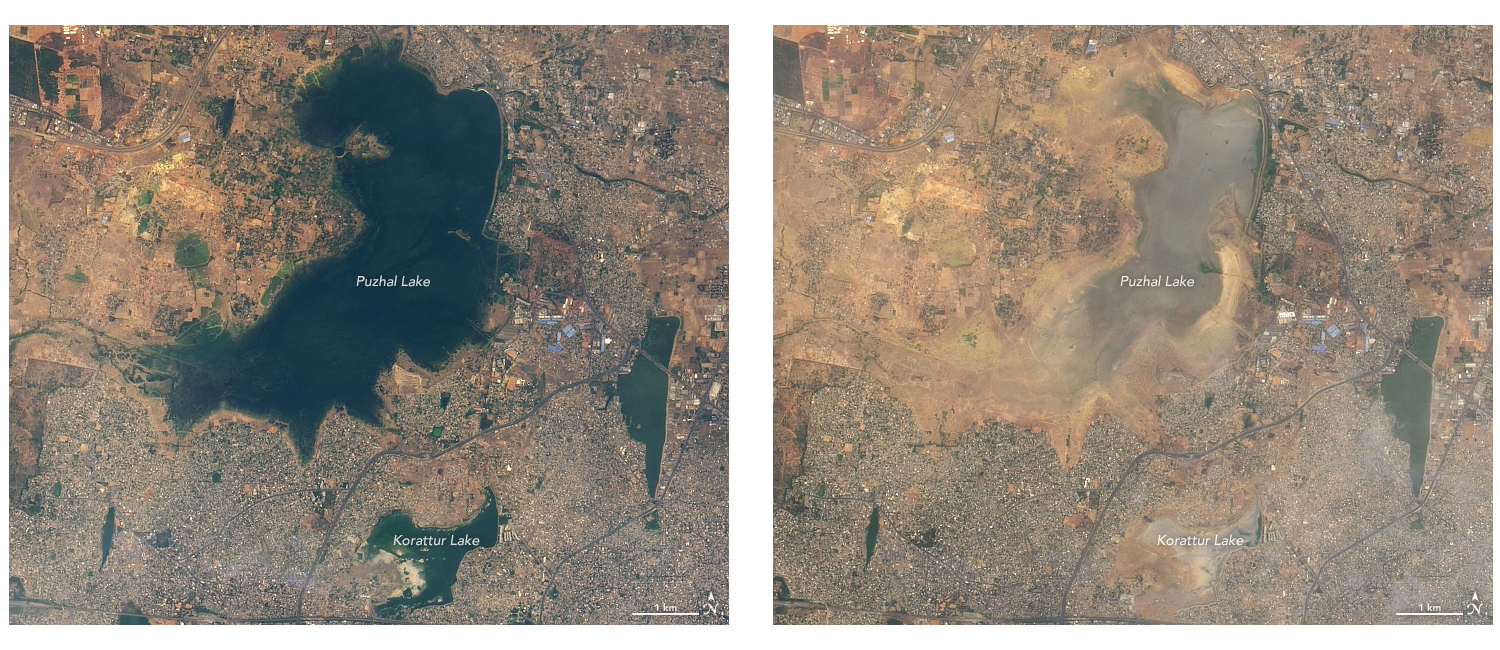

Images of Puzhal Lake, the main rain-fed reservoir in the state of Tamil Nadu, taken on May 31, 2018 (left) and, just a year later, on June 19, 2019 (right). NASA Landsat Image Gallery

My grandmother watched from her verandah as the city she knew changed, comforted by the breeze. Some years after she died, in the arid summer of 2015, temperatures across India soared to unexpected highs. In the southern part of the country, estimates indicate that nearly 3000 people and many thousands of domestic animals died as a result of this heatwave. The extreme heat also led to hyperthermia, stroke, heat exhaustion, severe dehydration, clotting, blood pressure fluctuations, and the aggravation of heart, kidney, lung and psychiatric conditions. Further heatwaves unfolded in 2016 and 2019. Stories of overburdened bodies were accompanied by stories of infrastructural collapse, as energy grids failed, over-taxed air conditioning units conked out, and asphalt roads began to melt.

These moments might seem exceptional, but they also form part of a history of heat which, with important exceptions, has scarcely been a subject of sustained analysis. This is especially ironic for anthropology. Since its transformation into a largely fieldwork-based discipline, anthropologists working in tropical zones have had to grapple with heat. Yet, more often than not, heat is taken to be the natural background; resisting heat, ignoring it, a mark of the fieldworker’s fortitude and cross-cultural poise.

What we might take from this is that heat in colonial-era ethnography was, above all, a nuisance.

When heat does make a furtive appearance in scholarly monographs, it is only to set the scene. For example, in his Argonauts of the Western Pacific, Bronislaw Malinowski mentions the “hot day” (2014, 36) when he stumbled upon a singularly picturesque village, or “the hot summer months” (2014, 235) that served as the docile background for the agential winds that defined the sailing patterns of Kula trading parties. For the ethnographer to mention the heat is to mark that they were there, but for the ethnographer not to dwell on that heat demonstrates an undoubtedly gendered kind of resilience, a ruggedness.

If we turn instead to Malinowski’s Diary, we find a rather different picture. “The frightful heat,” he writes, “is destroying me” (1989, 56). He details his “abhorrence of heat,” his “fear of encountering heat” (1989, 4). Heat, for Malinowski, was an unwelcome distraction, one that led to something like anxiety, irritation, and even lethargy: “In the daytime, the heat was such that I sweltered on the platform where I lay. The great part of Monday I sat on the platform doing almost nothing” (1989, 55). Heat was something you complained about in your diary, not something you theorized in your scholarship.

Where heat does emerge as an object of analysis, it is usually in the form of cultural elaboration: in the literature on South Asia, for example, the idea of innately hot foods as affecting one’s bodily constitution; hot brains as a descriptor for angry old people and sages; the heat released through menstruation; or the heat of unspent semen that can be converted to spiritual power (tapas) or dangerous lust (kama). Here, heat operates somewhere between literality and metaphor—a rageful, chaotic or libidinous heat that may or may not be hot to the touch.

What we might take from this is that heat in colonial-era ethnography (and even in contemporary anthropology, my own work included) was, above all, a nuisance. We might even say that heat was like colonialism: colonial rule interfered with social forms and customs; heat interfered with ethnographic practice. Both were epiphenomenal to culture. Although anthropology has long since taken up colonialism as a subject worthy of attention, heat remains curiously muted.

Power—in the form of electricity—operates as a buffer against environmental change and instability

As part of the archival research for my first book, a study of cures for tuberculosis, I found heat all over the record. While ethnographers pretended to ignore the heat, colonial-era physicians, administrators, and army officials did precisely the opposite. Heat was construed not only in terms of climate and geography, but also in terms of race. Heat was thought to make certain kinds of bodies more susceptible to tuberculosis, and to disease more generally. British soldiers who fell ill with tuberculosis were frequently sent home, their condition deemed incurable in the Indian heat. It’s no surprise then that heat was taken to be an impediment to any British aspiration of long-term settlement in India. Over generations, it was thought, British bodies might slowly transcend their racialized biologies to become acclimated to the tropical heat. But to do so was to risk going native.

Heat not only affected bodies but also technologies. In researching the history of diagnostics, I learned that the first use of the X-ray in India was likely during the military campaigns at the Northwest Frontier, in 1897, by British Surgeon-Major Walter Calverley Beevor. While the X-ray would prove invaluable on the battlefield, creating a device that was light enough to transport, sturdy enough to resist the elements, and simple enough to allow for makeshift repairs was a serious challenge. During Beevor’s train ride through central India up to the glistening cold mountains of the frontier, the insulating paraffin wax on his X-ray apparatus’ induction coils melted. Fortunately, he managed to repair the coils and wrap them in wet blankets to keep them cool.

For Beevor, heat demanded an improvisatory response. In India today, that response has become standardized and mass-produced. Take the air conditioner: available with a 2-star, 3-star, 4-star or even 5-star energy-efficiency rating, in both window and wall-mounted models. But ACs are expensive. In the state of Tamil Nadu, the erstwhile Chief Minister J. Jayalalitha provided small fans to her citizenry, each with her photograph of her affixed at the center, the axis around which the blades spin and the polity revolves.

Obviously, these technologies need power to run. Power—in the form of electricity—operates as a buffer against environmental change and instability, keeping fans and air conditioners running, making water potable, making the heat bearable. Yet, power production—from coal, oil, or other non-renewable sources—requires combustion, releasing particulate and hot air that further insulate life in the city. Moreover, an increased dependency on air conditioning contributed to widespread power outages for many during the heatwave of 2015, their salvation paradoxically deepening their crisis.

Even in less extreme times, power is not a given. Back in 2012, I remember the Chennai newspapers printing the schedule of power cuts, staggered across the city such that the swift-footed could move from one neighborhood to the next in pursuit of electricity. But these schedules were also misleading; the power disappeared for an additional hour here or there, or sometimes the entire night. Power fluctuations were normal. At those times, the air conditioner might make a heroic groan before conceding, leaving the sweltering ethnographer, like Malinowski, to sit “doing almost nothing.” Almost. Because doing almost nothing might, in fact, be the first step toward finally turning one’s attention to the heat, no longer as an obstacle to inquiry, but as something worth inquiring about.

Bharat Jayram Venkat is an assistant professor at UCLA’s Institute for Society & Genetics. His first book, At the Limits of Cure, is the winner of the Joseph W. Elder Prize in the Indian Social Sciences.

Please send your comments and ideas for SMA section news columns to contributing editors Dori Beeler ([email protected]) or Laura Meek ([email protected]).

Cite as: Venkat, Bharat Jayram. 2020. “Toward an Anthropology of Heat.” Anthropology News website, March 12, 2020. DOI: 10.1111/AN.1370